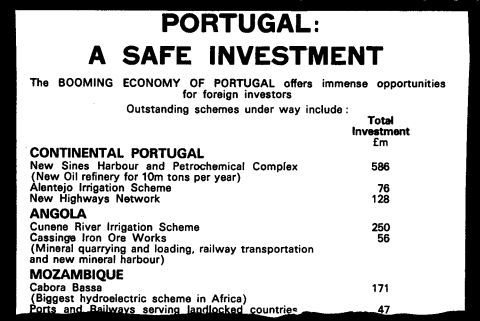

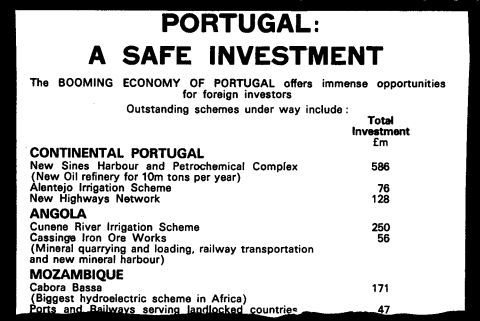

‘A safe investment’ – an advert in the Economist in February shows

the extent of Portugal’s foreign investments

Ian Birchall Archive | ETOL Main Page

From International Socialism (1st series), No.69, May 1974, pp.15-18.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

|

THE IMPORTANCE of developments in Portugal since the April coup can hardly be exaggerated. The situation has gone far beyond what was envisaged by those who made the coup. In the process a question mark is being put over not only the future of Portugal itself, but also the futures of its Spanish neighbour in the Iberian peninsula and of the whole of Southern Africa. The outcome of the present upheaval in Portugal will be of decisive international significance. |

Exactly how events are going to turn out in the weeks and months ahead is still unclear. But these events can only be understood against the background of a deep rooted crisis in Portuguese society.

THE ECONOMIC basis of the ruling class has been undergoing substantial changes in the last 20 years. The economy remains the most backward in Europe, with output per head at only two thirds the Spanish level. But some industrial development has been taking place, gradually changing Portugal from an overwhelmingly agricultural country to one where industry plays an important role. In 1950 half the population lived off the land (in agriculture, fishing or forestry) and only a quarter worked in industry; by the late 1960s the proportion in industry had risen to 35.5 per cent and that in agriculture fallen to 33.5 per cent.

This change has been based upon a massive inflow of foreign capital into Portugal and the Portuguese African colonies. There are 200 companies in Portugal associated with British capital, with total investments of £300 million. They include Plesseys, GEC, Babcock and Wilcox, British Leyland, BICC, British Steel Corporation, Rootes-Chrysler and Metal Box. Other international companies, notably ITT, are also there.

|

|

‘A safe investment’ – an advert in the Economist in February shows |

Their aim is to exploit the low-paid labour of the Portuguese working class. In Lisbon, the capital, the average wage for a 45 hour week is between £7 and £10; elsewhere wages are even lower. In some districts infant mortality is as high as 10 per cent and the Portuguese have the lowest life expectancy in Europe. Low wages in Portugal have been directly responsible for unemployment in Britain as production has been shifted.

In the 1972 Plessey annual report Sir John Clark noted that ‘significant contributions to profits continue to come from South Africa and Portugal’; at the same time he regretted the ‘need’ for rationalisation and closures in Britain.

But Portugal has faced grave social and economic problems for some time. Firstly, the problem of inflation has been even more acute than elsewhere in Europe – last year inflation reached 21 per cent, and the projected figure for 1974 is 25 per cent.

Secondly, there has been massive emigration from Portugal. There are two million Portuguese workers employed abroad (as against a population of eight and a half million in Portugal); they are seeking better wages and avoiding military service. As a result there are serious labour shortages inside Portugal; for example, all public building work in Lisbon is now being done by immigrants to Portugal from the Cape Verde Islands.

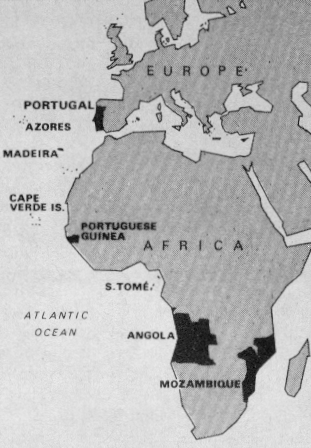

And overshadowing everything has been the problem of the continuing wars in Africa. The African colonies used to be a massive source of wealth for the Portuguese ruling class and the foreign capitalists, chiefly British, who they worked with. While Portugal itself was a backward, agricultural country, the tight-knit ruling oligarchy ran the third biggest empire in the world.

|

But rebellions in Guinea, Angola and Mozambique in the 1960s pushed the cost of maintaining the empire ever upwards. Military expenditure rose from one fifth of the budget in 1960 to more than 43 per cent today.

Such scale of arms spending has made impossible any attempt to deal with the grave social problems that face the majority of the Portuguese people. More importantly for the ruling class, it has prevented the expansion of Portuguese industry keeping up in any way with that in the rest of Europe.

As the Economist pointed out two years ago:

‘Many of the bright young men rising to prominence in the banks and the economic ministries are ready to argue very strongly that the price of holding on to Africa has been the diversion of investment funds from vital development projects in the home country.’ (26 February 1972)

THE COUP finally came when some of Portugal’s biggest monopolies decided that the time had come to change course. One of these, Champalimaud, which controls banks and the steel industry, had for some time followed a ‘liberal’ line, reflecting the fact that it was more closely linked with European capitalism than with African investment. Champalimaud was closely linked with a group of foreign trained technocrats who had had some influence in the early years of the Caetano regime. They were closely associated with the journal Expresso, which advocated a policy of reforms and liberalisation. Also associated with them was the former Education Minister Veiga Simao (a graduate of Manchester and Cambridge Universities) who had begun the reform of Portugal’s archaic education system by developing technical and vocational education.

Shortly before the coup another of the big monopolies, CUF, which owns 10 per cent of Portuguese industrial capacity, moved to a position of opposition to the regime. CUF has many interests in Africa and traditionally has been much more reluctant to consider decolonisation, but recently has been increasingly anxious about the outcome of the colonial wars. It was a firm owned by CUF that published Spinola’s book which advocated a political solution to the African wars.

This recognition of a need for a change of line by the monopolies coincided with the growth of discontent among the army, and in particular the middle-ranking army officers. This discontent had at first been economic in origin; soldiers were badly paid and had to do four years military service. There was a serious shortage of officers, so that many career officers had done several tours of duty in the colonies, and reservists up to the age of 36 were being recalled for service. Many workers of military age emigrated rather than serve; it is estimated that there were over 100,000 draft dodgers throughout Europe.

The discontent in the army was growing even though the Caetano government had recently increased pay; there had been demonstrations in the Military Academy. More and more the demand for economic improvements was spilling over into the demand for an end to the colonial wars.

At home too there was considerable pressure for an end to the wars; demonstrations had taken place, and there was a significant anti-war movement amongst Catholic priests.

General Spinola was the person best suited to bring together the big monopolies on the one hand, and the captains’ movement in the army on the other. Spinola’s past – as a supporter of Franco and Hitler – hardly gives him credentials as a progressive.

As governor and commander in chief in Guinea-Bissau, Spinola followed a policy described by Dr Manuel Boal, one of the leaders of the liberation movement PAIGC, as ‘systematic terrorism’.

‘He bombed defenceless villages in the liberated zone, destroyed our crops and always burned hayfields at the end of the dry season to prevent us constructing huts for the rain season ... He is a man with blood on his hands and a smile on his face.’

One of his feats was to help in organising the murder of the PAIGC leader Cabral.

Spinola was popular with the army as a general who always led from the front line rather than from a position of safety. At the same time he differed sharply from the traditional crudely racialist approach of Portuguese colonialism; he believed it was necessary to try and win support of the native population. He tried to introduce methods similar to the American ‘Vietnamisation’ programme, and engaged troops in work such as school-building.

When Spinola came to the conclusion that the African wars were unwinnable, he dissociated himself from the Caetano regime. His book, Portugal and the Future, published in February this year, was a bombshell; it was the first time anyone in such a position had admitted that a purely military solution to the African wars was impossible.

Spinola’s actual proposals combined ambiguity with Utopianism. He stopped far short of urging complete independence for the colonial territories, preferring such phrases as a ‘scheme of the plurinational state type’ and ‘federal solution cemented by solidarity’. His hopes that political agreement could be established with the liberation forces were at best naive. Yet in the total dead end that Portuguese imperialism had reached his proposals seemed the best available.

Spinola’s role in the present situation is to act as a skilful manipulator. The ‘captains’ movement’ in the army wants to follow much more radical policies than the big monopolies; Spinola has to try and keep both happy.

SPINOLA’S problem was that he could not implement his programme for satisfying the new needs of Portuguese big business without getting rid of the old regime. And he could not do that without paralysing the repressive forces that had kept the mass of the population in check previously.

Whatever the desires of the most advanced groups of capitalists, whole sections of the Portuguese ruling class continued to benefit from the Caetano regime and from the African war. And most of those who ran the machinery of repression itself could see no future for themselves without Caetano and his policies: they were prepared to direct repression against all those who wanted a change, even army officers acting in the interests of other sections of the ruling class.

This was shown some weeks before the coup, when Spinola was dismissed from his position in the army and those officers who moved in his support were thrown into prison.

Hence the contradiction involved in Spinola’s coup: he was acting in the interests of those same monopolies that had previously built up the machine of mass repression, but to protect the position of his supporters, he had to stop that machine working. The inevitable by-product was that the terror directed at the mass of the population disappeared overnight.

Two years ago, a senior government official told the Economist,

‘Portugal is like a pressure cooker, the lid has been kept on for a very long time and if some fool lets all the steam out at once, the thing will blow up.’

That is exactly what Spinola was forced to do. He had to prevent the exercise of power by the secret police in order to protect his own pro-capitalist supporters. But when he did that, he inadvertently permitted the mass of the population to give expression to all the discontents that had been accumulating for half a century.

In the explosion that followed, a process of radicalisation took place far greater than Spinola intended. He did not aim to dismantle the hated secret police, the PIDE, but that is what has happened as a result of spontaneous mass pressure.

All this confronts Spinola with a basic dilemma. The disruption caused to the state machine during the coup means that he cannot yet rule by direct repression. He depends instead on the popular support which exists for some of the measures with which he is identified.

In particular, the workers, peasants and soldiers who support Spinola see him as the man who is going to end the colonial wars. If he fails to do this, he will not survive politically. Yet the actual process of disentangling Portugal from Africa is going to prove very difficult. Portuguese (and British) big business certainly does not want to write off its massive investments there. But the liberation movements know that it is their own successes that have produced the crisis in Portugal and are unlikely to agree to any compromise formulae. Guinea (but not Cape Verde) may get independence fairly quickly, but Mozambique and especially Angola will prove much more difficult to deal with.

THE SITUATION since the coup has opened up fantastic possibilities for the Portuguese working class. The temporary paralysis of the machinery of repression, the sudden upsurge in the popular movement, the fraternisation between sections of the army and the people, the dilemmas facing the new government, all constitute elements in what could be a pre-revolutionary situation. What is lacking is any effective revolutionary leadership for the working class.

During the years of repression, it was very difficult for any real workers’ movement to develop. Under the fascist constitution of 1933 trade unions were controlled by the state, strikes were illegal and strikers could get several years in jail. Riot police and secret informers combined to suppress any trade union militancy.

When Caetano came to power in 1970, he allowed partially free trade union elections, but retained a government right of veto. In 18 out of 21 unions anti-government lists were elected to the executives. But when one of the strongest unions – the bank employees – led a strike in the Lisbon banks, the whole union executive was replaced by an administrative commission, and the secretary general was jailed. The experiment in liberalisation rapidly came to an end.

Nonetheless, there has been a strong tradition of working class struggle in Portugal over recent years. In January 1969 over 70,000 workers were involved in strike actions. In November the same year the Liznave shipyards were occupied by 5,000 workers, and there have been other occupations of factories threatened with closure. In July 1970 riot police broke up a meeting of Lisbon airport workers discussing a wage increase, killing one worker.

What is missing above all in the present situation is a working class party able to give a political focus to this tradition of struggle and begin to raise the question of working class power.

The only organisation that has real roots in the working class is the Portuguese Communist Party. The other political traditions of the Portuguese working class, such as anarcho-syndicalism, were completely destroyed by the decades of repression. Although the Communist Party suffered heavily from the repression, it maintained its organisation, and has more or less complete political monopoly of the organised left.

The Communist Party’s policy in the present situation seems to be to try to come to an agreement with the Junta, offering its services to keep the working class movement in check in return for political recognition and a place in the provisional government.

In its first statement after the coup the party ‘fervently saluted’ the armed forces which toppled the previous regime and said that it would combat ‘adventurist’ left wing groups (quoted in the Financial Times, 6 May 1974). It went on to insist that it should be part of the provisional government being formed by Spinola. The Times noted that

‘the mildly worded Communist statement barely mentioned the colonial wars and it openly condemned certain popular takeovers, criticising impatient left wingers.’

The Communist Party has not restricted itself to words alone. The Guardian has reported that

‘their leaders worked over the weekend to prevent a crippling strike at the national steef works across the River Targus from the capital... In helping to prevent a crippling confrontation at the plant, the Communists have, for the time being at least, thrown their weight behind the junta.’

To the left of the Communist Party the only significant organisations are groups of Maoists. These developed largely under French influence, and their impact is mainly confined to the student movement, which has been engaged in permanent confrontations over the last few years. Although in principle the Maoists should have an opportunity to extend their influence in the present period, their ultra-left and sectarian conduct makes it unlikely that they will do so.

As for the Socialist Party, it has virtually no base at all. It consists of a group of lawyers, doctors, etc, gathered around Soares. Soares himself is a moderate Social Democrat, distinguished by personal courage and honesty; he is uncompromised by fascism and has been jailed 12 times. His role will be to act as mediator between Spinola and the Communist Party.

THE BRITISH press, from The Times through to the Morning Star, have greeted the changes in Portugal with enthusiasm. They have stressed the joy in the streets of Lisbon, the feeling of national freedom and unity, the Morning Star proclaiming in its headlines. ‘A people united will never be beaten again’ (2 May 1974).

For revolutionaries, however, it is important not to be carried away by the mood of euphoria. The dismantling of the secret police, the emptying of the jails, the freedom for workers to organise, are all positive achievements of enormous importance. But the history of the working class movement internationally over the last century and a quarter shows that unless immediate steps are taken to intensify class struggle, such achievements can be reduced to nothing in a matter of months.

Reading accounts of events in Lisbon in the days after the coup, one is vividly reminded of Marx’s account of the revolution of February 1848 in Paris, when one section of the bourgeoisie was overthrown by another aided by the middle classes and the workers.

‘The provisional government which emerged from the February barricades necessarily mirrored in its composition the different parties which shared in the victory. It could not be anything but a composite between the different classes ... this was the February revolution itself, the common uprising with its illusions, its poetry, its visionary content and phrases ...

‘In the minds of the proletariat, who confused the finance aristocracy with the bourgeoisie in general ... the rule of the bourgeoisie was abolished with the introduction of the republic. At that time all the royalists were transformed into republicans and all the millionaires of Paris into workers. The phrase which corresponded to this imaginary abolition of class relations was fraternity, universal fraternisation and brotherhood. This pleasant abstraction from class antagonism, this sentimental reconciliation of contradictory class interests, this visionary elevation above the class struggle, this fraternity was the real catchword of the February revolution... The Paris proletariat revelled in this magnanimous intoxication of fraternity.’

But the euphoria of February 1848 was shattered four months later when the fundamental class divisions in modern society showed themselves to be more important than temporary divisions of interest within the ruling class. The bourgeois republicans consolidated their rule by turning the guns of their armed forces on the working class:

‘Fraternity, the fraternity of the antagonistic classes, of which one exploits the other, this fraternity, proclaimed in February, written in capital letters on the brow of Paris, on every person, on every barracks-its true, unadulterated, its prosaic expression is civil war, civil war in its most frightful form, the war of labour and capital. This fraternity flamed in front of all the windows of Paris on evening of 25 June (1848) when the Paris of the bourgeoisie was illuminated, while the Paris of the proletariat burnt, bled, moaned unto death. Fraternity endured just as long as the interests of the bourgeoisie were in fraternity with the interests of the proletariat.’

The lesson of 1848 has been repeated dozens of times since. Whenever one section of the ruling class turns against an established authoritarian government for its own reasons there are always powerful forces within the working class movement who try to hide the fundamental reality of class antagonism beneath a load of verbiage. Talk of ‘national unity’, ‘popular unity’ or ‘anti-fascist unity’ is used to justify leaders of the workers’ movement working hand in glove with the exploiting class. This leaves the ruling class free to disrupt the ‘unity’ when conditions are most suited to its own victory.

That is, of course, exactly what happened in Chile. For three years the leaders of the Communist and Socialist Parties preached ‘the unity of the army and the people’. At the end of that time, the generals felt secure enough to turn their guns on the people. Now in Portugal, the same reformist politics is leading the Communist Party to call for a ‘government of national unity’ containing both Spinola and themselves.

But the ‘unity’ which has emerged since the coup can only be a very short-lived unity. Clashes will inevitably develop between the interests of big business, which backed the coup in order to rationalise its exploitation of Portuguese workers and the African colonies, and the interests of the workers and colonial people who suffer from such exploitation.

When such clashes take place, what will matter will not be fine phrases about ‘national unity’, but the organisation, morale and physical force at the disposal of the rival classes.

Neither the Portuguese bourgeoisie nor the top army officers involved in the coup are politically naive. They will be preparing now for such an eventuality. They know that their political position has been weakened somewhat by the by-products of the coup – the break-up of sections of the police, the loosening of army discipline as part of the armed forces has fraternised with the workers and students.

They will work, behind the scenes, in the coming weeks to build up alternative police structures and to re-establish their control over the troops. They know they need time to achieve this, and will use alliances with Socialist, and Communist leaders to gain such time – providing such leaders promise to leave the state machine itself alone.

They have already indicated how this is likely to work, with talk of a provisional government headed by Spinola who would ‘appoint the civil provisional government, to be made up of persons representative of political parties and currents and also independent individuals who identify themselves with the aims of this [i.e. the military’s] programme’.

The Portuguese ruling class will hope that once it has reconsolidated its hold over the state machine, that it will then be able to dictate to the left wing parties terms for continued involvement in the government – basically that they use their influence to hold back workers’ living conditions. If the workers’ parties were unable to deliver the goods, the senior officers would then be able to threaten a return to direct repression.

The Portuguese left can prevent any such development. But only by following a policy quite different to that of the Communist and Socialist parties. The rank and file of the armed forces are clearly much influenced by the widespread popular distaste for the old order at present. The spontaneous reaction of workers to the coup has been to push for a purging of the state machine and for development of their own independent organisations.

The way to prevent reconsolidation of the repressive machine is to carry forward such spontaneous developments, to organise the rank and file soldiers against their officers, to step up the struggle over wages and conditions. In this way the disruption of the state machine can be spread, rather than be contained, and the involvement of the masses in the popular movement can grow even deeper.

But the precondition for any such development is rejection of the notion of ‘anti-fascist national unity’. A ‘government of national unity’ will of necessity operate within the bounds of the capitalist system and will therefore have to reject the demands of workers for real improvement in their living conditions and the demands of rank and file soldiers for an end to the power of the officers. It will hesitate about abandoning Portuguese rule in Africa. The danger is that some sections of workers will become disenchanted with political activity as they see that the ‘anti-fascist’ regime offers them little more in terms of living conditions than did the fascist regime, and that the more independently-minded of the rank and file soldiers will be cowed into submissiveness by the continuing power of the officers.

The only guarantee against a return to repression, perhaps on the Chilean scale, is the development of a revolutionary organisation that openly opposes the military and any provisional government, and which campaigns for the destruction of the present state machine and its replacement by working class power.

Last updated: 26.2.2008