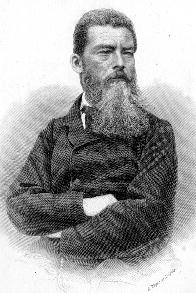

Ludwig Feuerbach 1839

Written: 1839 for Arnold Ruge’s Jahrbüche;

Source: The Fiery Brook;

Translated: by Zawar Hanfi, 1972;

Transcribed: by Eric Goodfield.

German speculative philosophy stands in direct contrast to the ancient Solomonic wisdom: Whereas the latter believes that there is nothing new under the sun, the former sees nothing that is not new under the sun; whereas oriental man loses sight of differences in his preoccupation with unity, occidental man forgets unity in his preoccupation with differences; whereas oriental man carries his indifference to the eternally identical to the point of an imbecilic apathy, occidental man heightens his sensibility for the manifold to the feverish heat of the imaginatio luxurians. By German speculative philosophy, I mean that philosophy which dominates the present – the philosophy of Hegel. As far as Schelling’s philosophy is concerned, it was really an exotic growth – the ancient oriental idea of identity on Germanic soil. If the characteristic inner movement of Schelling’s school is towards the Orient, then the distinguishing feature of the Hegelian philosophy and school is their move towards the Occident combined with their belittlement of the Orient. The characteristic element of Hegel’s philosophy as compared to the orientalism of the philosophy of identity is difference. In spite of everything, Hegel’s philosophy of nature does not reach beyond the involutions of zoophytes and molluscs to which, as is known, acephales and gastropodes also belong. Hegel elevated us to a higher stage, i.e., to the class of articulata whose highest order is constituted by insects. Hegel’s spirit is logical, determinate, and – I would like to say – entomological; in other words, Hegel’s is a spirit that finds its appropriate dwelling in a body with numerous protruding members and with deep fissures and sections. This spirit manifests itself particularly in its view and treatment of history. Hegel determines and presents only the most striking differences of various religions, philosophies, times, and peoples, and in a progressive series of stages, but he ignores all that is common and identical in all of them. The form of both Hegel’s conception and method is that of exclusive time alone, not that of tolerant space; his system knows only subordination and succession; coordination and coexistence are unknown to it. To be sure, the last stage of development is always the totality that includes in itself the other stages, but since it itself is a definite temporal existence and hence bears the character of particularity, it cannot incorporate into itself other existences without sucking out the very marrow of their independent lives and without robbing them of the meaning which they can have only in complete freedom. The Hegelian method boasts of taking the same course as nature. It is true that it imitates nature, but the copy lacks the life of the original. Granted, nature has made man the master of animals, but it has given him not only hands to tame animals but also eyes and ears to admire them. The independence of the animal, which the cruel hand robs, is given back to it by sympathetic ears and eyes. The love of art breaks the chains that the self-interest of manual work puts around the animal. The horse that is weighed down under the groom’s behind is elevated to an object of art by the painter, and the sable that is slain by the furrier for the purpose of turning its fur into a momentary ornament of human vanity is preserved by natural science so that it can be studied as a whole organism. Nature always combines the monarchical tendency of time with the liberalism of space. Naturally, the flower cancels the leaf, but would the plant be perfect if the flower only sat brightly on a leafless stem? True, some plants do shed their leaves in order to put all their energy into bringing forth the blossom, but there are other plants in which the leaf either appears later than the flower or simultaneously with it, which proves that any presentation of the totality of the plant requires the leaf as well as the flower. It is true that man is the truth of the animal, but would the life of nature, would the life of man itself be perfect if animals did not exist independently? Is man’s relationship with animals only a despotic one? Do not the forsaken and the rejected find a substitute for the ingratitude, scheming, and unfaithfulness of their fellow human beings in the faithfulness of the animal? Does the animal not have a power that consoles and heals his broken heart? Is not a good, rational sense also part of animal cults? Could it not be that we regard these cults as ludicrous because we have succumbed to an idolatry of a different kind? Does not the animal speak to the heart of the child in fables? Did not a mere donkey once open the eyes of an obdurate prophet?

The stages in the development of nature have, therefore, by no means only a historical meaning. They are, indeed, moments, but moments of a simultaneous totality of nature and not of a particular and individual totality which itself would only be a moment of the universe, that is, of the totality of nature. However, this is not the case with the philosophy of Hegel in which only time, not space, belongs to the form of intuition. Here, totality or the absoluteness of a particular historical phenomenon or existence is vindicated as predicate, thus reducing the stages of development as independent entities only to a historical meaning; although living, they continue to exist as nothing more than shadows or moments, nothing more than homoeopathic drops on the level of the absolute. In this way, for example, Christianity – and, to be sure, taken in its historical-dogmatic development – is determined as absolute religion. In the interest of such a determination, however, only the difference of Christianity from other religions is accentuated, thus neglecting all that is common to all of them; that is, the nature of religion which, as the only absolute condition, lies at the base of all the different religions. The same is true of philosophy. The Hegelian philosophy, I mean the philosophy of Hegel, that is to say, a philosophy that is after all a particular and definite philosophy having an empirical existence – we are not concerned here with the character of its content – is defined and proclaimed as absolute philosophy; i.e., as nothing less than philosophy itself, if not by the master himself, then certainly by his disciples – at least by his orthodox disciples – and certainly quite consistently and in keeping with the teaching of the master. Thus, recently, a Hegelian – and a sagacious and thoughtful person at that – has sought to demonstrate – ceremoniously and, in his own way, thoroughly – that the Hegelian philosophy “is the absolute reality of the idea of philosophy.”

But however sagacious the author is otherwise, he proceeds from the very outset uncritically in so far as he does not pose the question: Is it at all possible that a species realizes itself in one individual, art as such in one artist, and philosophy as such in one philosopher? And yet this is the main question; for what use to me are all the proofs that this particular person is the messiah when I do not believe at all that any messiah ever will, could, or must appear. Hence, if this question is not raised, it is quietly taken for granted that there must and does exist an aesthetic or speculative Dalai Lama, an aesthetic or speculative transubstantiation, and an aesthetic or speculative Day of Judgment. It is just this presupposition, however, that contradicts reason. “Only all men taken together, “says Goethe, “cognize nature, and only all men taken together live human nature.” How profound – and what is more – how true! Only love, admiration, veneration, in short, only passion makes the individual into the species. For example, in moments when, enraptured by the beautiful and lovable nature of a person, we exclaim: He is beauty, love, and goodness incarnate. Reason, however, knows nothing – keeping in mind the Solomonic wisdom that there is nothing new under the sun – of a real and absolute incarnation of the species in a particular individuality. It is true that the spirit or the consciousness is “species existing as species,” but, no matter how universal, the individual and his head – the organ of the spirit – are always designated by a definite kind of nose, whether pointed or snub, fine or gross, long or short, straight or bent. Whatever enters into time and space must also subordinate itself to the laws of time and space. The god of limitation stands guard at the entrance to the world. Self-limitation is the condition of entry. Whatever becomes real, becomes so only as something determined. The incarnation of the species with all its plenitude into one individuality would be an absolute miracle, a violent suspension of all the laws and principles of reality; it would, indeed, be the end of the world.

Obviously, therefore, the belief of the Apostles and early Christians in the approaching end of the world was intimately linked with their belief in incarnation. Time and space are actually already abolished with the manifestation of the divinity in a particular time and form, and hence there is nothing more to expect but the actual end of the world. It is no longer possible to conceive the possibility of history; it no longer has a meaning and goal. Incarnation and history are absolutely incompatible; when deity itself enters into history, history ceases to exist. But if history nevertheless continues in the same way as before, then the theory of incarnation is in reality nullified by history itself. The manifestation of the deity, which is only a report, a narration for other later times – and hence only an object of imagination and recollection – has lost the mark of divinity, and relinquishing its miraculous and extraordinary status, it has placed itself on an equal footing with the other, ordinary phenomena of history in as much as it is itself reproduced in later times in a natural way. The moment it becomes the object of narration, it ceases to be a miracle. It is therefore not without reason that people say that time betrays all secrets. Consequently, if a historical phenomenon were actually the manifestation or incarnation of the deity, then it must extinguish – and this alone would be its proof – all the lights of history, particularly church lights, as the sun puts out the stars and the day nocturnal lights; then it must illuminate the whole earth with its rapturous divine effulgence and be for all men in all times an absolute, omnipresent, and immediate manifestation. For what is supernatural must also act as such beyond all limits of time; and hence, what reproduces itself in a natural way – maintains itself only through the medium of either oral or written tradition – is only of mediated origin and integrated into a natural context.

The situation is the same with the theories of incarnation in the field of art and science. If Hegelian philosophy were the absolute reality of the idea of philosophy, then the immobility of reason in the Hegelian philosophy must necessarily result in the immobility of time; for if time still sadly moved along as if nothing had happened, then the Hegelian philosophy would unavoidably forfeit its at-tribute of absoluteness. Let us put ourselves for a few moments in future centuries! Will not the Hegelian philosophy then be chronologically a foreign and transmitted philosophy to us? Will it be possible for us then to regard a philosophy from other times, a philosophy of the past as our contemporary philosophy? How else do philosophies pass if it is not because men and epochs pass and posterity wants to live not by the heritage of its ancestors but by the riches acquired by itself? Will we therefore not regard the Hegelian philosophy as an oppressive burden just as medieval Aristotle once was to the Age of Reformation? Will not an opposition of necessity arise between the old and the new philosophy, between the unfree – because traditional – and free – because self-acquired – philosophy? Will not Hegelian philosophy be relegated from its pinnacle of the absolute reality of the Idea to the modest position of a particular and definite reality? But is it not rational, is it not the duty and task of the thinking man to anticipate through reason the necessary and unavoidable consequences of time, to know in advance from the nature of things what will one day automatically result from the nature of time? Anticipating the future with the help of reason, let us therefore undertake to demonstrate that the Hegelian philosophy is really a definite and special kind of philosophy. The proof is not difficult to find, however much this philosophy is distinguished from all previous philosophies by its rigorous scientific character, universality, and incontestable richness of thought. Hegelian philosophy was born at a time when mankind stood, as at any other time, on a definite level of thought, when a definite kind of philosophy was in existence. It drew on this philosophy, linked itself with it, and hence it must itself have a definite; i.e., finite character. Every philosophy originates, therefore, as a manifestation of its time; its origin presupposes its historical time. Of course, it appears to itself as not resting on any presuppositions; and, in relation to earlier systems, that is certainly true. A later age, nevertheless, is bound to realize that this philosophy was after all based on certain presuppositions; i.e., certain accidental presuppositions which have to be distinguished from those that are necessary and rational and cannot be negated without involving absolute nonsense. But is it really true that the Hegelian philosophy does not begin with any presuppositions? “Yes! It proceeds from pure Being; it does not start from a particular point of departure, but from that which is purely indeterminate; it starts from that which is itself the beginning.” Is that really so? And is it not after all a presupposition that philosophy has to begin at all? “Well, it is quite obvious that everything must have a beginning, philosophy not excepted.” Quite true! But “beginning” here has the sense of accidental or indifferent; in philosophy, on the other hand, beginning has a particular meaning, the meaning of the first principle in itself as required by philosophical science. But what I would like to ask is: Why should beginning be taken in this sense? Is the notion of beginning not itself subject to criticism? Is it immediately true and universally valid? Why should it not be possible for me to abandon at the start the notion of beginning and, instead, turn directly to that which is real? Hegel starts from Being; i.e., the notion of Being or abstract Being. Why should I not be able to start from Being itself; i.e., real Being? Or, again, why should I not be able to start from reason, since Being, in so far as it is thought of and in so far as it is an object of logic, immediately refers me back to reason? Do I still start from a presupposition when I start from reason? No! I cannot doubt reason and abstract from it without declaring at the same time that both doubting and abstracting do not partake of reason. But even conceding that I do base myself on a presupposition that my philosophizing starts directly from real Being or reason without at all being concerned with the whole question of a beginning, what is so harmful about that? Can I not prove later that the presupposition I had based myself on was only formally and apparently so, that in reality it was none at all? I certainly do not begin to think just at the point when I put my thoughts on paper. I already know how the subject matter of my thinking would develop. I presuppose something because I know that what I presuppose would justify itself through itself.

Can it therefore be said that the starting point taken by the Hegelian philosophy in the Logic is a general and an absolutely necessary starting point? Is it not rather a starting point that is itself determined, that is to say, determined by the standpoint of philosophy before Hegel? Is it not itself tied up with (Fichte’s) Theory of Science? Is it not connected with the old question as to the first principle of philosophy and with that philosophical viewpoint which was essentially interested in a formal system rather than in reality? Is it not linked with the first question of all philosophy: What is the first principle? Is this connection not proved by the fact that the method of Hegel – disregarding, of course, the difference of content which also becomes the difference of form – is essentially, or at least generally, the method of Fichte? Is this not also the course described by the Theory of Science that that which is at first for us is in the end also for itself, that therefore the end returns to the beginning, and that the course taken by philosophical science is a circle? Is it not so that the circular movement, and indeed taken literally, becomes an inner need or a necessary consequence where method; i.e., the presentation of philosophy, is taken to be the essence of philosophy itself, where anything that is not a system (taken here in its narrow sense) is not philosophy at all? For only that which is a completed circle is a system, which does not just go on ad infinitum, but whose end rather returns to its beginning. The Hegelian philosophy is actually the most perfect system that has ever appeared. Hegel actually achieved what Fichte aspired to but did not achieve, because he concluded with an “ought” and not with an end that is also beginning. And yet, systematic thought is by no means the same as thought as such, or essential thought; it is only self-presenting thought. To the extent that I present my thoughts, I place them in time; an insight that contains all its successive moments within a simultaneity in my mind now becomes a sequence. I posit that which is to be presented as not existing and let it be born under my very eyes; I abstract from what it is prior to its presentation. Whatever I therefore posit as a beginning is, in the first instance, that which is purely indeterminate; indeed, I know nothing about it, for self-presenting knowledge has yet to become knowledge. Hence, strictly speaking, I can start only from the notion of a starting point; for whatever object I may posit, initially it will always have the nature of a starting point. In this regard, Hegel is much more consistent and exact than Fichte with his clamorous “I.” But given that the starting point is indeterminate, then moving onward must mean determining. Only during the course of the movement of presentation does that from which I start come to determine and manifest itself. Hence, progression is at the same time retrogression – I return whence I started. In retrogression I retract progression; i.e., temporalization of thought: I restore the lost identity. But the first principle to which I return is no longer the initial, indeterminate, and unproved first principle; it is now mediated and therefore no longer the same or, even granting that it is the same, no longer in the same form. This process is of course well founded and necessary, although it rests only on the relationship of self-manifesting and self-presenting thought to thought in itself; i.e., to inner thought. Let us put it in the following way. I read the Logic of Hegel from beginning to end. At the end I return to the beginning. The idea of the Idea or the Absolute Idea contains in itself the idea of Essence, the idea of Being. I therefore know now that Being and Essence are moments of the Idea, or that the Absolute Idea is the Logic in nuce. (Of course, at the end I return to the beginning, but, let us hope, not in time, that is, not in a way that would make me begin with the Logic all over again;[1] for otherwise I would be necessitated to go the same way a second and a third time and so on with the result that my whole life will have become a circular movement within the Hegelian Logic. I would rather close the three volumes of the Logic once I have arrived at its end – the Absolute Idea, because I will then know what it contains. In the knowledge that I now have, I cancel the temporal process of mediation; I know that the Absolute Idea is the Whole, and I naturally need time to be able to realize for myself its processual form; however, this order of succession is completely indifferent here. The Logic in three volumes, i.e., the worked-out Logic, is not a goal in itself, for otherwise I would have no other goal in life than to go on reading it or to memorize it as a “paternoster.” Indeed, the Absolute Idea itself retracts its process of mediation, encompasses this process within itself, and nullifies the reality of presentation in that it shows itself to be the first and the last, the one and all. And for this very reason, I, too, now shut the Logic and concentrate its spread into one idea. In the end, the Logic leads us, therefore, back to ourselves, i.e., to our inner act of cognition; mediating and self-constituting knowledge becomes unmediated knowledge, but not unmediated in the subjective sense of Jacobi because there is no unmediated knowledge in that sense. I mean a different kind of unmediatedness.

To the extent to which it is self-activity, thinking is an unmediated activity. No one else can think for me; only through myself do I convince myself of the truth of a thought. Plato is meaningless and non-existent for someone who lacks understanding; he is a blank sheet to one who cannot link ideas that correspond with his words. Plato in writing is only a means for me; that which is primary and a priori, that which is the ground to which all is ultimately referred, is understanding. To bestow understanding does not lie in the power of philosophy, for understanding is presupposed by it; philosophy only shapes my understanding. The creation of concepts on the basis of a particular kind of philosophy is not a real but only a formal creation; it is not creation out of nothing, but only the development, as it were, of a spiritual matter lying within me that is as yet indeterminate but, nevertheless, capable of assuming all determinations. The philosopher produces in me only the awareness of what I can know; he fastens on to my mental ability. In this sense, philosophy, issuing either from the mouth or the pen, goes back directly to its own source; it does not speak in order to speak – hence its antipathy against all pretty talk – but in order not to speak, that is, in order to think; it does not demonstrate – hence its contempt for all sophistic syllogistics – but only to show that what it demonstrates is simply in keeping with the very principle of all demonstration and reason, and that it is stringent thought; i.e., a thought that expresses to every thinking person a law of reason. To demonstrate is to show that what I am saying is true, is to lead expressed thought back to its source. The meaning of demonstration cannot, therefore, be grasped without reference to the meaning of language. Language is nothing other than the realization of the species; i.e., the “I” is mediated with the “You” in order, by eliminating their individual separateness, to manifest the unity of the species. Now, the element in which the word exists is air, the most spiritual and general medium of life. A demonstration has its ground only in the mediating activity of thought for others. Whenever I wish to prove something, I do so for others. When I prove, teach, or write, then I do so, I hope, not for myself; for I also know, at least in essentials, what I do not write, teach, and discuss. This is also the reason why one often finds it most difficult to write about something which one knows best, which is so perfectly certain and clear to oneself that one cannot understand why others should not know it as well. A writer who is so certain of the object he is to write about that he would not even take the trouble to write about it falls into a category of humor that is in a class by itself. He defeats the purpose of writing through writing, and jokes about proofs in his proofs. If I am to write and, indeed, write well and in a fundamental way, then I must doubt that the others know what I know, or at least that they know it in the same way as I do. Only because of that can I communicate my thoughts. But I also presuppose that they should and can know them. To teach is not to drum things into a person; rather, the teacher applies himself to an active capacity, to a capacity to learn. The artist presupposes a sense of beauty – he cannot bestow it upon a person – for in order that we take his works to be beautiful, in order that we accept and countenance them at all, he must presuppose in us a sense of art. All he can do is to cultivate it and give it a certain direction. Similarly, the philosopher does not assume that he is a speculative Dalai Lama, that he is the incarnation of reason itself. In order that we recognize his thoughts as true, in order that we understand them at all, he presupposes reason, as a common principle and measure in us as well as in himself. That which he has learned, we should also be able to know, and that which he has found we should also be able to find in ourselves with the help of our own thinking. Demonstration is therefore not a mediation through the medium of language between thought, in so far as it is my thought, and the thought of another person, in so far as it is his thought – where two or three people assemble in my name, I, reason, and truth am there among you – nor is it a mediation of “I” and “You” to know the identity of reason, nor, again, a mediation through which I verify that my thought is not mine, but is rather thought in and for itself so that it can just as well be mine as that of someone else. If we are indifferent in life as to whether our thoughts are understood and acknowledged, then this indifference is shown only to this or that man or to this or that class of men because we regard them as people who are full of prejudices, corrupted by particular interests and feelings, incorrigible. Their number does not matter here at all. It is of course true that man can be self-sufficient because he knows himself to be a whole, because he distinguishes himself from himself, and because he can be the other to himself; man speaks to and converses with himself, and because he knows that his thought would not be his own if it were also not – at least as a possibility – the thought of others. But all this indifference, all this self-sufficiency and self-concern are only exceptional phenomena. In reality, we are not indifferent; the urge to communicate is a fundamental urge – the urge for truth. We become conscious and certain of truth only through the other, even if not through this or that accidental other. That which is true belongs neither to me nor exclusively to you, but is common to all. The thought in which “I” and “You” are united is a true thought. This unification is the confirmation, sign, and affirmation of truth only because it is itself already the truth. That which unites is true and good. The objection that, hence, theft too is true and good, because here, too, men are united, does not deserve to be refuted. In this case, each is only for himself.

All philosophers we know have expressed – i.e., taught – their ideas either orally, like Socrates, or in written form; otherwise they could not have become known to us. To express thoughts is to teach; but to teach is to demonstrate the truth of that which is taught. This means that demonstrating is not just a relationship of the thinker to himself or of a thought that is imprisoned within itself to itself, but the relationship of the thinker to others. Hence, the forms of demonstration and inference cannot be the forms of reasons as such; i.e., forms of an inner act of thought and cognition. They are only forms of communication, modes of expression, representations, conceptions; in short, forms in which thought manifests itself. That is why a quick-witted person can be ahead of his demonstrating teacher; even with the first thought, he anticipates in no time the ensuing sequence of deductions which another person must go through step by step. A genius for thinking is just as much innate to man, and exists just as much to a certain degree in all men – in the form of receptivity – as a genius for art. The reason why we regard the forms of communication and expression as the basic forms of reason and thought lies in the fact that, in order to raise them to the clarity of consciousness, we present our fundamental thoughts to ourselves in the same way as we present them to another person, that we first teach ourselves these fundamental thoughts which directly spring from our genius for thinking – they come to us we know not how – and which are perhaps innate to our being. In short, the reason lies in the fact that we express and articulate our thoughts in thought itself. Demonstrating is therefore only the means through which I strip my thought of the form of “mine-ness” so that the other person may recognize it as his own. Demonstrating would be senseless if it were not also communicating. However, the communicating of thoughts is not material or real communication. For example, a push, a sound that shocks my ears, or light is real communication. I am only passively receptive to that which is material; but I become aware of that which is mental only through myself, only through self-activity. For this very reason, what the person demonstrating communicates is not the subject matter itself, but only the medium; for he does not instil his thoughts into me like drops of medicine, nor does he preach to deaf fishes like Saint Francis; rather, he addresses himself to thinking beings. The main thing – the understanding of the thing involved – he does not give me; he gives nothing at all – otherwise the philosopher could really produce philosophers, something which so far no one has succeeded in achieving. Rather, he presupposes the faculty of understanding; he shows me – i.e., to the other person as such – my understanding only in a mirror. He is only an actor; i.e., he only embodies and represents what I should reproduce in myself in imitation of him. Self-constituting and systematic philosophy is dramatic and theatrical philosophy as opposed to the poetry of introspective material thought. The person demonstrating says and points out to me: “This is rational, this is true, and this is what is meant by law; this is how you must think when you think truly.” To be sure, he wants me to grasp and acknowledge his ideas, but not as his ideas; he wants me to grasp them as generally rational; i.e., also as mine. He only expresses what is my own understanding. Herein lies the justification for the demand that philosophy should awaken, stimulate thought, and not make us the captives of its oral or written word – a communicated thought is precisely thought externalized into word – which always has a mentally deadening effect. Every presentation of philosophy, whether oral or written, is to be taken and can only be taken in the sense of a means. Every system is only an expression or image of reason, and hence only an object of reason, an object which reason – a living power that procreates itself in new thinking beings – distinguishes from itself and posits as an object of criticism. Every system that is not recognized and appropriated as just a means, limits and warps the mind for it sets up the indirect and formal thought in the place of the direct, original, and material thought. It kills the spirit of invention; it makes it impossible to distinguish the spirit from the letter for together with the thought – herein lies the limitation of every system as something external – it also necessarily insists on retaining the word, thus failing to capture, indeed denying completely the original meaning and determination of every system and expression of thought. All presentation, all demonstration – and the presentation of thought is demonstration – has, according to its original determination – and that is all that matters to us – the cognitive activity of the other person as its ultimate aim.

Moreover, it is quite obvious that presentation or demonstration is also an end for itself, since every means must, in the first instance, be an end. The form must itself be instructive, that is, objectively expressed. The presentation of philosophy must itself be philosophical – the demand for the identity of form and content finds herein its justification. The presentation is, of course, systematic to the extent to which it is itself philosophical. By virtue of being so, the presentation comes to have a value in and for itself. For that reason the systematizer is an artist – the history of philosophical system is the picture gallery of reason. Hegel is the most accomplished philosophical artist, and his presentations, at least in part, are unsurpassed models of scientific art sense and, due to their rigor, veritable means for the education and discipline of the spirit. But precisely because of this, Hegel – in keeping with a general law which we cannot discuss here – made form into essence, the being of thought for others into being in itself, the relative goal into the final goal. Hegel, in his presentation, aimed at anticipating and imprisoning the intellect itself and compressing it into the system. The system was supposed to be, as it were, reason itself; all immediate activity was to dissolve itself completely in mediated activity, and the presentation of philosophy was not to presuppose anything, that is, nothing was to be left over in us and nothing within us – a complete emptying of ourselves. The Hegelian system is the absolute self-externalization of reason, a state of affairs that expresses itself, among other things, in the fact that the empirical character of his natural law is pure speculation. The true and ultimate reason for all complaints about formalism, neglect of subjectivity, etc., lies solely in the fact that Hegel compresses everything into his presentation, that he proceeds abstractly from the pre-existence of the intellect, and that he does not appeal to the intellect within us. It is true that Hegel retracts the process of mediation in what he calls the result, but in so far as form is posited as objective essence, one is again left in doubt as to the objectivity or subjectivity of the process of mediation. Hence, those who claim that the process of the mediation of the Absolute is only a formal one may well be materially right, but those who claim the opposite, that is, those who claim objective reality for this process, may not, at least formally, be in the wrong.

The Hegelian philosophy is thus the culminating point of all speculative-systematic philosophy. With this, we have discovered and mooted the reason underlying the beginning of the Logic. Everything is required either to present (prove) itself or to flow into, and be dissolved in, the presentation. The presentation ignores that which was known before the presentation: It must make an absolute beginning. But it is precisely here that the limits of the presentation manifest themselves immediately. Thought is prior to the presentation of thought. That which constitutes the starting point within the presentation is primary only for the presentation but not for thought. The presentation needs thought which, although always present within thinking, emerges only later.[2] The presentation is that which is mediated in and for itself; what is primary is therefore never immediate even within the presentation, but only posited, dependent, and mediated, in that it is determined by the determinations of thought whose certainty is self-dependent and which are prior to and independent of a philosophy presenting and unfolding itself in time. Thus, presentation always appeals to a higher authority – and one which is a priori in relation to it. Who would think that this is not also the case with the “being” of the Hegelian Logic? “Being is that which is immediate, indeterminate, self-same, self-identical, and undifferentiated.” But are not the notions of immediacy and identity presupposed here? “Being merges into Nothingness; it disappears immediately into its opposite: its truth is the very movement of its disappearing.” Does Hegel not take perceptions for granted here? Is disappearing a notion or is it rather a sensuous perception? “Becoming is restlessness, the restless unity of being and nothingness; existence is this unity having come to rest.” Is not a highly doubtful perception simply taken for granted here? Can a skeptic not object that rest is a sensory illusion, that everything is rather in constant motion? What, therefore, is the use of putting such ideas at the starting point, even if only as images? But it may be objected that such assumptions as the notions of sameness and identity are quite evident and natural. How else could we conceive of being? These notions are the necessary means through which we cognize being as primary. Quite right! But is being, at least for us, immediate? Is it not rather that wherefrom we cannot abstract the Primary? Of course, the Hegelian philosophy is aware of this as well. Being, whence the Logic proceeds, presupposes on the one hand the Phenomenology, and on the other, the Absolute Idea. Being (that which is primary and indeterminate) is revoked in the end as it turns out that it is not the true starting point. But does this not again make a Phenomenology out of the Logic? And being only a phenomenological starting point? Do we not encounter a conflict between appearance and truth within the Logic as well? Why does Hegel not proceed from the true starting point? “Indeed, the true can only be a result; the true has to prove itself to be so, that is, it has to present itself.” But how can it do so if being itself has to presuppose the Idea, that is, when the Idea has already in itself been presupposed as the Primary? Is this the way for philosophy to constitute and demonstrate itself as the truth so that it can no longer be doubted, so that skepticism is reduced once and for all to absurdity? Of course, if you say A, you will also have to say B. Anyone who can countenance being at the beginning of the Logic will also countenance the Idea; if this being has been accepted as proved by someone, then he must also accept the Idea as proved. But what happens if someone is not willing to say A? What if he says instead, “Your indeterminate and pure being is just an abstraction to which nothing real corresponds, for real is only real being? Or else prove if you can the reality of general notions!” Do we not thus come to those general questions that touch upon the truth and reality not only of Hegel’s Logic but also of philosophy altogether? Is the Logic above the dispute between the Nominalists and Realists (to use old names for what are natural contraries)? Does it not contradict in its first notions sense perception and its advocate, the intellect? Have they no right to oppose the Logic? The Logic may well dismiss the voice of sense perception, but, then, the Logic itself is dismissed by the intellect on the ground that it is like a judge who is trying his own case. Have we therefore not the same contradiction right at the outset of the philosophical science as in the philosophy of Fichte? In the latter case, the contradiction is between the pure and the empirical, real ego; in the former, it is between the pure and the empirical, real being. “The pure ego is no longer an ego”; but, then, the pure and empty being, too, is no longer being. The Logic says: “I abstract from determinate being; I do not predicate of determinate being the unity of being and nothingness.” When this unity appears to the intellect as paradoxical and ridiculous it quickly substitutes determinate being by pure being, for now it would, of course, be a contradiction for being not to be nothingness as well. But the intellect retorts: “Only determinate being is being; in the notion of being lies the notion of absolute determinateness. I take the notion of being from being itself; however, all being is determinate being – that is why, in passing, I can also posit nothingness which means ‘not something’ or ‘opposed to being’ because I always and inseparably connect ‘something’ with being. If you therefore leave out determinateness from being, you leave being with no being at all. It will not be surprising if you then demonstrate that indeterminate being is nothingness. Under these circumstances this is self-evident. If you exclude from man that which makes him man, you can demonstrate without any difficulty whatsoever that he is not man. But just as the notion of man from which you have excluded the specific difference of man is not a notion of man, but rather of a fabricated entity as, for example, the Platonic man of Diogenes, so the notion of being from which you have excluded the content of being is no longer the notion of being. Being is diverse in the same measure as things. Being is one with the thing that is. Take away being from a thing, and you take away everything from it. It is impossible to think of being in separation from specific determinations. Being is not a particular notion; to the intellect at least, it is all there is.”

Therefore, how can the Logic, or any particular philosophy at all, reveal truth and reality if it begins by contradicting sensuous reality and its understanding without resolving this contradiction? That it can prove itself to be true is not a matter of doubt; this, however, is not the question. A twosome is needed to prove something. While proving, the thinker splits himself into two; he contradicts himself, and only after a thought has been and has overcome its own opposition, can it be regarded as proved. To prove is at the same time to refute. Every intellectual determination has its antithesis, its contradiction. Truth exists not in unity with, but in refutation of its opposite. Dialectics is not a monologue that speculation carries on with itself, but a dialogue between speculation and empirical reality. A thinker is a dialectician only in so far as he is his own opponent. The zenith of art and of one’s own power is to doubt oneself. Hence, if philosophy or, in our context, the Logic wishes to prove itself true, it must refute rational empiricism or the intellect which denies it and which alone contradicts it. Otherwise all its proofs will be nothing more than subjective assurances, so far as the intellect is concerned. The antithesis of being – in general and as regarded by the Logic – is not nothingness, but sensuous and concrete being.

Sensuous being denies logical being; the former contradicts the latter and vice versa. The resolution of this contradiction would be the proof of the reality of logical being, the proof that it is not an abstraction, which is what the intellect now takes it to be.

The only philosophy that proceeds from no presuppositions at all is one that possesses the courage and freedom to doubt itself, that produces itself out of its antithesis. All modern philosophies, however, begin only with themselves and not with what is in opposition to them. They presuppose philosophy; that is, what they understand by philosophy to be the immediate truth. They understand by mediation only elucidation, as in the case of Fichte, or development, as in the case of Hegel. Kant was critical towards the old metaphysics, but not towards himself. Fichte proceeded from the assumption that the Kantian philosophy was the truth. All he wanted was to raise it to “science,” to link together that which in Kant had a dichotomized existence, by deriving it from a common principle. Similarly, Schelling proceeded from the assumption that the Fichtean philosophy was the established truth, and restored Spinoza in opposition to Fichte. As far as Hegel is concerned, he is a Fichte as mediated through a Schelling. Hegel polemicized against the Absolute of Schelling; he thought it lacked the moment of reflection, apprehension, and negativity. In other words, he imbued the Absolute Identity with Spirit, introduced determinations into it, and fructified its womb with the semen of the Notion (the ego of Fichte). But he, nevertheless, took the truth of the Absolute for granted. He had no quarrel with the existence or the objective reality of Absolute Identity; he actually took for granted that Schelling’s philosophy was, in its essence, a true philosophy. All he accused it of was that it lacked form. Hence, Hegel’s relationship to Schelling is the same as that of Fichte to Kant. To both the true philosophy was already in existence, both in content and substance; both were motivated by a purely “scientific,” that is, in this case, systematic and formal interest. Both were critics of certain specific qualities of the existing philosophy, but not at all of its essence. That the Absolute existed was beyond all doubt. All it needed was to prove itself and be known as such. In this way it becomes a result and an object of the mediating Notion; that is, a “scientific” truth and not merely an assurance given by intellectual intuition.

But precisely for that reason the proof of the Absolute in Hegel has, in principle and essence, only a formal significance, notwithstanding the scientific rigor with which it is carried out. Right at its starting point, the philosophy of Hegel presents us with a contradiction, the contradiction between truth and science, between essence and form, between thinking and writing. The Absolute Idea is assumed, not formally, to be sure, but essentially. What Hegel premises as stages and constituent parts of mediation, he thinks are determined by the Absolute Idea. Hegel does not step outside the Idea, nor does he forget it. Rather, he already thinks the antithesis out of which the Idea should produce itself on the basis of its having been taken for granted. It is already proved substantially before it is proved formally. Hence, it must always remain unprovable, always subjective for someone who recognizes in the antithesis of the Idea a premise which the Idea has itself established in advance. The externalization of the Idea is, so to speak, only a dissembling; it is only a pretense and nothing serious – the Idea is just playing a game. The conclusive proof is the beginning of the Logic, whose beginning is to be taken as the beginning of philosophy as such. That the starting point is being is only a formalism, for being is here not the true starting point, nor the truly Primary. The starting point could just as well be the Absolute Idea because it was already a certainty, an immediate truth for Hegel before he wrote the Logic; i.e., before he gave a scientific form of expression to his logical ideas. The Absolute Idea – the Idea of the Absolute – is its own indubitable certainty as the Absolute Truth. It posits itself in advance as true; that which the Idea posits as the other, again presupposes the Idea according to its essence. In this way, the proof remains only a formal one. To Hegel, the thinker, the Absolute Idea was absolute certainty, but to Hegel, the author, it was a formal uncertainty. This contradiction between the thinker who is without needs, who can anticipate that which is yet to be presented because everything is already settled for him, and the needy writer who has to go through a chain of succession and who posits and objectifies as formally uncertain what is certain to the thinker – this contradiction is the process of the Absolute Idea which presupposes being and essence, but in such a way that these on their part already presuppose the Idea. This is the only adequate reason required to explain the contradiction between the actual starting point of the Logic and its real starting point which lies at the end. As was already pointed out, Hegel in his heart of hearts was convinced of the certainty of the Absolute Idea. In this regard, there was nothing of the critic or the skeptic in him. However, the Absolute Idea had to demonstrate its truth, had to be released from the confines of a subjective intellectual conception – it had to be shown that it also existed for others. Thus understood, the question of its proof had an essential, and at the same time an inessential, meaning: It was a necessity in so far as the Absolute Idea had to prove itself, because only so could it demonstrate its necessity; but it was at the same time superfluous as far as the inner certainty of the truth of the Absolute Idea was concerned. The expression of this superfluous necessity, of this dispensable indispensability or indispensable dispensability is the Hegelian method. That is why its end is its beginning and its beginning its end. That is why being in it is already the certainty of the Idea, and nothing other than the Idea in its immediacy. That is why the Idea’s lack of self-knowledge in the beginning is, in the sense of the Idea, only an ironical lack of knowledge. What the Idea says is different from what it thinks. It says “being” or “essence,” ‘but actually it thinks only for itself. Only at the end does it also say what it thinks, but it also retracts at the end what it had expressed at the beginning, saying: “What you had, at the beginning and successively, taken to be a different entity, that I am myself.” The Idea itself is being and essence, but it does not yet confess to be so; it keeps this secret to itself.

That is exactly why, to repeat myself, the proof or the mediation of the Absolute Idea is only a formal affair. The Idea neither creates nor proves itself through a real other – that could only be the empirical and concrete perception of the intellect. Rather, it creates itself out of a formal and apparent antithesis. Being is in itself the Idea. However, to prove cannot mean anything other than to bring the other person to my own conviction. The truth lies only in the unification of “I” and “You.” The Other of pure thought, however, is the sensuous intellect in general. In the field of philosophy, proof therefore consists only in the fact that the contradiction between sensuous intellect and pure thought is disposed, so that thought is true not only for itself but also for its opposite. For even if every true thought is true only through itself, the fact remains that in the case of a thought that expresses an antithesis, its credibility will remain subjective, one-sided, and doubtful so long as it relies only on itself. Now, logical being is in direct, unmediated, and abhorrent contradiction with the being of the intellect’s empirical and concrete perception. In addition, logical being is only an indulgence, a condescension on the part of the Idea, and, consequently, already that which it must prove itself to be. This means that I enter the Logic as well as intellectual perception only through a violent act, through a transcendent act, or through an immediate break with real perception. The Hegelian philosophy is therefore open to the same accusation as the whole of modern philosophy from Descartes and Spinoza onward – the accusation of an unmediated break with sensuous perceptions and of philosophy’s immediate taking itself for granted.[3]

The Phenomenology cannot be seen as invalidating this accusation, because the Logic comes after it. Since it constitutes the antithesis of logical being it is always present to us, it is even necessarily brought forth by the antithesis and provoked by it to contradict the Logic, all the more so because the Logic is a new starting point, or a beginning from the very beginning, a circumstance which is ab initio offensive to the intellect. But let us grant the Phenomenology a positive and actual meaning in relation to the Logic. Does Hegel produce the Idea or thought out of the other-being of the Idea or thought? Let us look at it more closely. The first chapter deals with “Sensuous Certainty, the This and Meaning.” It designates that stage of consciousness where sensuous and particular being is regarded as true and real being, but where it also suddenly reveals itself as a general being. “The ‘here’ is a tree”; but I walk further and say: “The ‘here’ is a house.” The first truth has now disappeared. “The ‘now’ is night,” but it is not long before “the ‘now’ is day.” The first alleged truth has now become “stale.” The “now” therefore comes out to be a general “now,” a simple (negative) manifold. The same is the case with “here.” “The ‘here’ itself does not disappear, but remains in the disappearance of the house, tree, and so on, and is indifferent to being the house, tree, etc. Therefore, this shows itself again as mediated simplicity or generality.” The particular which we mean in the context of sensuous certainty is something we cannot even express. “Language is more truthful; here, we ourselves directly cancel our opinions, and, since it is the general which is true in sensuous certainty and which alone is expressed by language, we cannot possibly express a sensuous entity as intended.” But is this a dialectical refutation of the reality of sensuous consciousness? Is it thereby proved that the general is the real? It may well be for someone who is certain in advance that the general is the real, but not for sensuous consciousness or for those who occupy its standpoint and will have to be convinced first of the unreality of sensuous being and the reality of thought. My brother is called John, or, if you like, Adolph, but there are innumerable people besides him who are called by the same name. Does it follow from this that my brother John is not real? Or that Johnness is the truth? To sensuous consciousness, all words are names – nomina propria. They are quite indifferent as far as sensuous consciousness is concerned; they are all signs by which it can achieve its aims in the shortest possible way. Here, language is irrelevant. The reality of sensuous and particular being is a truth that carries the seal of our blood. The commandment that prevails in the sphere of the senses is: An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. Enough of words, come down to real things! Show me what you are talking about! To sensuous consciousness it is precisely language that is unreal, nothing. How can it regard itself, therefore, as refuted if it is pointed out that a particular entity cannot be expressed in language? Sensuous consciousness sees precisely in this a refutation of language but not a refutation of sensuous certainty. And it is perfectly justified, too, because otherwise we would have to feed ourselves on mere words instead of on things in life. The content of the whole first chapter of the Phenomenology is, therefore, for sensuous consciousness nothing but the reheated cabbage of Stilpo the Megarian – only in the opposite sense. It is nothing but a verbal game in which thought that is already certain of itself as truth plays with natural consciousness. Consciousness, however, does not let itself be confounded; it holds firmly to the reality of individual things. Why just the “here” and not “that which is here?” Why just the “now” and not “that which is now?” In this way, the “here” and the “now” will never become a mediated and general “here,” a mediated and general “now” for sensuous consciousness or for us who are its advocates and wish to be convinced of something better and different. Today is now, but tomorrow is again now, and it is still completely the same unchanged and incorrigible now as it was yesterday. Here is a tree, there a house, but when there, I again say “here”; the “here” always remains the old “everywhere” and “nowhere.” A sensuous being, a “this,” passes away, but there comes another being in its place which is equally a “this.” To be sure, nature refutes this individual, but it soon corrects itself. It refutes the refutation in that it puts another individual in place of the previous one. Hence, to sensuous consciousness it is sensuous being that lasts and does not change.

The same unmediated contradiction, the same conflict that we encounter at the beginning of the Logic now confronts us at the beginning of the Phenomenology – the conflict between being as the object of the Phenomenology and being as the object of sensuous consciousness. The “here” of the Phenomenology is in no way different from another “here” because it is actually general. But the real “here” is distinguished from another “here” in a real way; it is an exclusive “here.” “This ‘here’ is, for example, a tree. I turn around and this truth has disappeared.” This can, of course, happen in the Phenomenology where turning around costs nothing but a little word. But, in reality, where I must turn my ponderous body around, the “here” proves to be a very real thing even behind my back. The tree delimits my back and excludes me from the place it already occupies. Hegel does not refute the “here” that forms the object of sensuous consciousness; that is, an object f or us distinct from pure thought. He refutes only the logical “here,” the logical “now.” He refutes the idea of “this-being,” haecceitas. He shows the untruth of an individual being in so far as it is determined as a (theoretical) reality in imagination. The Phenomenology is nothing but a phenomenological Logic. Only from this point of view can the chapter on sensuous certainty be excused. However, precisely because Hegel did not really immerse himself in sensuous consciousness, did not think his way into it because in his view sensuous consciousness is an object in the sense of an object of self-consciousness or thought; because self-consciousness is merely the externalization of thought within the self-certainty of thought; so the Phenomenology or the Logic – both have the same thing in common – begins with itself as its own immediate presupposition, and hence with an unmediated contradiction, namely, with an absolute break with sensuous consciousness. ‘For it begins, as mentioned already, not with the “other-being” of thought, but with the idea of the “other-being” of thought. Given this, thought is naturally certain of its victory over its adversary in advance. Hence, the humor with which thought pulls the leg of sensuous consciousness. But this also goes to show that thought has not been able to refute its adversary.

Quite apart from the significance of the Phenomenology, Hegel started, as was already mentioned, from the assumption of Absolute Identity right from the earliest beginnings of his philosophical activity. The idea of Absolute Identity, or of the Absolute, was simply an objective truth for him. It was not just a truth for him, but absolute truth, the Absolute Idea itself – absolute, that is, beyond all doubt and above all criticism and skepticism. But the idea of the Absolute was, according to its positive meaning, at the same time only the idea of objectivity in opposition to the idea of subjectivity, as in the Kantian and Fichtean philosophy. For that reason, we must understand the philosophy of Schelling not as “absolute” philosophy – as it was to its adherents – but as the antithesis of critical philosophy. As we know, Schelling wanted in the beginning to go in an opposite direction to idealism. His natural philosophy was actually reversed idealism at first, which means that a transition from the latter to the former was not difficult. The idealist philosopher sees life and reason in nature also, but he means by them his own life and his own reason. What he sees in nature is what he puts into it; what he gives to nature is therefore what he takes back into himself – nature is objectified ego, or spirit looking at itself as its own externalization. Idealism, therefore, already meant the unity of subject and object, spirit and nature, but together with the implication that in this unity nature had only the status of an object; that is, of something posited by spirit. The problem was, therefore, only to release nature from the bondage to which the idealist philosopher had subjected it by chaining it to his own ego, to restore it to an independent existence in order to bestow upon it the meaning it received in the philosophy of nature. The idealist said to nature, “You are my alter ego,” while he emphasized only the ego so that what he actually meant was: “You are an outflow, a reflected image of myself, but nothing particular just by yourself.” The philosopher of nature said the same thing, but he emphasized the “alter”: “To be sure, nature is your ego, but your other ego, and hence real in itself and distinguished from you.” That is why the meaning of the identity of spirit and nature was also a purely idealistic one in the beginning. “Nature is only the visible organism of our intellect” (Schelling, in the Introduction to the Project for a System of the Philosophy of Nature.) “The organism is itself only a mode of perception of the intellect.” (Schelling, in The System of Transcendental Idealism.) “It is obvious that the ego constructs itself while constructing matter... . This product – matter – is therefore completely a construction by the ego, although not for an ego that is still identical with matter.” (Ibid.) “Nature shall be the visible spirit, and spirit, invisible nature.” (Schelling, in the Introduction to Ideas for a Philosophy of Nature.) The philosophy of nature was supposed to begin only from what is objective, but at the same time to arrive at the same result at which idealism arrived through and out of itself. “The necessary tendency of all natural science is to arrive at the intellect from nature.” (Schelling, in The System of Transcendental Idealism.) “The task of the philosophy of nature is to show the primacy of the objective and to derive the subjective from it! All philosophy must strive either to produce the intellect out of nature or nature out of the intellect” (Ibid.) That is why the philosophy of nature, with all its integrity, left idealism undisturbed, for all it wanted was to demonstrate a posteriori what idealism had said of itself a priori. The only difference between the two lay in the course taken, in method. Nevertheless, basic to the opposite course, there was an opposite intuition, or at least it had to emerge unavoidably from this opposite course. It was bound to happen that nature thus received a meaning for itself. The object had already been released from the confines of subjective idealism in so far as it had also been posited as the object of a particular science. If not in itself, nature was nevertheless not something derivative or posited for natural science, but rather something primary and independent. In this way, nature received a meaning that was opposed to the idealism of Fichte. But even so the meaning which nature had in and for idealism – that is, one which was diametrically opposed to the meaning of nature in the philosophy of nature – was to retain its validity as if nothing had happened, and idealism was to continue to exist undiminished and with all its rights and pretensions. Consequently, we now have two independent and mutually opposed truths instead of the only absolutely decisive and autonomous truth of the Fichtean ego – the truth of idealism, which denies the truth of the philosophy of nature, and the truth of the philosophy of nature, which in its turn denies the truth of idealism.[4] For the philosophy of nature it is nature alone that exists, just as for idealism it is only spirit. For idealism, nature is only object and accident, but for the philosophy of nature it is substance, i.e., both subject and object, something which only intelligence within the context of idealism claims to be. However, two truths, two “Absolutes,” is a contradiction. How do we find a way out of this conflict between a philosophy of nature that negates idealism and an idealism that negates the philosophy of nature? Only by turning the predicate wherein both concur into the subject – this would then be the Absolute or that which is purely and simply independent – and the subject into the predicate. In other words, the Absolute is nature and spirit. Spirit and nature are only predicates, determinations, forms of one and the same thing; namely, of the Absolute. But what then is the Absolute? Nothing other than this “and,” that is, the unity of spirit and nature. But are we really making any progress in taking this step? Did we not have this unity already in the notion of nature? For the philosophy of nature is a science not of an object that is opposed to the “I,” but of an object that is itself both subject and object – the philosophy of nature is at the same time idealism. Further, the connection between the notions of subject and object within the notion of nature was precisely the supersession of the separation – effected by idealism – between mind and non-mind, hence the supersession of the separateness of nature and spirit. What is it, therefore, through which the Absolute distinguishes itself from nature? The Absolute is the Absolute Identity, the absolute subject-object, whereas mind is the subjective subject-object. Oh, what brilliance! And how surprising! Suddenly, we find ourselves on the standpoint of idealistic dualism: We deprive nature at the same time of that which we give it. Nature is the subject-object with the plus of objectivity. That means that the positive notion of nature – provided that the plus gives us a notion whereby nature is not suspended into the vacuum of the Absolute, but still remains nature – is that of objectivity; and similarly the notion of the spirit – in so far as it is spirit – is not a vague, nameless entity, but the notion of subjectivity in as much as the plus of subjectivity constitutes its distinguishing feature. But are we the cleverer for this approach than we were initially? Do we not have to bear again the same old cross of subjectivity and objectivity? If the Absolute is now cognized, that is, if it is brought out of the darkness of absolute indeterminateness where it is only an object of imagination and phantasy into the light of the notion, then it is cognized either as spirit or as nature. Hence, there is no science of the Absolute as such, but either the science of the Absolute as nature or that of the Absolute as spirit; that is, either the philosophy of nature or of idealism, or if both together, then only in such a way that the philosophy of nature is only the philosophy of the Absolute as nature, while idealism is only the philosophy of the Absolute as spirit. But if the object of the philosophy of nature is the Absolute as nature, then the positive notion is just the notion of nature, which means that the predicate again becomes the subject and the subject – the Absolute – becomes a vague and meaningless predicate. Hence, I could just as well delete the Absolute from the philosophy of nature, for the Absolute applies equally to spirit as to nature; as much to one particular object as to another opposite object; as much to light as to gravity. In the notion of nature, the Absolute as pure indeterminateness, as nihil negativum, disappears for me, or if I am unable to banish it from my head, the consequence is that nature vanishes before the Absolute. That is also the reason why the philosophy of nature did not succeed in achieving anything more than evanescent determinations and differences which are in truth only imaginary, only ideas of distinctions but not real determinations of knowledge.

But precisely for that reason the positive significance of the philosophy of Schelling lies solely in his philosophy of nature compared to the limited idealism of Fichte, which knows only a negative relationship to nature. There-fore, one need not be surprised that the originator of the philosophy of nature presents the Absolute only from its real side, for the presentation of the Absolute from its ideal side had already occurred in Fichteanism before the philosophy of nature. Of course, the philosophy of identity restored a lost unity, but not by objectifying this unity as the Absolute, or as an entity common to and yet distinguished from nature and spirit – for thus understood, the Absolute was only a mongrel between idealism and the philosophy of nature, born out of the conflict between idealism and the philosophy of nature as experienced by the author of the latter – but only in so far as the notion of this unity meant the notion of nature as both subject and object implying the restoration of nature to its proper place.

However, by not being satisfied with its rejection of subjective idealism – this was its positive achievement – and by wanting itself to acquire the character of absolute philosophy, which involved a misconception of its limits, the philosophy of nature came to oppose even that which was positive in idealism. Kant involved himself in a contradiction – something necessary for him but which cannot be discussed here – in so far as he misconceived the affirmative, rational limits of reason by taking them to be boundaries. Boundaries are arbitrary limits that are removable and ought not to be there. The philosophy of identity even rejected the positive limits of reason and philosophy together with these boundaries. The unity of thought and being it claimed to have achieved was only the unity of thought and imagination. Philosophy now became beautiful, poetic, soulful, romantic, but for that matter also transcendent, superstitious, and absolutely uncritical. The very condition of all criticism – the distinction between “subjective” and “objective” – thus melted into thin air. Discerning and determining thought came to be regarded as a finite and negative activity. No wonder then that the philosophy of identity finally succumbed, irresistibly and uncritically, to the mysticism of the Cobbler of Görlitz.