The revolution of July 1830 witnessed the first success for revolution and for the principles of popular sovereignty since the formation of the Holy Alliance fifteen years earlier. It gave rise to extravagant hopes among the mass of the people that at last an era of liberty and social justice had begun.

But the promise of the 'honeymoon period' was soon betrayed. As in July 1789, so in July 1830, the workers and lower middle classes of the Paris suburbs served only as assault troops for a revolution of the haute bourgeoisie. This time, too, they were robbed of the fruits of their struggle. Instigated by the liberal middle class, they had risen and expelled the hated Bourbons who had been imposed on them by the united monarchs of Europe in 1814. They hoped to set up a democratic republic. But when they met outside the Town Hall in Paris they found themselves confronted by a fait accompli. Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, and confidant of Thiers and Lafayette, had been proclaimed king.

The bourgeoisie, who had begun the revolution, had limited aims. Regal despotism; ruling 'by God's grace'; Catholic clericalism, the political power of which had increased to a frightening extent under Charles X; most of all, the rule of large landed property—these were the principal targets for attack. They were to be ended, but only to give place to the power of the bourgeoisie itself. Protected by a constitutional monarchy, it intended to keep power in its own hands. It had no wish for a democratic republic in which power would have to be shared with the petite bourgeoisie, workers and peasants.

This aim had now been achieved. The revolution of 1830 marked the completion of the bourgeois revolution which had begun in 1789. Tocqueville, the shrewd and penetrating observer of the period, wrote in his memoirs: 'In 1830 the triumph of the middle class had been definite and so thorough that all political power, every franchise, every prerogative, and the whole government was confined and, as it were, heaped up within the narrow limits of this one class, to the statutory exclusion of all beneath them and the actual exclusion of all above.'[1]

The middle class, now in complete possession of state power, was determined to assert its 'rights' against 'everything beneath it'. Through an electoral system based on property qualification, they precluded the petite bourgeoisie and working class from all influence over law-making. Because of the prohibition of trade unions and political associations, the workers were without the legal means of combining. Critics of the régime were effectively muzzled by Press restrictions. And when in November 1831, less than a year and a half after the July Revolution, the weavers of Lyon were driven by hunger to revolt—they earned about 90 centimes in wages for an eighteen-hour day worked in their homes—the government raised an army under the command of Marshal Soult to suppress them. Since every legal means of resistance had been taken away, opposition to the régime took the form of secret societies, of which a number soon appeared in Paris.

One of the secret organizations was the Society of the Outlaws, formed in Paris in 1834 by a group of German intellectuals and artisans. Two years later, a section under the leadership of Herman Ewerbeck and German Mäurer broke away and founded the Society of the Just, a forerunner of the International. The aim of the society was defined in Article 2 of its Statutes as 'the liberation of Germany from the yoke of an infamous oppression and the establishment of conditions which will, as far as humanly possible, prevent the return of misery and slavery'. Admission to the society was conditional on a solemn pledge that

we workers are at last tired of working for the idle, of suffering privations whilst others regale themselves in abundance. We want no further burdens placed on us by the self-seeking. We will no longer recognize laws which keep the most numerous and useful classes in conditions of humiliation, contempt and insecurity, so as to provide a few with the means of lording it over the working masses. We intend to become free and we wish for all men on earth the opportunity of living as freely as ourselves. No man will be deemed better or worse than his neighbour, but all will share equally in burdens, troubles, pleasures and enjoyment. This is what it means to live in a true community.

The Society of the Just had close links with the French revolutionary secret organization, the Society of the Seasons, led by Louis-Auguste Blanqui, Armand Barbès and Martin Bernard.[2]

Louis-Auguste Blanqui, who lived from 1805 to 1881, and who founded the Society of the Seasons, was one of the great revolutionary figures of working-class Socialism. He devoted his life selflessly to the cause, which he served without fear or compunction. He controlled his followers by his example, his intellectual gifts and his rigorous moral standards.[3] His father had been a Girondist member of the Convention and later, under Napoleon, a sous-préfet in Puget-Theniers, a small town at the foot of the Alps. At the age of seventeen, Blanqui underwent an experience decisive for his later career. While still a pupil at the Charles the Great High School, in La Rochelle, he witnessed the execution of four non-commissioned officers sentenced to death for their membership of the Carbonari. Blanqui swore to avenge the martyrs. He joined the Carbonari and fought on the barricades during the July Revolution, for which he was decorated by the government of Louis-Philippe. Strongly influenced by Buonarroti's history of the Conspiracy of the Equals, he developed the technique of the revolutionary coup d'état as a military art. This was the method by which, in Blanqui's theory, power would be captured and the 'dictatorship of the proletariat' established. Under the name of 'Blanquism' this theory became part of the history of Socialist thought.[4]

Blanqui was the inspiration of all uprisings in Paris from 1839 to the Commune in 1871. Sentenced to death after his first attempt at an armed coup; his sentence commuted to life imprisonment; freed by the revolution; soon afterwards sentenced to ten years' solitary confinement, and hardly free again; finally, a victim of his own fight for social justice—this was the rhythm of his life. Altogether he was inside prison walls for nearly thirty-seven years. He became a legendary figure to the workers of Paris, who called him l'enfermé—'the incarcerated'. Tocqueville, a member of the Constituent Assembly, saw him when on 15 May 1858 he stormed into the assembly hall of the Chamber at the head of a large crowd, to demand the government's intervention against Tsarist Russia on behalf of the Polish revolution. At the time Blanqui had been out of prison for hardly three months. 'He had wan, emaciated cheeks, white lips…a dirty pallor, the appearance of a mouldy corpse; he wore no visible linen; an old black frock-coat tightly covered his lean, withered limbs'—so Tocqueville described his impressions of the man.[5] George Sand described him as the 'Marat of our time', while to Marx he was 'the head and heart of the proletarian party in France'. Two hundred thousand Paris workers followed his coffin, among them Clemenceau and Louis Blanc. At his graveside, representatives of every Socialist and Anarchist trend in France spoke in his honour. Prominent among them was Édouard Vaillant, at one time a member of the General Council of the International, and later one of the founders of the United Socialist party of France.

The first uprising instigated and led by Blanqui was that of the Conspiracy of the Seasons. It was also the last to take place until the end of the July Monarchy. On 12 May 1839, several hundred of Blanqui's followers took over the arsenals in the suburbs of Saint-Denis and Saint-Martin and threw up barricades. But the uprising was overwhelmed on the same evening. Blanqui and other leaders were arrested.

The League of the Just had taken part in the conspiracy. Its sections had marched with the others and were involved in the general defeat. Two leaders of the League, Karl Schapper, a printer, and Heinrich Bauer, a shoemaker, were also arrested and eventually, together with Joseph Moll, expelled from France.[6] They went at once to London.

Soon after their arrival they formed a new organization. Since there was complete freedom of association and assembly in England, they decided on a public body—the German Workers' Educational Society—as a propaganda front for their secret organization. The society, which began in February 1840, lived on through many historic upheavals. It was dissolved only at the end of 1917, during the First World War, when the British government interned German citizens.[7]

The Workers' Educational Society and, with it, the League, soon assumed an international character. It was joined by Scandinavians, Dutchmen, Hungarians, Czechs and south Slavs, together with a handful of Russians and Alsatians. As it propagated the idea of Communism, it changed its name to the Communist Workers' Educational Society. Its membership card carried in twelve languages the slogan: 'All men are brothers'. In 1845, five years after it was founded, the society had more than 500 members. It met in a public house in Soho, a working-class district in the centre of London inhabited by colonies of exiles, where later Marx was to live for a number of years. According to the Northern Star, the walls of the big, lofty meeting-hall carried portraits of Shakespeare, Schiller, Mozart and Dürer, surrounded by flowers. There was a life-sized statue of a woman in a red Jacobin cap, bearing the symbols of liberty and equality. On either side of the speaker's rostrum stood a statue of freedom and justice, and above the chairman's seat was a painting representing the brotherhood of the working class. An enormous frieze along the four walls, surrounded by golden wreaths on a red background, bore in twelve languages the same sentence: 'All men are brothers'.[8] Although the main work of the Society was in London, its central direction remained for a time in Paris. It was transferred to London only in the autumn of 1846, when Schapper and Moll were entrusted with the leadership.

Besides a strong branch in London, in close contact with French refugees, the society also had groups in Paris, a number of sections organized by Wilhelm Weitling and Philipp Becker in the Swiss cantons of Geneva, Zurich, Berne, Waadt, Neuenberg and Aarau, and a number of small groups in Germany. But, if one can believe the reports of Metternich's police, its sphere of activity extended far beyond its own branches. 'In all workers' associations in Germany, France, England, Holland and Switzerland they are firmly entrenched and almost the dominant influence,' states one of these police reports from Zurich (15 June 1845), 'and all parts of the network keep in constant touch through correspondence, provide each other with mutual encouragement, inform each other of their plans and resolutions and warn each other if they are kept, more or less, under police observation.'[9]

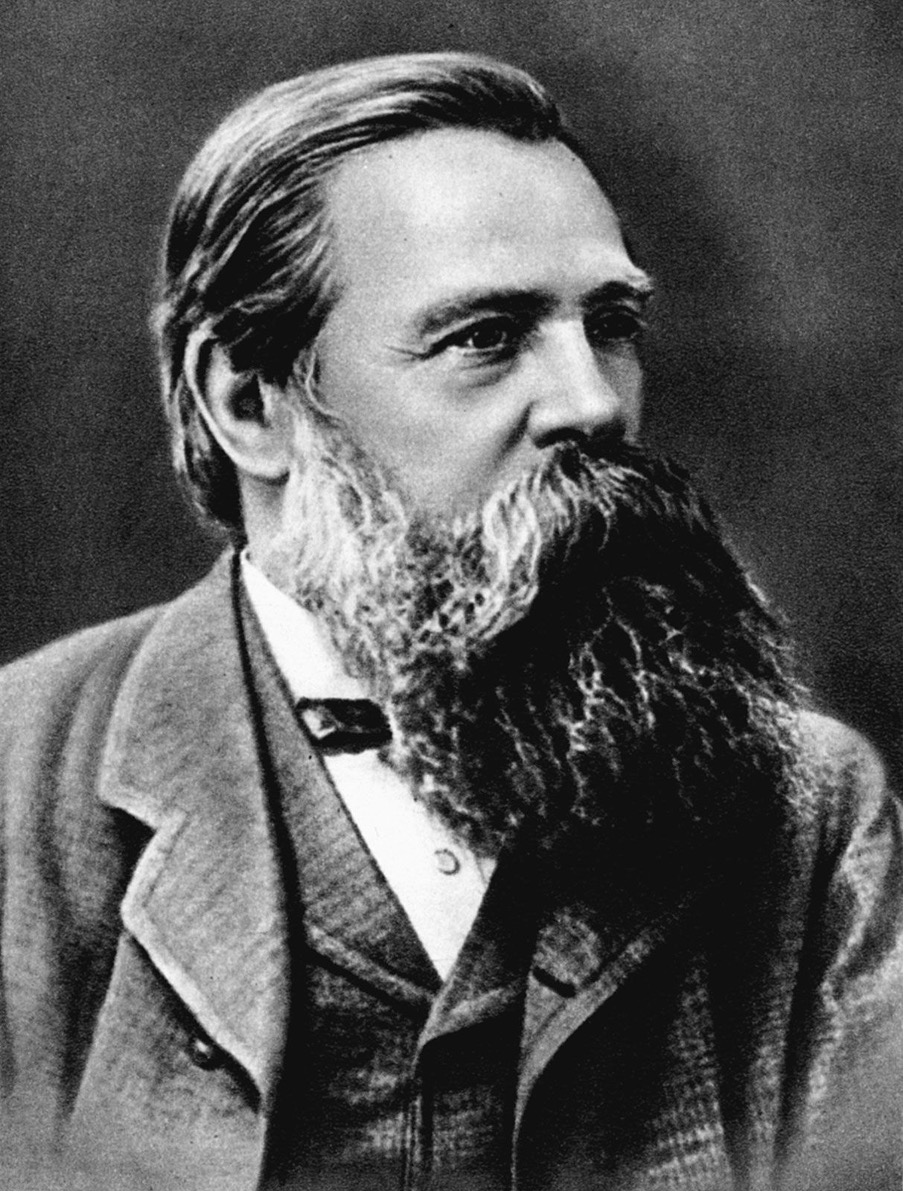

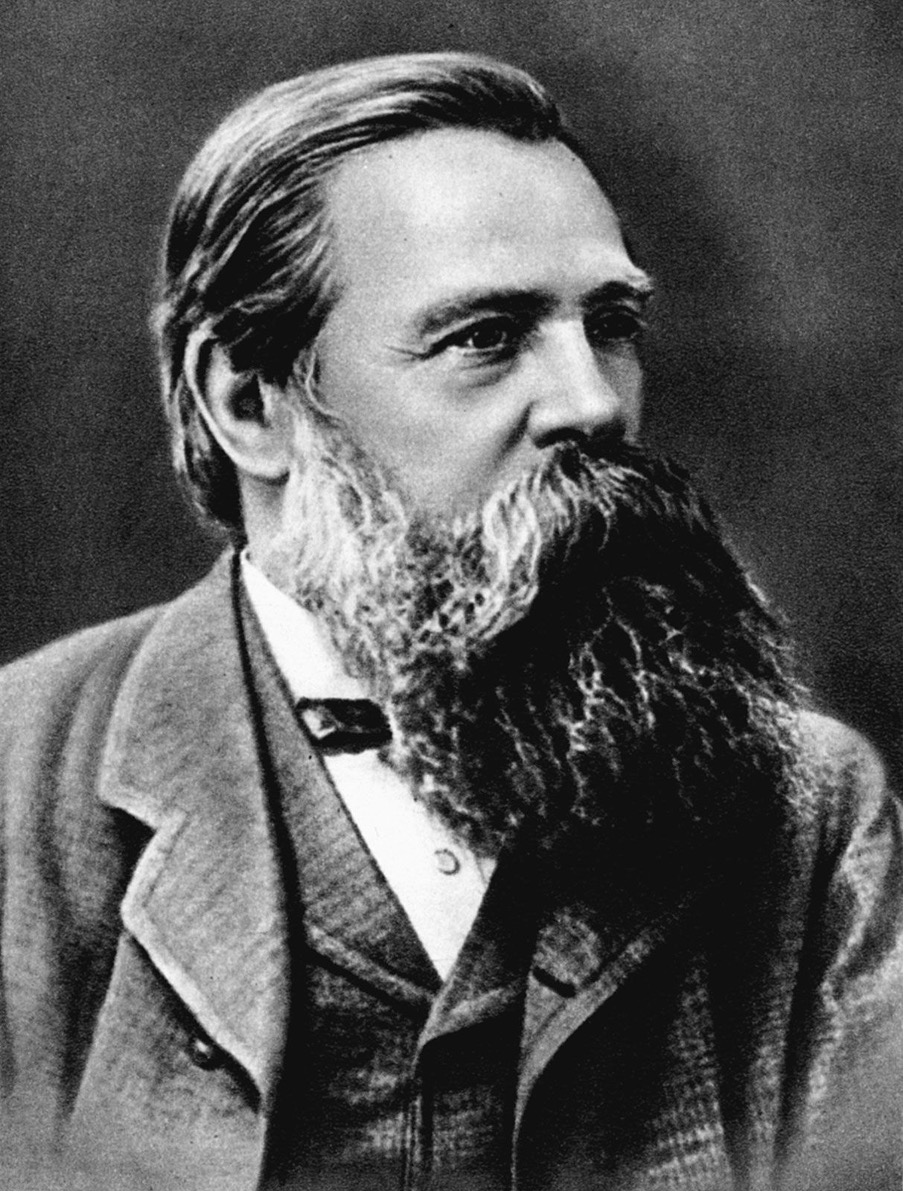

Friedrich Engels arrived in London in November 1842, visited the Workers' Educational Society and met its leading members, Schapper, Bauer and Moll. They left on him, as he recounted more than forty years later, a 'deep impression'. This was especially true of Schapper (1813–70), who had taken part, as a student of forestry, in Georg Büchner's agitation among the peasants of Hesse. A year later, with a group of fellow conspirators, he broke into the police guard-room in Frankfurt, and then fled the country. In 1834 he joined Mazzini's campaign in Savoy for the liberation of Italy from Austrian rule. In 1836 he founded the League of the Just. Together with Blanqui, he attempted the coup d'état of May 1839. Engels described him as 'of gigantic stature, resolute and energetic, always ready to jeopardize his means of livelihood and life itself. In the 1830s he fulfilled the role of professional revolutionary, of which he was a superb example.'[10]

When Marx, who was still living in Brussels in the summer of 1845, paid his first visit to England in the company of Engels, his friend introduced him to the Workers' Educational Society. Marx was most impressed by the spirit of the society and the theoretical interests of its leaders. Up to that time, he had held aloof from secret societies and refused to take them seriously. He was repelled by their atmosphere of romantic conspiracy and their confused utopian ideals. His own outlook was quite free of romanticism. He saw in the working class the force which would overturn capitalism. The Blanquist conception of social revolution proceeding from an armed coup d'état was completely alien to him. In English Chartism he saw a hopeful example of an independent, class-conscious workers' movement. What they still lacked, as did the budding Labour movement in other countries, was a clear recognition of their historic aims.

When Marx visited the league in London, the members were engrossed in a discussion with Weitling, lasting over many weeks, about the essence and prospects of Communism.

Wilhelm Weitling (1808–71) was born in Magdeburg, the illegitimate son of a French officer and a German seamstress. After a childhood of poverty and privation, he had learned the tailoring trade. His great abilities as writer and speaker, his idealism and his manifest integrity won him an enthusiastic following among the German workers. 'He is a fanatic,' remarks Wilhelm Marr, who had long watched his development with interest, adding that 'his enthusiasm for the cause has almost the character of a religious mania'.[11] He was, as Marx said, an 'athletic figure', one of the outstanding personalities of early German Socialism. His brooding mind, nourished by the Bible as well as by the French Socialist writings of Fourier, Cabet and Lamennais, fashioned for itself a curious vision of a Christian Communist Utopia.

As a wandering handicraftsman, Weitling arrived in Paris in 1837, and soon joined the League of the Just. He apparently expounded his version of Communism with great effectiveness, since he was commissioned by the central committee to 'put into writing his demonstration of the possibility of Communism'.[12] It appeared in 1838 under the title, Die Menscheit, wie sie ist und wie sies sein sollte. Four years later in Switzerland, to where he had moved in 1841, he published his main work entitled Garantien der Harmonie und Freiheit. Marx rated it the 'brilliant début of the German worker'. The book obtained a surprisingly large circulation, not only in Switzerland, but also in Germany and Austria, where despite a close police watch and under threat of heavy gaol sentences (in Austria there was even the danger of the death penalty), it was smuggled across the borders by travelling artisans. The first edition of 2,000 in 1842 was followed by a second, printed in Hamburg in 1844, and a third in 1849. The book was also translated into French, English and Norwegian.[13]

Weitling's career in Switzerland, as organizer, propagandist and writer, came to an abrupt end in 1843. He had written a new book, Das Evangelium eines armen Sünders, and had publicly invited subscriptions. In his advertisement he claimed to have proof 'in over a hundred places in the Bible' that Christ was a prophet of freedom and a forerunner of Communism. This, in the view of the sanctimonious ecclesiastical court at Zurich, was veritable blasphemy, and the public prosecutor was asked to institute criminal proceedings. The book was confiscated and its author arrested. He spent ten months in prison on remand and was then sentenced to six months in gaol and life-long banishment from Switzerland. After that, gagged and handcuffed, he was taken to the German border and handed over to the police in Baden. They passed him on to the Prussians. Weitling, after a good deal of moving from place to place, arrived in London in September 1844.

In London he was received with great honour. The Workers' Educational Society arranged an international banquet, at which English and French as well as German speakers paid tribute to him as a 'martyr in the cause of Communism'. This was the first international Socialist demonstration; as such, it was a factor in the formation of the Society of the Democratic Friends of All Nations, whose importance for the history of the International will be considered later.

Inevitably, Weitling was invited to attend the weekly discussions of the Workers' Educational Society, to explain in more detail his ideas on Communism. The minutes of these discussions, mainly between Weitling and Schapper, were published in 1922 by Max Nettlau. They provide us with a great deal of insight into the world of ideas of early German Socialism.[14] From them it is clear that Schapper and his friends did not accept Weitling's version of Socialism. Despite the veneration with which he was received in London, his intellectual leadership was rejected.

Marx's first visit to England coincided with the Weitling debate, and he must have been kept fully informed. He saw the value of the league, both as a means of theoretical development and as an instrument of Communist propaganda. But he also saw that this propaganda must have a clear basis in theory, and that the theory should derive, not from abstract ideas or chains of deductive reasoning, but from existing social and economic conditions.

The Socialist ideas from which the members of the Communist League derived their inspiration were many and varied. Saint-Simon, Cabet, Fourier, Proudhon, Blanqui, Louis Blanc, Robert Owen and Wilhelm Weitling were among the main contributors. Marx found value in many of their ideas, while rejecting the methods and body of such thinking as utopian. After returning to Brussels it seemed very necessary to him, as we find from the outlines and plans which he projected at the time, to develop some clarity on the main question of Socialist theory. This called for sustained discussion and the detailed elaboration of a programme. His first idea, after returning to Brussels, was to found an international journal which would serve as a forum for discussing all trends in the Socialist movement. When this plan misfired, he formed together with Engels in 1846 a 'Communist correspondence committee', which was intended to develop and inspire the various sections of the league through letters and circulars.

The league's central committee in London also came to the conclusion that the movement required a programme. In the autumn of 1846 they called for the following year a congress in London which would represent every section of the league and would have the task of preparing a common programme. At the same time, they decided to invite Marx and Engels to draft the programme.

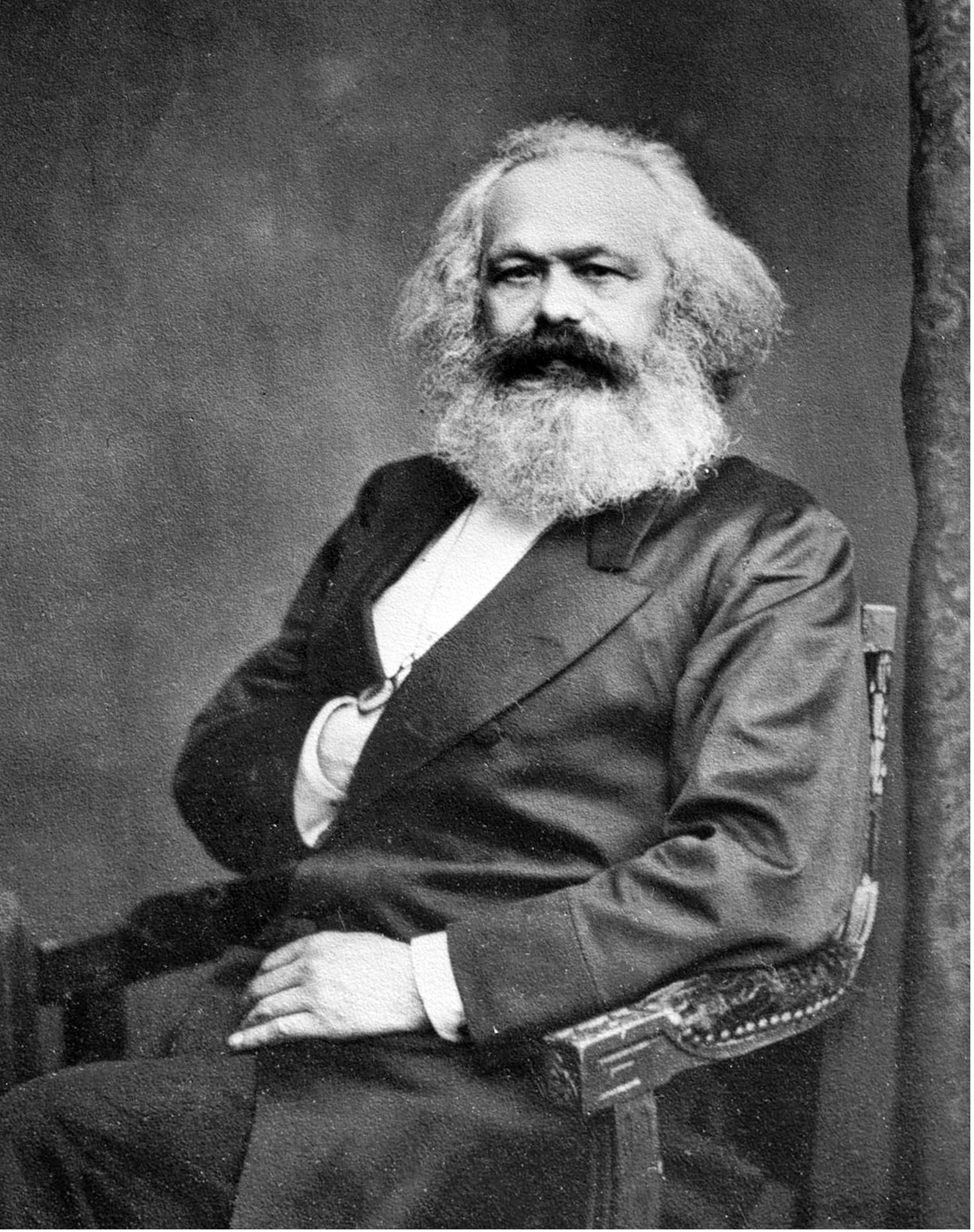

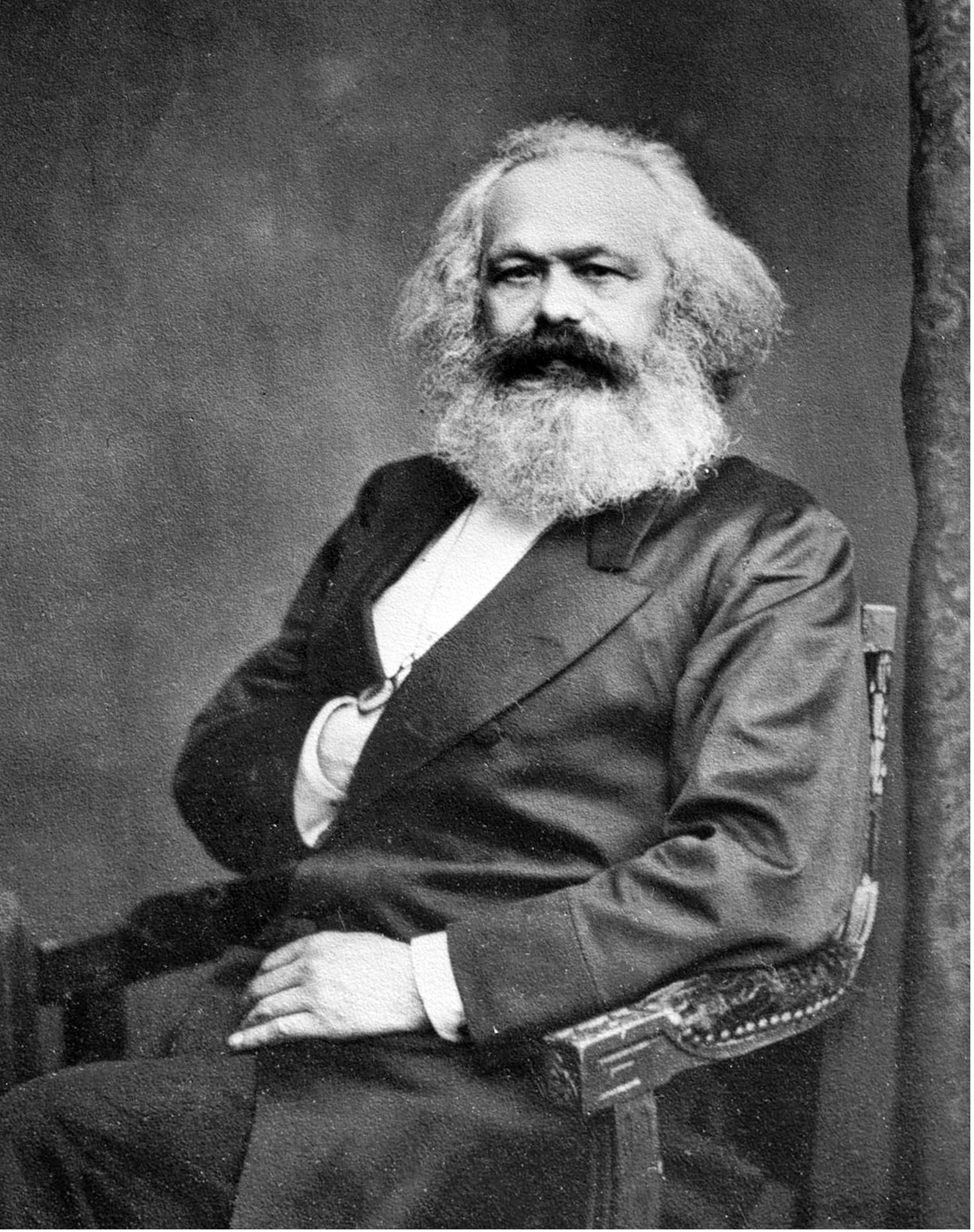

Marx, though still only twenty-eight, was already known as the leading representative of democracy and Socialism in Germany. His critical writings in the Rheinische Zeitung, which he had edited when barely twenty-four, had established his reputation as one of the foremost political and philosophical writers of the time. 'Think of Rousseau, Holbach, Lessing, Heine and Hegel combined in one person—I say combined and not thrown together—and you have Dr Marx,' declared Moses Hess in a letter (2 September 1841) to Berthold Auerbach.[15] The line of the paper was much too advanced for the Prussian government to tolerate, and it was soon suppressed. In Paris, to which he had moved later in 1843, Marx wrote his Kritik der Hegelschen Rechtsphilosophie in 1844, and in Brussels, where he first settled after being expelled from France in 1845, he wrote Die Heilige Familie, a criticism of the contemporary philosophical schools. All the leading ideas, which were later to comprise what became known as Marxism, were contained in embryo in that book. Meanwhile Engels, two years younger than Marx, had made a reputation for himself through a book appearing in 1845, entitled The Condition of the Working Class in England, and through his contributions to the Chartist Northern Star. The central committee of the league was most anxious to secure the collaboration of Marx and Engels in formulating the party programme. On behalf of the central committee, Joseph Moll visited Brussels at the beginning of 1847 to invite both of them to the congress. According to Engels, Moll said that the league 'was convinced of the general correctness of our conception as well as of the necessity to free the league from all conspiratorial traditions and forms of organization'. The Congress of the League would give Engels and Marx the opportunity of 'developing their critical Communism in a manifesto, which would then be published as the Manifesto of the League'. Marx and Engels accepted the invitation.

The Congress of the League met in London on 1 June 1847. Engels attended as the representative of the Prussian branch of the Communist Correspondence Committee, while Wilhelm Wolff represented its Brussels branch. Marx was unable to attend, owing to lack of money.

The congress decided to transform the league into a propaganda organization, to reorganize it along democratic lines, with an elected executive committee which would be subject to replacement, and to get rid of the 'old mystic name, a hangover from the period of conspiracy', as Engels termed it. It called itself from then on the Communist League. The first article of the draft statutes declared the aim of the league to be 'the downfall of the bourgeoisie, the rule of the proletariat, the overthrow of the old society of the middle class, based on class distinction, and the establishment of a new society without classes and without private property'. It was agreed to submit the draft statutes to the branches for discussion, and to meet again in the late autumn for a final decision. It was also agreed to consider, at the second congress, the draft of a programme for the league and to publish in the meantime a monthly journal. The first and only issue of the journal, known as the Kommunistische Zeitschrift and edited by Schapper, appeared in September. Above the title, the journal carried the slogan, 'Proletarians of all lands, unite!'

The second congress met in London with Schapper as chairman on 30 November 1847. There were delegates of branches from England, France, Belgium and Germany, and this time Marx himself was able to come. Between the first and second congresses, Marx had founded, together with Wilhelm Wolff, Joseph Weydemeyer, and Edgar von Westphalen, one of Marx's brothers-in-law, the Brussels section of the German Workers' Educational Society. According to Marx's report to the second congress, its membership was already 105.[16]

The first item at the congress was the final form of the statutes which were to define the new structure of the League. It was to consist of local circles, leading circles, a central governing body and a congress. The congress, as the highest authority, was to meet annually in August, and the central governing body, elected by congress and responsible to it, was to act as the executive. Since there was at the time hardly a country outside England where a workers' organization could openly propagate Communist views, workers' educational societies were to be established and directed by secret organization. But the main point on the agenda was the party programme, the leading ideas of which had been debated during the ten days of the congress. Marx and Engels were instructed to draft it. The decision was of historical importance, because it gave rise to a document which was to prove almost without rival in its power to affect the entire future course of social thinking.

The Communist Manifesto,[17] which supplied the Communist League with its programme, is notable for the bold, messianic sweep of its ideas. The triumph of Socialism is presented as the outcome of an iron historical necessity; the development of the productive forces and the class struggles which stem from it must inevitably give rise to 'a revolutionary change in the whole of society'. 'In place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class differences,' said the Manifesto, 'appears an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.'

Embodied in the Manifesto is another messianic theme: the idea that the working class cannot free itself from the exploitation and oppression under which it suffers without at the same time liberating the whole of society. Consequently, the emancipation of the working class would emancipate the whole human race from all traces of social injustice. This idea infused the struggle of the workers for their own interests with a moral as well as a historical significance. It supplied the class struggle with a double objective: the moral notion of freedom and equality for all human beings, together with the prediction that the transformation of capitalism into Socialism is inherent in the social process.[18]

While the Manifesto was being written, Europe was poised on the threshold of revolution. The feeling that a great social convulsion was pending runs through a good many passages in the document. When the congress met in London at the end of November, news came through that the Swiss government, defying the threats from Russia, Austria, Prussia and France, had overthrown the reactionary Catholic separatist party. In January 1848, with Marx still at work on the Manifesto, revolts broke out in Lombardy and Sicily, and revolutions in Naples, Turin and Florence. Marx predicted that the revolution would spread to France and Germany. The Manifesto pointed to the imminence of a social upheaval.

The Manifesto appeared in London in the German language in the beginning of February 1848. About a fortnight later, revolution broke out in France. A peaceful demonstration demanding electoral reform was fired on by soldiers in the streets of Paris on 23 February. Next day the lower orders had, in Tocqueville's words, 'suddenly become masters of Paris'. Having made a thorough study of the Revolution of 1789 and personally witnessed the revolutions of 1830 and 1848, Tocqueville was at once aware of the presence of a new social element in the latest outbreak. For the first time in history, he wrote, it was a revolution 'made entirely outside the bourgeoisie and against it.…This time it was not only the question of a party; the aim was to establish a social science, a philosophy, I might also say a religion…this was the really new portion of the old picture.'[19]

When news of the outbreak of revolution in France reached London, the league's central committee decided to transfer its powers to the Brussels district committee; this in turn authorized Marx to set up a new central committee in Paris. Schapper, Moll and Heinrich Bauer from London, Marx, Engels and Wolff from Brussels, moved to Paris at the beginning of March.

But before Marx could get the new central committee going, he was forced to take on his own responsibility a political decision which was to cause a good deal of discord among the German émigrés in Paris. There were then in the city thousands of refugees from Belgium, Italy, Poland and Germany. They naturally gave a rapturous welcome to the new French revolution. Inevitably too there was a revival of the earlier tradition of revolutionary legions of foreign refugees who had fought beside the French revolutionary armies in 1792 and 1793 for the liberation of their fatherland. The Society of German Democrats, which had just been established under the leadership of the poet Georg Herwegh, decided to form a German Revolutionary Legion.

The meeting which took this decision was held on 6 March, the day after Marx's arrival in Paris. Marx attended the meeting and spoke against the idea. He insisted that revolution could not be carried at the point of a bayonet from a foreign country into one's native land. An armed invasion from outside would serve only to strengthen local absolutism, since it would be able to appeal to the patriotic feelings of the masses and rouse them in defence of their national independence. Marx advised the workers to return singly to Germany and work for revolution on their home ground.

The new central committee of the league, which was set up soon afterwards with Marx as president and Schapper as secretary, agreed entirely with Marx. It drew up for the impending German revolution a list of 'Demands of the Communist Party of Germany'. The first of the seventeen points read: 'The whole of Germany will be declared a single, indivisible republic.' The central committee went on to form a German Communist club, which organized the return of hundreds of refugees to Germany. And when revolution broke out on 13 March in Vienna and on 18 March in Berlin—as Marx had foreseen, the 'crow of the Gallic cock' had given the signal—most of the league's members hurried back and were soon at the head of the working-class movement. Marx and Engels went to Cologne and founded the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, which became the leading organ of the revolution. Its first number appeared on 1 June 1848.

Marx and Engels now thought that the league had become superfluous. Marx told a meeting of its leading members in Cologne, soon after his arrival, that it was 'not a conspiratorial but a propagandist' organization. 'Under existing conditions, they could make propaganda openly, and there was no need for secrecy, as they enjoyed freedom of the press and of assembly.' He proposed the dissolution of the league, and when Schapper and Moll protested, Marx used the authority delegated to him in Paris to dissolve it himself.[20]

After the defeat of the European revolution, the league was revived in London in the late autumn of 1849. After his expulsion from Cologne in May and from Paris in August 1849, Marx had moved to London, as had the members of the old central committee. Only Moll was missing; he had fallen in the fighting at Baden.

The league anticipated an early resumption of revolution, 'called forth by an independent uprising of the French proletariat or through the intervention of the Holy Alliance against the revolutionary Babel', according to the First Address of the Central Committee to the League, edited by Marx in March 1850. The Address gave clear directions for the conduct of the working class in the next revolution, and ended with the battle-cry, 'the revolution in permanence'. In June 1850 Marx still believed, as he stated in his second Address, 'that the early outbreak of a new revolution could not be far away'.[21]

Soon both Engels and Marx began to have their doubts. In a joint investigation into the revival of world trade, they had acknowledged it to be the main reason for the triumph of counter-revolution. The economic crisis of 1847—the 'mother of the revolution'—had been surmounted in 1849. A period of prosperity had begun. This prosperity was, they declared, 'the mother of counter-revolution'. These studies led them to the conclusion that the period of revolutions was temporarily at an end. 'With this general prosperity,' wrote Marx, 'there can be no question of a real revolution.…A new revolution is only possible as the result of a new crisis.'[22]

The question of the possibility of an early revolution gave rise to a conflict in the league which culminated in a split at the meeting of the central committee on 15 September 1850.[23] A group led by Schapper and Willich expected a new evolution in the very near future, and demanded that the league should frame its policy accordingly.[24] In the spirit of the Blanquist doctrine of the revolution in permanence—this was the slogan with which the Address of Marx 1850 concluded—they saw in the revolution merely a problem of military strategy and will-power on the part of the resolute leadership. They believed that the working class could win power in the next revolution and could secure its permanent supremacy, providing that the right 'measures' were taken.

This was the lesson they had deduced from the history of the revolutions in 1789, 1830 and 1848. The course of events between 1789 and 1793 had proved that the working people could win if they were united, took up arms, and fought courageously on the streets for political power. July 1830 and February 1848 in Paris, March 1848 in Vienna and Berlin had seemed to confirm the lesson even more strongly. What had happened yesterday could happen again tomorrow. If the proletarian revolution had so far failed, they explained, this was due solely to the 'mistakes' of the leadership.

Schapper and Willich had lived through the battles, the triumphs and the failures of 1848. August Willich, a former Prussian officer, now a fervent revolutionary Socialist, had fought together with Engels in a guerrilla detachment during the Baden-Pfalz campaign. Foremost in his mind was the need for a military dictatorship to be established on the day of revolution. Schapper had explained to Weitling the need for the workers to be 'ready' for revolution. From the events of 1848, however, he had concluded that the intellectual and moral maturity of the leadership was above all the decisive factor.

Schapper and Willich were not the only ones to expect an early recurrence of the revolution. The colonies of French, Italian, Polish, Hungarian and German refugees in London resounded with vehement discussions on the same theme. They drafted revolutionary programmes and debated the composition of revolutionary governments. The poet Gottfried Kinkel, a modest man who nevertheless carried the romantic halo of revolutionary heroism, had the idea of raising a loan in America and England for financing a revolution in Germany. This was enthusiastically supported by the German refugees, and particularly by Schapper, Willich and Weitling.

Marx disdainfully rejected what he considered to be 'playing with revolution'. He did not believe that a revolution could be unleashed simply by the power of a dedicated leadership. It sprang, in his view, from a complex of particular political, economic and social conditions. Nor did he believe that society could leap over the phase of bourgeois revolution. 'There can be, for the time being, no talk of achieving Communism; the bourgeoisie must first take the rudder,' he declared, in the course of a vehement discussion with Weitling.[25] Marx repeated the same idea in the Manifesto. But as early as 1846 he had rejected Weitling's 'playing with revolution' with the remark: 'To arouse fantastic hopes can never relieve the conditions of the suffering; it can lead only to their ruin.'[26]

Marx had been confirmed in these ideas through the experience of revolution and counter-revolution in 1848. 'Louis Blanc had provided the best example,' he told Schapper, 'of the result of coming to power too soon.' His attempt to achieve the 'right to work' through the experiment with 'national workshops' had culminated in the massacre of the Paris workers on 24 June 1848. Marx went on to explain that 'whilst we say to the workers: you have to undergo fifteen, twenty, fifty years of civil war and national wars in order to change the conditions, and to qualify yourselves for governing, they were told instead: we must either come to power at once or retire to our beds'.

The discussion ended with the decision that the two sections of the Communist League should part company. This was the last meeting of the central committee. It was formally transferred to Cologne. Schapper and Willich, supported by a majority of the London members, formed a separate organization.

The Communist League had never been a mass organization. Its members, grouped together in small local sections, had committed by their rules to 'revolutionary zeal and vigorous propaganda', had acted as seed-carriers of Socialism in workers' educational, athletic and choral societies. In Schleswig-Holstein and Mecklenburg they had also been active in unions of peasants and wage-earners.

The German governments became alarmed at the extent of Communist propaganda, which they assumed to be centred in London, under the leadership of Marx. In the spring of 1851 the Prussian government considered proposing, jointly with Austria and Russia, that the British government should 'render the chief revolutionaries, whose names are known, ineffective as declared enemies of the European political and social order…by deporting them to the colonies'.[27] King Frederick William IV favoured a more realistic, if in his own words less 'above-board', approach. In a letter which he personally wrote to his prime minister, Freiherr von Manteuffel, he ordered 'the public exposure of this network of subversive conspiracy, so that the people of Prussia may derive full value from the spectacle of a plot discovered and, in particular, its perpetrators amply punished'. The king recommended the Prussian chief of police, Wilhelm Stieber, as the man for this somewhat unsavoury task.[28]

Stieber was duly given the assignment. An unexpected stroke of luck put him on the trail of eleven members of the League. They were arrested in May 1851 and brought to trial on 4 October 1852 after a year and a half in prison. As the coach surrounded by dragoons arrived with the prisoners in front of the court-house, they were greeted, according to an eye-witness, with 'a loud, resounding "Hoch" from a large crowd of people with bared heads'.[29] The prosecution charged the prisoners with 'having plotted to overthrow the constitution, to arm the citizens and inhabitants for a civil war against the throne and against each other'. In the indictment the state attorney added, as an aggravating factor, the charge that the party of the accused 'went so far…as to aim at the suppression of all feelings for God and man'.[30]

As the king had anticipated, the trial lasting five weeks was 'a prolonged spectacle', which revealed, in fact, extraordinarily little. In searching the houses of the accused, the police had found a number of publications, including the Manifesto and the Statutes of the Communist League, together with several circulars from the central committee. But none of these documents contained evidence of a 'plot' to foment civil war. Nor could they have done. The League was indeed a secret organization, since after the revolution had been suppressed in Germany no public propaganda for the ideas of Communism was possible. The League was a secret, but in no way conspiratorial, organization. Since the state attorney had no genuine documents with which to establish a plot to overthrow the government, Stieber undertook, most probably on the wishes of the king, to provide the incriminating documents himself. The grotesque story of the forgeries was described by Marx in his Enthüllungen über den Kommunistenprozess ze Köln.

On the jury benches sat six aristocrats, four members of the financial aristocracy and two state officials. The forgeries were exposed in the course of the trial. But the jury could not oppose the desire of the king to use the trial as a public demonstration of the retribution in store for plotters, even though no plot had been discovered. Six of the accused were given prison sentences of three to six years, with the loss of civil rights and subsequent police supervision. The others were acquitted. 'A degrading and completely unjust sentence,' wrote Varnhagen von Ense, who could hardly be suspected of treasonable sentiments, in his diary.

The government prepared everything with detestable thoroughness, kept the accused in custody for eighteen months, nominated its own jury and instigated every kind of knavery.…Everyone here with any legal knowledge was convinced that the accused could not have been sentenced under existing laws. But what have Prussian judges and Prussian jurymen allowed themselves to become? It causes me a good deal of distress.[31]

Although the trial had a considerable propaganda effect, it still meant the end of the Communist League. On Marx's suggestion, it dissolved itself soon after the sentences were announced. A few months later, the break-away league also faded out. Its former members had scattered. Heinrich Bauer had emigrated to Australia, Weitling, Ewerbeck and Willich to America. Willich became a brigadier-general in the American Civil War, and was severely wounded at the battle of Murfreesboro' in Tennessee. Engels had gone back to his father's textile factory in Manchester. Marx had started work on Das Kapital. When, after another twelve years, the International Working Men's Association began life, its general council included from the former members of the Communist League Marx, Engels, Georg Eccarius, Karl Pfänder and Friedrich Lessner.

1. Alexis de Tocqueville, Recollections (London, 1948), pp. 2–3.

2. cf. Paul Louis, 'Blanqui und der Blanquismus', Die Neue Zeit (1900–1), vol. II, p. 76.

3. For the story of Blanqui's life, see Neil Stewart, Blanqui (London, 1939); Gustave Geffroy, L'Enfermé—Auguste Blanqui (Paris, 1897); for a brief account of his ideas, see Paul Louis, op. cit., vol. II; for a comprehensive examination, see Alan B. Spitzer, The Revolutionary Theories of Louis-Auguste Blanqui (New York, 1957).

4. Marx defined the characteristics of Blanqui's version of Socialism as follows: 'This Socialism means a commitment to permanent revolution, to revolutionary class dictatorship, to the class dictatorship of the proletariat as a milestone on the way to the abolition of all class distinctions and the mode of production on which these distinctions are based, and of the ideas which follow from these social relationships'—Karl Marx, Die Klassenkämpfe in Frankreich (Berlin, 1951), p. 130.

5. Tocqueville, op. cit., p. 138.

6. Weitling, who was an eye-witness of the barricade fighting, mentions another German worker who participated: 'The last barricade was stormed. Barbès himself sank wounded to the ground.…One man remained standing by his side though wounded, a German shoemaker, Austen, from Danzig'—Garantien der Gerechtigkeit und Freiheit (Hamburg, 1849), p. 14.

7. See B. Nikolaevsky, 'Towards a History of the Communist League, 1847–59', International Review of Social History, vol. I (1956), p. 236.

8. John Saville, Ernest Jones, Chartist (London, 1952), p. 92. For the history of the Communist Workers' Educational Society, see W. Brettschneider, Entwicklung und Bedeutung des deutschen Frühsozialismus (Königsberg, 1936), and Friedrich Lessner, 'Vor und nach 1848, Errinerungen eines alten Kommunisten', Deutsche Worte (1898).

9. Quoted in Ludwig Brügel, Geschichte der österreichischen Sozialdemokratie (Vienna, 1922), vol. I, p. 43.

10. Friedrich Engels, introduction to the third edition of Karl Marx's Enthüllungen über den Kommunistenprozess zu Köln (1885); Engels's summary of the history of the Communist League was supplemented by a number of important documents in Franz Mehring's introduction to the fourth edition of the book (1914).

11. W. Marr, Das junge Deutschland in der Schweiz (Leipzig, 1846), p. 45. See also Otter Brugger, Die Wirksamkeit Weitlings 1841–3 (Berne, 1932), and Robert Grimm, Geschichte der sozialistischen Ideen in der Schweiz (Zurich, 1931).

12. Max Nettlau, 'Londoner deutsche Kommunistische Diskussionen, 1845', in Archiv für die Geschichte des Sozialismus und der Arbeiterbewegung, vol. X, p. 363.

13. Emil Kaler, Wilhelm Weitling (Hottingen, Zurich, 1887), p. 38; see also Otto Brugger, Geschichte der deutschen Handwerkervereine in ber Schweiz (Berne, 1932), and Carl Wittke, The Utopian Communist, Wilhelm Weitling (Louisiana, 1950).

14. Nettlau, op. cit., pp. 362–91.

15. Moses Hess Briefwechsel, edited by Edmund Silberner (The Hague, 1959), p. 80.

16. Max Nettlau, 'Marxanalekten', Archiv für die Geschichte des Sozialismus und der Arbeiterbewegung, vol. III, p. 397.

17. In his Introduction to the German edition of the Communist Manifesto of 1890, Engels explained why at the time of its drafting in 1847 it could not be called Socialist. 'Socialist' was at that time applied to the representatives of Utopian ideas who stood outside the working class and directed their appeal to the 'educated' classes. 'Communists' was the term applied to those who stood for a 'thorough reconstruction of society', and who appealed to the working class. 'Socialism,' explained Engels, 'referred to a bourgeois movement; Communism, to a working-class movement.'

18. For a historical appreciation of the Communist Manifesto, republished at its centenary by the British Labour party in acknowledging 'its indebtedness to Marx and Engels as two of the men who have been the inspiration of the whole working-class movement', see Harold J. Laski, Communist Manifesto, Socialist Landmark (London, 1948); for a comprehensive analysis of the Manifesto, see Cole, op. cit., vol. I, pp. 247–62.

19. Tocqueville, op. cit., pp. 78–9.

20. On the dissolution of the Communist League in 1848, see the very informative statement of Peter Gerhardt Röser, chief among the accused at the Communist trial. It has bee taken from the files in the Berlin police headquarters and published as an appendix in Otto Mänchen-Helfen and Boris Nikolaevsky, Karl und Jenny Marx (Berlin, 1933), p. 152.

21. The full text of both Addresses is published as an appendix to Marx, Enthüllungen über den Kommunistenprozess ze Köln.

22. Neue Rheinische Zeitung. Politisch-ökonomische Revue, nos. 5 and 6 (1850).

23. For the Minutes of the last meeting of the central committee, see Nikolaevsky, op. cit., pp. 248–52.

24. In a circular to the members of the Communist League, Schapper and Willich gave their own version of the reasons for the split as follows: 'The only difference of principle between us and them [Marx and his cormades], while we were still united, was that they told the people that we should have to be in opposition for at least fifty years, which would mean acting purely as critics. We thought and still think that, given the right organization, our party will be able to put through such measures in the next revolution as to lay the foundation for a workers' society.' The circular, under the title, Ansprache der Partei Willich für das erste Quartal 1851, can be found in Appendix XVI to the collection of documents, Die Kommunistischen Verschwörungen des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts, vol. I (Berlin, 1853), p. 276, published by the Royal Prussian Directorate of Police, Dr Wermuth and Dr Stieber.

25. See Weitling's letter to Moses Hess of 31 March 1846 concerning his argument with Marx in Moses Hess Briefwechsel, p. 151. The argument took place at a meeting of the Communist Correspondence Committee on 30 March 1846 in Brussels. Those present were Marx, Engels, the Belgian Philippe Gigot and the Germans Louis Heilberg, Sebastian Seiler, Edgar von Westphalen, Wilhelm Weitling and Joseph Weydemeyer. The Russian liberal writer, P. W. Annenkov, attended as a guest.

26. See Annenkov's account of the meeting in Mänchen in Nikolaevsky, op. cit., p. 104.

27. Aus den Akten des Deutschen Zentralarchivs II, in Karl Obermann, Zur Geschichte des Bundes der Kommunisten 1849 bis 1852 (Berlin, 1955), pp. 6–7. See also the letter from the Austrian Ambassador in London, B. Koller, to his prime minister, Prince Schwarzenberg, on 8 June 1850, about his conversation with the British Home Secretary, Sir George Grey. He had informed the minister that the members of the Communist League, whose leaders were Marx, Engels, Bauer and Willich, 'even discussed regicide', and he suggested that they be prosecuted. According to Koller, Grey replied that 'under our laws, mere discussion of regicide, so long as it does not concern the Queen of England and so long as there is no definite plan, does not constitute sufficient grounds for the arrest of the conspirators'. From the 'Osterreichischen Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv', quoted in Ludwig Brügel, Aus den Londoner Flüchtlingstagen von Karl Marx, in Der Kampf, XVII (1924), p. 237.

28. For the letter, in the king's handwriting, see Mehring, op. cit., p. 165. Frederick Wilhelm really believed that the League was plotting against his own life, as he wrote, in 1849, to Bettina von Arnim. See Bettina von Arnim und Friedrich Wilhelm VI. Ungedrückte Briefe und Aktenstücke, edited by Ludwig Geiger (Frankfurt am Main, 1902).

29. See the letter from Bermbach to Marx in Mehring, op. cit., p. 165. A. Bermbach was a Cologne notary, a democrat, elected a deputy in the first Prussian House of Representatives in 1849.

30. Der Kommunistenprozess ze Köln 1852 im Spiegel der zeitgenössischen Presse, edited by Karl Bittel (Berlin, 1955), pp. 48–50.

31. Karl August Varnhagen von Ense, Tagebücher, vol. IX, p. 411, quoted in Obermann, op. cit., p. 125.