ISJ 2 Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From International Socialism 2:44, Autumn 1989.

Transcribed by Christian Høgsbjerg.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

Thatcher’s attacks on the welfare state are deeply unpopular. Education has become an ideological and political battleground as teacher shortages threaten children with being sent home. Health workers’ action forced the NHS to the top of the political agenda in 1988 and the government is facing mounting criticism of its plans for reform. The Housing Act politicised housing for the first time in over a decade and resulted in tenants’ meetings on a scale not seen since the early 1970s – yet holding down welfare spending is still a major problem for the Tories. They are committed to keeping expenditure under control and, in some sectors, to major restructuring. These efforts have provoked controversy within their own ranks and bitterness outside.

Cuts in public expenditure have been on the Tories’ agenda since 1979, but in their own terms much still remains to be done. After a ten year war of attrition they have still not achieved major reductions in spending. Overall real wages in the public sector continue to rise. [1] Many Tory cuts have only tinkered with the system, cutting what is easiest in order to meet spending targets. School and hospital buildings have fallen into disrepair because these are the easiest items to freeze rather than because cutting spending on them is a government priority. The right wing still demands a more radical approach.

Thatcher’s first attempts to control public expenditure took place against a background of unfavourable circumstances. Recession, rising levels of unemployment and the increased number of old people meant that the Tories backed away from their goal of overall cuts. Instead they settled for reducing government expenditure as a proportion of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Recent inflationary pressure has produced a renewed desire to reduce the proportion of public spending, despite the boom of the last few years.

It was after the defeat of the miners in 1985, when the boom gave them the increased room for manoeuvre, that the Tories moved onto the offensive. The 1986 Social Security Act, passed in Thatcher’s second term, represented a major restructuring. This has been followed by major initiatives in education, housing and health. It would be wrong, however, to overstate the coherence of die Tories’ strategy. There are deep divisions in Tory ranks. This is clearest in the debates about the NHS. Radical proposals to create a two tier system, with better provision for the privately insured and a second rate NHS to mop up the rest, have been sidestepped by the government. The government’s embarrassments over the NHS disputes in 1988 stemmed from the Tories’ lack of a coherent strategy. The White Paper outlining their proposals for the NHS has increased dissent, both from health professionals and die broader public and those on me right who would like to see a more radical approach.

There is a tendency among left reformists to overemphasise the successes of Thatcherism. In particular they have focused on the ideological offensive and identified a new Thatcherite consensus over welfare. They argue that Thatcher has succeeded in rolling back the welfare state and creating a reactionary popular consensus in favour of privatisation, individualism and me virtues of the market. The evidence for these views was always slim, based on an unwillingness to acknowledge the possibility of working class resistance. The paucity of their analysis has become even starker in me light of recent struggles.

This article will look at the Tories’ offensive against the welfare state and attempt to assess how successful it has been. This is not to deny the terrible price mat has been exacted from some of me most vulnerable members of the working class as a result of the cuts. It is important, however, to understand me problems Thatcher faces. She has certainly had successes, although on nothing like the scale some left reformists believe. Nevertheless, there remain major contradictions and pressures. Workers’ resistance has prevented a repeat of the catastrophic defeats of the 1930s when relief for the unemployed was reduced by 10 percent and teachers’ wages were cut. Workers’ organisations in me public sector still survive. In what follows this article looks at four key areas: education, housing, social security and health. It starts with some general points about the welfare state and with criticism of the left reformist view of the effectiveness of Thatcher’s ideological attack.

Welfare provision is contradictory. On the one hand it benefits workers but on the other it also reflects capital’s interest in the reproduction of labour power. As Marx pointed out:

From the standpoint of society, then, the working class, even when it stands outside the direct labour process, is just as much an appendage of capital as the lifeless instruments of labour are. Even its individual consumption is, within certain limits, a mere aspect of the process of capital’s reproduction. [2]

The state represents capital’s interest in maintaining the conditions for the reproduction of labour power, but this imposes a cost on capital There is a constant tension between the desire for healthy, well trained workers and the costs of such provision. This tension is sharpened by international competition. There is also opposition to measures which could increase working class confidence or capacity to fight. Anything that might undermine workers’ ability or willingness to sell their labour power is likely to be resisted by me ruling class. Workers, on the other hand, have an interest in fighting to improve their housing, health, education and protection from destitution. There is therefore an inbuilt potential for conflict over welfare provision. The outcome depends on the balance of class forces.

The shape and type of welfare provision cannot be determined in advance or read off from supposed, predetermined ‘needs’ of capital. The welfare state is neither a plot by capital to control and discipline the workforce, nor is it a system for meeting people’s real needs. We need to understand the welfare state as an outcome of particular historical developments, which at the same time reflects the broader forces at work. [3] Three related factors have shaped the welfare state: the effects of war and especially the imperatives of total war, the increasing long term trend towards state intervention in the economy and the impetus for reform arising out of working class demands. The first two represent thee responses of the state to international economic and military competition, the latter militancy and political consciousness among workers.

The relationship between these factors can be seen historically in the development of free school meals for the poor in 1906 and the schools medical service of 1907. [4] These arose largely from ruling class concerns about the quality of labour power, brought home to them by the low calibre of recruits for the Boer War. An Interdepartmental Committee Report on Physical Deterioration in 1904 was influential in highlighting the problem. The Liberals’ willingness to act was also shaped by the election of 53 Labour MPs in 1906 and increases in both TUC and Labour Representation Committee membership. The success of the Liberals and Labour in the elections was, in part, due to anti-Conservative feeling following the Taff Vale judgement. Reform is not automatic however. Members of the ruling class did not willingly accept welfare provision for workers, especially when it came to paying. Lloyd George’s reforming 1909 budget proposing supertax and capital gains tax to fund this provision provoked a constitutional crisis when the House of Lords rejected it. The 1911 Parliament Act limiting the powers of the Lords followed Lloyd George’s vigorous defence of his so called People’s Budget:

The question will be asked, ‘Should 500 men, ordinary men chosen accidentally from among the unemployed, [the Lords – SC] override the judgement – the deliberate judgement – of millions of people who are engaged in the industry which makes the wealth of the country?’ [5]

With the Lords’ wings clipped the 1911 National Insurance Act had an easier passage through Parliament against the background of a wave of strikes in 1911–12.

The First World War had a major impact on social policy and acted to accelerate the increased role of the state. Public expenditure increased sixfold during the war and the National Debt rose from £650 million to £7,500 million. The Manchester Guardian believed this level of expenditure constituted ‘War Socialism’. The poor state of workers’ health was highlighted even more dramatically than in the Boer War. Only one in three conscripts were fit to join the forces. The Ministry of Health was first proposed as a war measure. War creates the conditions for massive social reordering. Lloyd George saw this clearly:

The present war … presents an opportunity for reconstruction of industrial and economic conditions of this country such as has never been presented in the life of, probably, the world. The whole state of society is more or less molten and you can stamp upon that molten mass almost anything as long as you do it with firmness and determination ... [6]

In war conditions governments feel the need to issue a social programme in order to mobilise the population. This, in turn, raises workers’ expectations.

In the immediate post-war period there was a massive wave of strikes, six million strike days in 1918, nearly 35 million in 1919. This provided an essential stimulus to reform. It produced a recognition that social reform was necessary as a counter to revolution. A cabinet memo to Lloyd George advised:

Bolshevik propaganda in this country is only dangerous in so far as it can lodge itself in the soil of genuine grievances ... A definite reiteration by yourself of the government’s determination to push forward with an advanced social programme is the best antidote. [7]

Lloyd George understood the need to redeem his promise of ‘homes fit for heroes’. In the debate preceding The Housing and Town Planning Act 1919, which invested local authorities with a statutory duty to remedy housing shortages and provided Treasury money for this purpose, he commented to his cabinet, ‘Even if it costs a hundred million pounds, what was that compared to the stability of the state?’ [8]

Many of the advances of the immediate post-war period were sharply curtailed by the recession of 1922. Developments in social welfare are constrained by the state of the economy. The economic crisis resulted in a 10 percent cut in relief to the unemployed in 1931 as MacDonald vainly struggled to maintain Britain on the gold standard. The memory of this defeat among workers was significant in the development of post-Second World War social policy.

All the factors affecting welfare present in the First World War emerged more dramatically in the Second World War. The mass mobilisation of the population (described by Angus Calder as the ‘People’s War’) provided a massive impetus to reform, while state expenditure and control of the economy advanced even further. [9] The Beveridge Report of 1942 is seen as founding the modern welfare state. The post-war development of welfare was based on wartime mass radicalisation and the widespread feeling that society must be different. There were queues outside the shops to buy copies of the Beveridge Report and over 635,000 copies were sold. A Gallup Poll two weeks afterwards found that 19 out of 20 people had heard of the report and nine out of ten were in favour of its proposals. Beveridge was not the only significant war time report. In 1944 the White Paper Employment Policy committed die government to high and stable levels of employment and marked the acceptance of Keynesian management of the post-war economy. As in the First World War these concessions marked a realisation by the ruling class that, as Quintin Hogg (later Lord Hailsham) put it in 1943,

If you don’t give people reform they are going to give you revolution. Let anyone consider the possibility of a series of strikes, following the present hostilities, and the effect it would have on our recovery. [10]

Post-war reform was meant to provide the basis on which British capitalism was to be made more productive.

The war itself had necessitated massive reorganisation anyway. The old system of voluntary hospitals and municipal hospitals had to be radically restructured to meet war time needs. The government made medical supplies available on a massive scale and created a national blood transfusion service. Under the Emergency Scheme patients received free treatment and were directed to those hospitals that could best meet their needs. The system was geared to the needs of the war effort and so the elderly and others suffered badly, nevertheless it did provide a ‘national’ hospital service.

The shape of the welfare state therefore reflected contradictory pressures. On the one hand it represented real reform under the pressure of workers’ demands and the landslide Labour victory of 1945. Equally, it developed under the pressures of the needs of total war. Vested interest groups battled to ensure that its post-war shape did not damage them. From the beginning the National Health Service made concessions to the vociferous BMA lobby. [11] Nor did the Labour government press the radical reforms its mandate warranted. A BMA member described their meeting with the Labour minister:

We assembled at that first meeting expecting that our beautiful profession was to be hung, drawn and quartered. Instead we were reprieved… on one point after another – control by local authorities, the free choice of patient and doctor, clinical freedom – the Minister had accepted what we were demanding before we had the opportunity of asking for it. [12]

Similarly Beveridge was careful to ensure that his scheme would not interfere with market forces. The flat rate principle in the National Insurance scheme was such that the low level of provision would not affect saving:

Provision by compulsory insurance of a flat rate of benefit up to subsistance level leaves untouched the freedom and responsibity of the individual citizen in making supplementary provision for himself above that level. This accords both with the condition of Britain, where voluntary insurance particularly against sickness is highly developed, and with British sentiments. [13]

These ‘British sentiments’ have ensured that the profits of the insurance companies have not been interfered with whatever the political complexion of the government. It is also true that the benefit available to the unemployed has never interfered with their willingness to sell their labour power.

National Insurance operated on the assumption that the reproduction of labour power is primarily a private matter for the family and that women are dependent on men. The welfare state presumes ‘women are carers’. This is contradictory, however, because increased welfare spending has massively increased employment for women, enabling them to move outside the home. Their role as workers in the welfare state has put women in the forefront of struggles over welfare spending.

Which particular elements of the welfare state are deemed necessary to capital is also the subject of controversy within the ruling class. There is also a continued concern about costs and who should bear them. As Jim Kincaid pointed out, successive governments used National Insurance contributions to ensure that only a limited part of unemployment benefit is funded through general taxation and that the major redistributive effects are primarily between members of the working class. [14] The concern with cost is part of a general desire to limit the costs of the reproduction of labour power. The main concern is holding down wages, but this extends to limiting welfare spending. Marx points out that additional consumption by workers is seen as unproductive:

Hence both the capitalist and his ideologist, the political economist, consider only that part of the worker’s individual consumption to be productive which is required for the perpetuation of the working class, and which therefore must take place in order that the capitalist may have labour power to consume. What the worker consumes over and above the minimum for his own pleasure is seen as unproductive consumption. If the accumulation of capital were to cause a rise in wages and an increase in the worker’s consumption unaccompanied by an increase in the consumption of labour-power by capital, the additional capital would be consumed unproductively. [15]

Edwina Currie (then at the DHSS) could have had this in mind in her infamous exhortation to workers to give up their second holidays and take out private health insurance instead!

Attempts to cut spending are often described as attacks on the ‘social wage’. The concept of social wage is useful in so far as it correctly emphasises that cuts are a collective attack on workers’ living standards. The term ‘wage’ is misleading however. Welfare spending is not directly linked to the sale of labour power, although it forms part of the reproduction of labour power. The link for the capitalist is therefore an indirect one. Capital in general does benefit, although individual capitalists may bitterly oppose specific measures. Marx describes the fierce struggle of capitalists against me Ten Hours Act and other factory legislation which in the longer term benefited capital by protecting the conditions for the reproduction of labour power. For workers too the link with welfare provision is indirect. This means that the struggle for improved provision reflects a political consciousness as well as levels of militancy.

Much emphasis has been placed by left reformists on the influence of the New Right on cuts in welfare spending. [16] Stuart Hall and others around Marxism Today have stressed the significance of a ‘new hegemony’. [17] But a glance at Tory propaganda reveals a much more cautious presentation of their ideological themes combined with a pragmatic desire to be seen as supporters of popular parts of welfare spending, in particular the NHS.

The 1979 Tory manifesto was consciously based on support for the individual and the family and against state intervention. The section of the manifesto that deals with what we would call the welfare state is entitled ‘Helping the Family’ – the term ‘welfare state’ is not used at all. The section begins with the sale of council housing and moves on to the other ideologically key area, education, with a stress on ‘parents’ rights and responsibilities’. The tone is hardly strident, however. On ‘health and welfare’ the message is deceptively reassuring:

The welfare of the old, the sick, the handicapped and the deprived had also suffered under Labour. The lack of money to improve our social services and assist those in need can only be overcome by restoring the nation’s prosperity. But some improvements can be made now by spending what we have more sensibly.

As with previous Labour governments the rhetoric of ‘community’ care is present, but there is no open battle cry against the public provision of caring services. The 1983 Tory Campaign Guide similarly stresses the achievements of the government in terms of social and health spending. [18] The 1987 manifesto is couched in most reassuring terms in relation to health, a continuation of Thatcher’s notorious claim that the NHS was ‘safe in her hands’.

Thatcher has moved British politics further to the right, but the roots of this shift go back to the previous Labour government’s response to economic crisis in the mid-1970s. And in practice her policies have frequently been marked by pragmatism and inconsistency. The government retreated from plans for parents to ‘buy’ private or public sector education using ‘educational vouchers’ in the face of growing evidence of impracticability. Student loans were initially rejected on the same grounds.

An argument put by Stuart Hall in explaining attacks on welfare spending is that anti-collectivism and anti-statism formed ‘a new kind of taken-for-grantedness: a reactionary common sense’ [19] which was mobilised on the basis of popular discontent with the welfare state. This claim is based on no real evidence.

The evidence for the unpopularity of welfare spending is not born out by opinion poll results. [20] The 1980 MORI poll found that, while 44 percent favoured cuts in social security benefits, 36 percent favoured an increase in education and 57 percent favoured an increase in NHS spending. Support for increased state spending in these areas has increased during the Thatcher years. In 1983 those favouring increases in education had risen to 55 percent, and 59 percent for the NHS. A poll just prior to the 1983 election found that 32 percent favoured an increase in taxes to allow for increased spending compared to 9 percent who favoured reduction. The 1986 British Social Attitudes survey showed that even among Conservative voters only 8 percent wanted tax cuts if that meant less spending on health, education and social security. Only 6 percent of Tory voters favoured cuts in welfare! Evidence from a Marplan poll for Channel 4 in April 1988 revealed considerable dissatisfaction with the government’s record. [21]

More sophisticated attempts to analyse public attitudes by academics also reveal strong support for state spending, despite the perception that private provision offers better standards in both health care and education. This is hardly surprising since the private health care and education available to the rich is an aspect of their privilege. One academic concludes:

If private is seen as superior to state, the main reason for this is the view that the private services have more resources at their disposal. So people’s perception that the private sector is currently ahead of the state sector tends to lead them to want more resources for the state sector. It does not mean they want the private sector to replace the state sector, nor that they support private management or efficiency savings in the state sector. [22]

Dissatisfaction with state provision leads to demands for improved state services. The Economist has pointed out that one of the ironies of Thatcher’s rhetoric of more parental control in education and more choice in the NHS is that it increases demand for improving services and spending rather than dampens it down. [23] Far from pointing to a new Thatcherite consensus opposed to welfare spending all the evidence shows the government has increasing problems dealing with demands for better provision.

Britain’s long term competitive weakness in the world economy has been further exposed by the period of world economic crises. [24] Cuts in public expenditure are part of the general offensive designed to restore British capital to prosperity. Pete Green has shown that monetarism was neither unique to Thatcher nor realised in practice. However, monetarism provided a rhetoric which presented increased unemployment and falling output as merely unfortunate side effects of necessary monetary stringency. Thatcher has repeatedly stressed that expenditure depends on prosperity. The years 1979–82 were marked by a deep slump. The Tories’ early priority was to cut public expenditure.

Tory strategy has to be understood against a long term trend for public expenditure to rise in all advanced capitalist economies. This general rise is, however, punctuated by crises in the economy. This can be illustrated by looking at the figures for public spending in the post-war period.

|

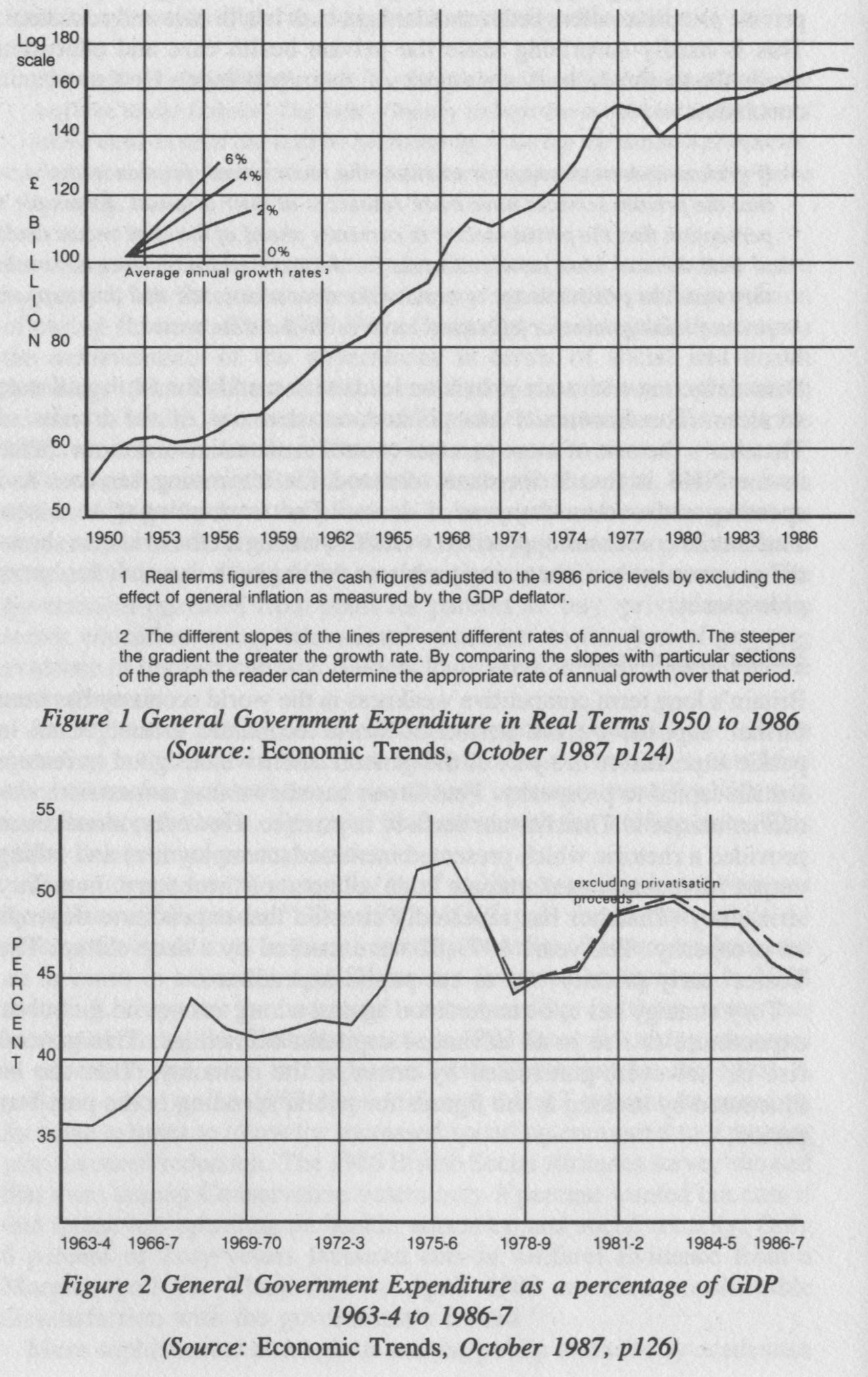

Figure 1 shows an accelerated rate of increase in public expenditure in the 1960s to about 4.5 percent a year. Spending peaked in 1968, followed by cuts in 1969, and then peaked again in 1975. A large balance of payments deficit in 1976 sent the Labour government scuttling to the International Monetary Fund. As a result of cuts public expenditure fell in real terms in 1976–7 and again in 1977–8. The other way of looking at public expenditure is as a percentage of GDP.

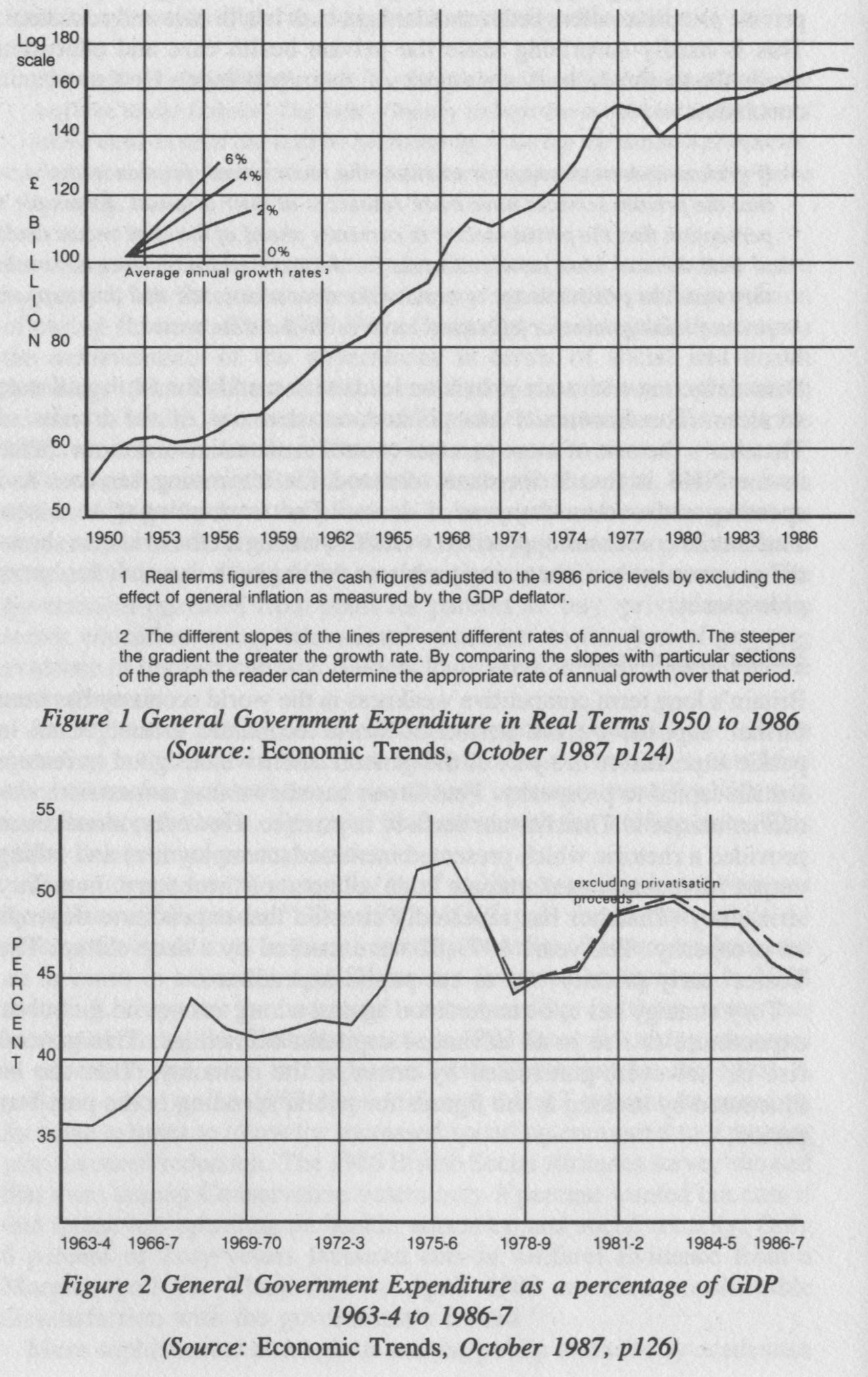

As a percentage of Gross Domestic Product public expenditure rose to a peak of 48.5 percent in 1975–6. After falling, it then rose again to 46.8 percent in 1982–3, after which it declined to 44 percent in 1986–7.

The number of workers employed in the public sector fell from 30 percent of the total workforce in 1981 to 26 percent in 1986. This is accounted for by privatisation and the transfer of workers from public to private corporations. The overall numbers employed under the category of general government remained constant at 5.3 million from 1976. At the same time manufacturing employment fell by 2 million after 1979 and service sector employment contracted in 1979–83, only resuming growth after 1984. Between 1987 and 1988 employment in public corporations fell by 7.2 percent, mainly due to privatisation, but general government employment increased by 0.5 percent.

How then are we to judge the Tories’ success in cutting public expenditure? The first and very obvious point is that the attacks on welfare spending did not begin with Thatcher. They are a product of both the broader crises affecting British capitalism and the outcome of the class struggle. It is not the case, however, that when the ruling class attack wages they automatically focus on welfare spending as well. Despite the Tory Heath government’s direct attacks on workers’ living standards, public expenditure increased from 1970 to 1974. His government came to grief in the face of the miners’ militancy in 1974. Labour was elected in 1974 on the slogan of ‘Get Britain back to work’ and immediately raised pensions, froze council house rents and repealed the Industrial Relations Act. However 1975 marked a turning point. The economic crisis forced the Labour government onto the offensive and Tony Crosland proclaimed, ‘The party’s over.’ [25] The Social Contract directly attacked workers’ living standards through wage restraint and Dennis Healey announced a £1 billion cut in the Public Sector Borrowing Requirement in 1975–6, followed by a further £3 billion cut in 1976–7. According to the Treasury model, these cuts led to unemployment being 600,000 higher than it otherwise would have been.

The effects of cuts on the welfare state were dramatic. The review of supplementary benefits in 1978 left some claimants worse off. Pension reform made the state scheme residual and encouraged massive contracting out, rescuing the insurance companies and pension funds from the ravages of inflation. Child Benefit was the only victory for the TUC and the poverty lobby but was set at a level less than its equivalents (Child Tax Allowance and Family Allowance) had been ten years earlier. Having initially frozen rents Labour allowed them to rise rapidly. Council house building declined in 1979 to its lowest level since 1945, reducing it to residual provision for the needy. Labour also accepted owner occupation as the norm. The reorganisation of the NHS produced a more ‘businesslike’ management structure. The redistribution of funds through RAWP (Resource Allocation Working Party) was initially designed to equalise NHS expenditure throughout the country, but it became a mechanism for distributing cuts and closing hospitals in ‘over-provided’ areas! Many of the hospitals closed or threatened were in the most deprived areas of London. [26]

Labour efforts also paved the way for Thatcherism’s ideological attack on public spending. It was Callaghan in 1976 who publicly abandoned the commitment to full employment. The strategy of direct wage control was only derailed by the 1978–9 ‘Winter of Discontent’. British capital was ready to risk more radical solutions to the crisis by abandoning elements of corporatism in favour of a shake out of capital and a more openly confrontational stance towards the trade unions. Thatcher promised more of the same.

How has Thatcher fared? In 1979, far from cutting total public expenditure, spending increased as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). It had been successfully cut for the previous three years. The problems that Thatcher faced were twofold. One was the increased level of unemployment which automatically increased social security payments. The other was the ideological commitment to increased spending on defence and law and order, and the pre-election promise to protect health services. The failure to cut total public expenditure led the government to accept more limited objectives. They shifted from aiming for absolute cuts in public expenditure to reducing the percentage of GDP spent by government. The 1984 Treasury Green Paper The Next Ten Years: Public Expenditure and Taxation into the 1990s gave two projections, one for no real increase in public expenditure, the second for a 1 percent increase, both based on projections for growth that would reduce public expenditure as a percentage of GDP. The government’s backdown infuriated right wing ideologues from the Institute of Economic Affairs who have criticised the government’s ‘inability’ to make cuts. [27]

The aim of cutting public expenditure, even as a percentage of GDP, nonetheless necessitated attacking both services and public sector workers. Cuts went hand in hand with rising absolute levels of public expenditure. The aim of controlling expenditure was achieved slowly. Until 1984–5 public expenditure increased, but then fell as a proportion of GDP in 1985–6, although it was still a higher percentage than when Thatcher took office. If privatisation proceeds are taken into account the figures are lower but the overall pattern remains the same. Privatisation has helped to keep down expenditure by contributing about £5 billion a year. Privatisation does not contribute to cuts in net expenditure on general government consumption since it has a one-off effect and potentially profitable areas are lost. In real terms general government expenditure increased to 1985 and then flattened out.

The recent growth in the economy has benefited the government’s attempt to control expenditure as a proportion of GDP. Gross Domestic Product has been growing at a rate of 4.3 percent since 1986 and at 4.4 percent in 1988. This has enabled the government to cut the proportion of public spending to its lowest levels since 1970 while still finding the funds for real increases in expenditure. [28] Receipts rose by 9.5 percent between 1987 and 1988, producing a current account surplus of £7,100 million, a negative public sector borrowing requirement. [29] This allowed planning totals for to rise in real terms by after four years of remaining flat, with predictions of a 7.6 percent rise between 1989–90 and 1991–2 (in time for die next election). [30] But even the recent boom does not solve the problem of welfare spending. The fears of rising inflation are now producing pressures to revise these figures downwards. At the same time the results of past stringency are giving rise to calls for greater spending on roads, schools and the NHS. Further bitter conflict over spending totals looks inevitable.

The Tories have ensured that as far as possible the working class pays for its own welfare benefits. They have shifted the burden towards indirect taxation. The 1988 budget cut me top rates of income tax to 40 percent, giving £2 billion to the top 5 percent of wage earners. Two billion pounds was the amount of cash that it had been argued was necessary to alleviate the crisis of provision in the NHS. This money has now gone towards further widening the gap between the incomes of me top 10 percent and the poorest 10 percent. The top 10 percent had 6.5 times more income than the bottom 10 percent in 1979, and in 1987 they had 8 times more. In 1988 with the additional benefits to the rich of the budget as well as soaring salaries the top 10 percent look likely to reach the position of having nine times as much income as the bottom 10 percent. The poll tax will further this process and is producing an increased bitterness against the rich as they visibly benefit at the expense of the working class. There is nothing new in the strategy of making workers pay an increased proportion of welfare costs, Thatcher has made dramatic advances in rendering me tax system even more inequitable.

The following sections will deal with education, social security, housing and health. Each section will assess the Tories’ aims and evaluate Thatcher’s success in making real cuts in expenditure. The extent to which she has succeeded in restructuring has depended in part on resistance in that sector and on the general level of class confidence. But there have also been divisions in the Tory ranks about the best ways to restructure welfare to meet the needs of competitive capital. Far from being a coherent monolith, Thatcherism in practice has followed a twisted path. Thatcher has undoubtedly inflicted damage and misery, especially on the increasing numbers of the poor. But in terms of cuts and on the ideological front the war is one of attrition, of contradictions and crises, rather than outright class victories.

The education system delivers differentially skilled labour power to capital, but how this is achieved varies. International comparisons reveal Britain’s poor record in educating those over 16 years of age. But if and how this will be redressed depends on political forces. The government has cut back on university places while expanding cheaper polytechnic places. It has offered so called ‘training’ on YTS schemes rather than provide real educational opportunities for the majority of over 16 year olds. There are disputes within the ruling class about the significance of education for British capital’s effectiveness. Employers express their concerns but have been reluctant to fund new developments.

More general political concerns also shape educational policy. The most obvious is the desire to control public expenditure. This explains the priority the government places on attacking teachers’ wages and conditions and their desire to drive down unit costs per student. But ideological considerations also play a role. The government defends more expensive grammar school sixth forms even when Labour councils have proposed reorganisation designed to cut costs. Educational policy for the over 16s has been closely tied to massaging the unemployment figures. It has been less concerned with any coherent notion of education or training than with disciplining young people into work routines. Ideological disputes have particular significance in education because ‘ideas’ and ‘values’ are central to the transmission of knowledge. One of Thatcher’s achievements has been to override the previous social democratic consensus that education should be about equality of opportunity and should therefore reflect egalitarian values. It is important, however, not to overstate the changes in ideology and policies. The previous egalitarianism never resulted in more than a minority succeeding and the Tories have not been able to push forward on some of the more radical proposals argued for by the new right.

Nevertheless education has become a more clearly politicised area with sharpened debate on the purposes, content and organisation of provision. The government is attempting to determine the content of the curriculum. This is part of the continued attack on the already limited autonomy and organisation of teachers. National control is also seen as a mechanism for pulling education into line with the needs of employers. There is a contradiction at the heart of this. The Tory hankering after ‘traditional values’ may in practice be pulling in the opposite direction to the competitive interests of British capital. [31] So the traditionalists’ desire to see children drilled in their tables provides an absurd contrast with the widespread use of calculators and computers in industry. These contradictions have made education one of the more controversial areas of government policy.

Education has had a high political profile since the 1979 manifesto set out the Tories’ proposals for increasing parental rights on the basis of their ‘Parents’ Charter’. As soon as they were elected the Tories saved the remaining grammar schools by repealing the 1976 Education Act. They then passed the 1980 Education Act, which gave the Parents’ Charter legal force. This act gave middle class parents increased choice of schools for their children. Local authorities had to provide parents with more information on admission criteria, examination results and other policies. In 1981 the Tories issued a document on a core curriculum for five to 16 year olds that was eventually to lead to Kenneth Baker’s great Education Reform Bill.

The government proceeded with a degree of pragmatism and political caution, however. Much to the fury of the New Right it backed off from education vouchers in 1983. [32] In 1976 while in opposition the Tories had proposed a motion in parliament for experiments with vouchers. When he became education secretary Keith Joseph had responded favourably to the right wing pressure group FEVER (The Friends of the Educational Voucher Experiment in Representative Regions). Despite Joseph’s clear political support the government retreated, in the face of mounting evidence of impracticality, from the political confrontation that introduction would have produced. In a television interview in 1983 Joseph was forced to admit that, ‘There would have been a great deal of controversy in our own party as well as across party lines.’

In Thatcher’s second term, from 1983, the government looked less sure of its direction. Student grants had been steadily eroded by inflation. The Central Policy Review Staff proposals to introduce student loans and to charge students full cost fees were both rejected. Keith Joseph scored an own goal in 1984 when he proposed that those students who were ineligible for a grant should pay their own tuition fees of about £520. These proposals would mainly have affected Conservative voters. Their reaction forced Joseph to execute a prompt U-turn. The recognition that Joseph’s strident ideological tone was creating problems led to his replacement by the apparently more moderate Kenneth Baker. But education continued as an irritant to a government angered by what it saw as irresponsible local authority control. Baker expressed this frustration:

Many people have no idea how decentralised the education system is. I get just as frustrated as parents when I read that this or that school is short of textbooks, or needs a coat of paint. I think it is important to realise I am not responsible for that … My privilege is largely restricted to picking up the bills which other people run up. [33]

All the themes of the Tories’ first two terms, parental choice, core curriculum, irritation over local authority control (both in terms of financial control but also ideological attacks on anti-racist and anti-sexist teaching) came together to produce a major restructuring, the 1988 Education Reform Act. Despite the failure to introduce vouchers the Education Reform Act has further strengthened ‘parental choice’. Under Baker’s scheme parents are to be given access to the school of their choice up to the school’s full capacity.

Baker offers middle class parents ‘choice’ of more popular schools in affluent areas, but he offers nothing for working class children. Worse, as the Dewsbury schools dispute showed, the logic of ‘choice’ could lead to ‘whites only’ schools, and in the process create all black sink schools. The government is abandoning the mass of working class children to a second rate education. Selective City Technology Colleges (CTC) will offer specialised education in some areas, although employers have been reluctant to fund these projects on the scale envisaged by Baker. The government has been forced to provide capital as well as running costs, with the result that in eight out of the ten CTC authorities ten times more is being invested in one CTC than the entire capital spending for all the other schools in the area. [34]

Behind Baker’s restructuring is a clear attempt to roll back some of the gains teachers have made in terms of the education of working class children. [35] The curriculum reforms are designed to squeeze out the limited advances in teaching methods and courses, such as integrated humanities. It was in these areas that some teachers had allowed discussion of the roots of racism, and the nature of class and gender divisions. The Tories want the common curriculum to reintroduce old fashioned grammar school virtues. But even here they have not had it all their own way. The Kingham report [36] into the teaching of English did not come down, as expected, in favour of formal grammar teaching. [37] The subsequent Report was chaired by the notorious right wing educationalist Brian Cox, but he also failed to specify grammar. As a result Baker stepped in to overrule his advisers. The right wing Centre for Policy Studies was not appeased and continues to demand stricter targets. [38] This seemingly byzantine argument over whether Standard English is a dialect (a grammar and vocabulary, not merely an accent) and whether seven year olds should know a noun from a pronoun is clear evidence that members of the ruling class are divided on the desirable educational norms for the next generation of workers. Thatcher was reportedly unhappy with the Kingham Report which favoured school administered English tests, while Baker found it ‘interesting’. Similar divisions can be seen on opting out. It appears that Baker expects this to apply to only a minority of schools (as appears to be the practice), whereas Thatcher favours a massive breakup of local authority provision.

These disputes are not over the basic aim of producing an education system that delivers a stratified workforce with the necessary skills, but about how this is to be achieved. At the same time as the emphasis is on basic skills, schools are being encouraged to make ‘compacts’ with local employers to give pupils work experience and improve motivation by the promise of a job. Teachers were even being exhorted to give up their holidays to work in local industry! The government is attempting to marry its twin concerns of increased relevance to industry and traditional values, based mainly around simplistic notions of self discipline. It looks likely that disputes will continue at the ideological level.

The main cost in education is teachers’ wages. This explains the determination with which the Tories fought the teachers in 1985–7. Wages account for 60 percent of expenditure. This means that the normal way of calculating real spending increases gives an overestimate of rises in education expenditure. [39] One statistician recalculated the figures between 1979–80 and 1984–5 using education specific prices. The result shows a 6 percent fall in real spending. [40] The Tories have reduced education spending as a percentage of GDP and cut capital spending in absolute terms. Cash limits have been in operation since 1976 but since 1982–83 they are the sole form in which expenditure is expressed. The real level of inflation is therefore critical in determining the level of services provided.

The other key constraint for the government in cutting expenditure is demand. Unlike other areas of welfare provision the schools sector has seen a fall in demand because of falling birth rates. School student numbers fell by 17 percent in the primary sector between 1976 and 1986, increased slightly in 1987 and are projected to increase to 1998. Secondary school numbers fell by 12 percent to 1987 and are projected to continue falling until 1991. [41] This means that despite the overall reduction in real expenditure there have been increased in expenditure per head. Average class sizes, which had been falling in primary schools, increased slightly between 1981 and 1987 whereas in secondary schools they continued to fall marginally. The story is not simply one of massive cuts in schools.

This contrasts starkly with teachers’ perceptions that the cuts have bitten deeply into their working conditions. One of the reasons for this is that capital spending is now substantially below its 1978–9 levels. Capital spending accounts for only 4 percent of total budget compared to 15 percent in the early 1970s. Because capital accounts for such a small percentage of total expenditure these cuts don’t show up in the overall figures, but the squalor of many schools is a daily reminder of inadequate state provision. Unevenness of falling rolls also means that, although class sizes on average have fallen, in some places class sizes have increased. Staff/student ratios also take no account of new demands made by the GCSE and the national curriculum.

The demoralisation that followed the imposition of new contracts and salary scales on the teachers and the productivity increases associated with new examinations and teaching account for teachers’ bitterness in many schools. Teachers’ action did force concessions from the government but the imposition of wage deals below inflation is eroding pay. This is in turn gives rise to new problems and contradictions as recruitment has been hit. The scale of the difficulties is reaching crisis proportions in some London boroughs where there are predictions of part time education for some children. [42] The shortage of specialist teachers will make the introduction of the national curriculum impossible in some areas and a longer term problem looms as a result of the failure to recruit students in shortage areas. But teacher organisation has not been destroyed and this represents a real curb on the government’s options.

The Tories have been more successful in attacking the school meals service and the conditions of the lowest paid ancillary workers in education. In 1980 the statutory duty to provide school meals was abolished except for children whose parents claimed the old Family Income Supplement or Supplementary Benefit. The numbers of children eating school meals fell as prices rose. Some Tory councils worsened the conditions and pay of their workers while others ditched parts of the service altogether, leaving the children of the poorer sections of the working class with packed lunches. Families in receipt of the new Family Credit which replaces Family Income Supplement will no longer be entitled to free school meals, thus eroding the welfare aspects of die education service even further. This is significant as in low income families the school meal provides a significant part of a child’s nutrition and a further increase in malnourishment among working class children is likely.

The government are now forcing through student loans, despite widespread opposition. The banks have shown extreme reluctance to act as debt collectors and have forced conditions which mean that public expenditure savings are unlikely. The ideological importance attached to student loans has overridden this scepticism. But loans fly in the face of other government plans to increase access to higher education, driven as they are by the realisation of Britain’s relative weakness internationally. Student numbers are being increased on the basis of reduced unit costs, and restructuring and attacks on pay and conditions have produced resistance among staff as well as students. The government has changed the way further and higher education is financed. They have removed most higher education from local authority control and instigated measures to ensure greater competition between institutions for central government funding. Increasingly colleges are being forced to fund their own developments through economic costing of courses.

The government’s strategy in education has been one of attempting to contain costs while restructuring education to fit the needs of the market. This is not new. The ‘Great Education Debate’ was initiated by Callaghan in 1976. The Manpower Services Commission was an invention of the Labour government. The Youth Opportunities Scheme in 1978 was the precursor of YTS. Reform in education remains controversial partly because it affects middle class parents. It is their children who gain more from the education budget. The Education Reform Act will produce a more unequal education system, yet there is no general support for cuts in education, nor did it prove possible to promote the idea of ‘privatising’ education through the voucher system. Loans remain deeply unpopular. Contradictions are piling up in a school system faced with acute teacher shortages as employers demand a more literate, numerate and skilled workforce. The disputes within the ruling class as to the relationship of education and training to economic needs, along with teacher bitterness, suggests that the skirmishes over the implementation of the Reform Act will be drawn out. Some of Keith Joseph’s simplistic fervour for remoulding education has been abandoned, but the 1988 act represents a major shift away from progressiveness and egalitarianism in education. Education budgets will continue to be shaved, perpetuating a second rate service for the majority, increasingly boosted by parental payments in middle class areas. As a result of Tory policies education is both more controversial and less likely to be able to satisfy either employers or students. At every level the potential for conflict remains high.

Housing costs form a significant part of the cost of the reproduction of labour power. There is no general political commitment to subsidising this element of workers’ consumption, although in practice subsidy takes place in a variety of forms. But, unlike health and education where private provision is widely regarded as only a supplement to state provision, mere is widespread support for private housing. Thatcher has developed privatisation as a key ideological theme. House ownership has also been linked to ideas about wealth, inheritance and citizenship. The ‘right to buy’ has a central place in the rhetoric of ‘choice’, independence from the state, and the family. Thatcher’s boast in 1982 (in relation to council house sales) was:

This is the largest transfer of assets from the state to the family in British history and it was done by a Conservative government.

Housing demonstrates the contradictions of the market. Left to market forces most workers cannot afford decent housing. Private ownership is dependent on a massive indirect subsidy, and both rises and falls in house prices create severe problems. Thatcher’s success in breaking up public housing is now creating the sorts of problems that in the past led to state intervention in direct provision.

The right to buy was the centrepiece of Tory policy in their first term. The 1980 Housing Act gave local authority tenants the right to buy their houses after three years tenancy, with subsidies of between 33 percent and 50 percent. By the end of 1982, 430,000 local authority, new town and housing association houses had been sold. The Housing Act also increased local authority tenants’ rights in such matters as the right to take in lodgers, sublet and improve. The private rented sector was also given encouragement with a new shorthold system of letting from one to five years which guaranteed the landlord repossession. The Tories created ‘assured tenancies’ whereby landlords could build for ‘freely negotiated’ rents, in other words outside the protection of the fair rents provisions of the Rent Act. They also ended the system of controlled tenancies under which rents were pegged to 1956 levels. Alongside these concessions to private landlords was a massive increase in home improvement grants from £197 million in 1981–2 to £911 million in 1983–4. In contrast council house rents increased by 119 percent between 1979 and 1983. Public building plummeted from the already miserably low 1979 levels.

The second term produced more of the same. The 1984 Housing and Building Control Act increased the discount available to council tenants buying their houses to a maximum of 60 percent and reduced the qualifying period to two years. The 1986 Housing and Planning Act further encouraged flat dwellers to buy by adding an extra 10 percent discount for sales of flats. As a result of these moves and the unavailability of council housing, house ownership rose from 57 percent in 1979 to 63 percent in 1987. A massive subsidy goes to home owners in the form of £4.75 billion in lost revenue as a result of mortgage tax relief. Despite some easing the Tories waited until their third term before attempting to fundamentally alter the balance between landlord and tenant.

The 1988 Housing Act, the centrepiece of Thatcher’s third term assault on council housing, aims to increase private renting and force local authorities to give up large chunks of their housing stock. The government is attempting to restructure the housing market and has radically undermined the rights of tenants. The Housing Act extends ‘assured’ tenancies to all new tenants. Rents will no longer be fixed as a ‘fair rent’ under the 1977 Rent Act. Instead they will be struck as a ‘free bargain’ between landlord and tenant, or fixed as a market rent by the Rent Assessment Committee. Security of tenure is reduced or in the case of assured shorthold tenancies removed completely.

Assured tenancies represent a major attack on tenants and are designed to increase the availability of privately rented accommodation. This is unlikely to occur. It was the failure of the private sector to provide affordable private accommodation that led to the expansion of public housing. Inadequate provision has been made in the Housing Benefit budget for new market rents, a miserly 3 percent rise. [43] New rules mean that a rent officer can decide that accommodation is ‘over large’ for the claimants’ needs – children under ten years must share a room regardless of the sex of the child, and all children of the same sex must share a room regardless of their age. [44]

The Housing Bill was launched on the basis of increased tenants’ choice. [45] The ‘pick a landlord’ scheme, however, rapidly became ‘change a landlord’ as it became clear that it was the landlord, not the tenant, who would do the choosing. After a new private landlord has decided to take over the property tenants are allowed to vote for the new landlord, or for continued local authority control. The other even more draconian provision is for the creation of Housing Action Trusts. Government appointed HATs can simply take over chronic estates to improve them. The government only allowed tenants to be consulted after a wave of protest meetings and rallies by tenants. Tenants are now allowed a vote. Originally HATs were proposed for 16 council estates, affecting 25,000 homes. The government was forced to retreat in the face of protests and only about a third of these are now planned. So far no official ballots have been organised. The Tories dare not risk damaging ballot defeats.

The final provisions of the act affect Housing Association finance. Current levels of grant, over 90 percent, from the government could fall to as low as 50 percent, leaving them to raise the rest of money on the open market. The need to service these loans will mean either higher market rents or building to a reduced standard, or both.

There were also measures designed to increase the private rented sector in the 1988 Budget. These gave 60 percent tax relief for business investments in housing. One moderate commentator at the time of the Housing Bill assessed the proposals:

… the government is, in my view, recklessly putting at risk the country’s ability to supply decent quality affordable rented homes for the poorest households. [46]

The government’s other major proposals, in the 1989 Housing and Local Government Bill [47], would prevent local authorities subsidising rents from the rates or poll tax. The clear intention is to make private landlords seem a more attractive proposition to tenants when they vote in ‘change a landlord’ ballots. Local authorities will be left with statutory rights to house the homeless with an increasingly diminished stock from which to meet the obligation. The bill changes the basis of control for housing finance from controls on spending to control on borrowing. This will allow the government to earmark money to be used in certain ways. It will be a way of forcing new developments into the hands of housing associations or other landlords, since the government has no intention of approving credits for local authority building. The cumulative effects of virtually no new building, council house sales and now the threat of measures in the Housing Act mean that the council house stock is severely depleted.

Cuts in housing expenditure have been dramatic. However, the restructuring of housing finances away from council housing is even more significant. Housing expenditure fell in real terms from when Thatcher took office. It fell even in cash terms from £4,052 million in 1984/5 to £3,682 million in 1987/8, a 9 percent cut in money. The largest cut was in central government subsidies to local authority housing, mainly in the form of a reduction in the subsidies on council rents. The reduction in expenditure is not as great as it might appear, since the number of council tenants eligible for rent rebates (now under the Housing Benefit Scheme) has also risen sharply, resulting in spending increases in the social security budget. [48] Therefore part of the expenditure was simply transferred to the social security budget. This did not protect tenants though, as many of them were left worse off.

Local authorities’ money for house building in 1987–8 was only a quarter, in real terms, of what it had been in 1978–9. In expenditure terms, however, improvement grants more than offset this reduction up to 1984–5. In other words the Tories were willing to spend on housing, but not in the public sector. Local authority new construction fell from an already low figure of 58,000 in 1981 to a mere 21,000 in 1987. Public sector house building now accounts for only 16 percent of the total. [49] ‘Right to buy’ reduced the council house stock by an estimated one million.’ [50] The private rented sector currently makes up a mere 8 percent of total housing provision, compared to 32 percent in 1960. Housing Associations own approximately 3 percent of the housing stock (500,000 houses), while local authorities own 26 percent (approximately five million properties). Local authorities are still the major source of rented accommodation for those who cannot afford to buy. In 1987 local authorities admitted there were 118,000 households homeless, 91 percent of them in ‘priority need’. Thirteen percent of homelessness was due to mortgage default. Twenty five thousand households were in temporary accommodation, including 10,000 in bed and breakfast. The sheer misery of those in need and the callousness of the response can not be overstated.

Private landlords do not prevent many of the problems that the government associates with local authority housing, namely hard to let sink estates with high levels of vandalism and rent arrears. European housing estates which are privately managed rather than publicly owned face many of the same problems associated with council housing in Britain. This is not surprising, as many of the problems are due to low incomes, not the form of management of the estate.

The 1988 Housing Act was the Tories’ response to the problem. Having won the battle over the right to buy they have moved to dismantle rent control. It took nine years for Thatcher to grasp this particular nettle so long beloved of right wing ideologues (including the young Geoffrey Howe who wrote on the subject in 1956). [51] According to right wing orthodoxy, rent control and security of tenure distort the housing market. They produce rents below the market level, suppressing supply while artificially inflating demand. But the majority of private lettings took place outside the Rent Acts, even before the 1988 act, and market rents were charged. This was insufficient to halt the decline in private landlordism. Quite simply the rate of return is too low on such capital compared to other investments. Other countries with a large private sector, the USA for example, massively subsidise their landlords through the tax system and adopt what one commentator describes as ‘a very relaxed approach to minimum standards’. [52] They rent slums.

The Housing Act stopped short of complete deregulation, which was recognised as too politically risky, but dramatically shifted the balance between tenant and landlord in the landlord’s favour. A new small private rented sector may emerge for the better off, but there is no possibility of the housing needs of the majority being met by private landlords. The only real development in private market renting is a profit making private company with backing from the Building Societies called Quality Street. As the name implies they are only interested in supplying the top end of the market. Thatcher’s policy of relying on home ownership and interest rather than rent to supply the majority of homes is also beginning to falter. High interest rates have increased evictions. House prices have been falling in the south east, ruling out the possibility of selling as a way out of trouble. Home ownership is beginning to look like a spur to militancy as the real level of inflation for many mortgage holders soars above the official level.

Housing is undoubtedly an area where privatisation of provision has been most successful. Even here, however, the way had been prepared by the previous Labour administration’s acceptance of house ownership as the norm. Much has been made of Thatcher’s achievement by arguing that council house tenants are solid Labour voters and that therefore sales represent an erosion of Labour’s voting base. [53] The truth is that while privatisation has provided bargains for some and eroded council house provision there is no direct relationship between a mortgage and a willingness or ability to fight. The argument even a year ago was that it dampened down militancy – the argument now is that it fuels it! Home ownership is not a real source of wealth for workers, since they are tied to their houses. The ideological shift claimed by left reformists appears more dramatic than it really is.

Housing subsidies remain an important element of government spending, although the form that spending takes has changed dramatically. Thatcher is personally committed to maintaining mortgage tax relief, despite the enormous expense. It is unlikely that there will be a flourishing of private landlordism, as the government is unwilling to subsidise landlordism on the American scale. The Housing Act repoliticised housing. In the absence of a large private sector and with the run down of the public sector, buying will continue to be the way large numbers of workers pay for accommodation. This makes housing extremely sensitive to strategies for managing the economy based on increased interest rates. For the poorest and the homeless, whether on benefits or low wages, the prospect is appalling. While housing is not currently a focus for mass protest, ballots will keep the issue alive on many estates. Housing is a key element in the cost of living for most workers and, in the absence of welfare provision to cushion this cost, they confront it directly in the form of wages.

Social security payments go to those who are too old to work and those unable to work, for the maintenance of children of the poor and to those who are unemployed or whose incomes from employment are too low. From capital’s point of view much of this expenditure is without even indirect benefit. While it is to capital’s advantage that the supply of labour power is maintained even when it is not immediately required, it is preferable that this should be done as cheaply as possible. Government and employers are concerned that benefit levels should not interfere with workers’ willingness to sell their labour power. For governments in periods of high unemployment social security payments form a large and largely uncontrollable slice of public expenditure. Policies in this area are likely to be determined by me overriding desire to reduce costs by penny pinching from the poor. The ideological justification for this is provided by distinctions between the deserving and undeserving, the disabled and the ‘scrounger’. The impact of cuts, however, has fallen heavily on all claimants.

Thatcher’s first term saw a whole series of attacks on those dependent on the state. The earnings link was abolished, which meant that pensions and other benefits only rose in line with prices, not in line with prices and earnings (whichever was more favourable). This move ensured that the value of benefits fell as a percentage of average earnings, so that the poor got relatively poorer. In 1980 the ‘5 percent abatement’ meant that unemployment benefit, sickness benefit, maternity allowances, injury benefit and invalidity pensions rose by 5 percent less man the rate of inflation. The justification was that these benefits weren’t taxed. But while benefits were brought into taxation in July 1982 the abatement was not restored until November 1983. Earnings related supplements were abolished in 1980, saving about £300 million. Some of these moves were part of the ideological orchestration of the idea of the undeserving poor. All strikers were deemed to be in receipt of strike pay in 1980, thus cutting benefit to their dependents. In 1981–2 more money was made available to pay 900 extra staff to root out so-called abuse. In 1982 the Social Security and Housing Benefit Act created a new system of housing benefits administered by the local authorities.

Thatcher’s second term saw a major restructuring of social security in the 1986 Social Security Act. The act, however, was not implemented until Thatcher’s third term. It is a draconian piece of legislation mat condemns many claimants to live below even the inadequate official poverty line. Single payment grants have been replaced by loans which must be repaid. If a claimant is expected not to be able to repay a loan, it will be refused. About half of Supplementary Benefit families with children are already in debt. Supplementary Benefit has been replaced by Income Support and Family Income Supplement by Family Credit. There are no free school meals or prescriptions for those receiving Family Credit. Income Support provides no long term rates of benefit, no single payments for special needs, no extra weekly additions for specific needs such as special diets or laundry costs, and a reduced rate applies to all those under 24 years. Instead of the old ‘non-householder’ rate, all claimants will have to pay 20 percent of their rates (or poll tax) and a flat rate element of £1.30 is included in the weekly benefit to cover this, whether or not it does so. In practice many claimants will lose out substantially. ‘Transitional protection’ protects existing claimants, but some will not receive increases for years until their new benefit entitlement is higher than the amount they are already receiving.

The 1988 Social Security Act amended parts of the 1986 act to make matters even worse for young people. [54] Eighteen years rather then 16 years is the new normal minimum age for claiming Income Support. The government is using the legislation to force young people onto YTS. They claim that because YTS is available for 16–17 year olds no young person need be unemployed. Young people are being forced to be treated as part of their parents’ family after leaving education. A new Social Security Bill is going through parliament designed to make it even harder for people to claim unemployment benefit. [55] Claimants will have to demonstrate not only that they are available but also that they are ‘actively seeking employment’. Availability is already a fairly active state, monitored by availability questionnaires and with Restart interviews every six months. These measures have already nearly doubled the numbers of claimants disallowed between 1985–7.

Social security is the least popular area of spending, according to opinion polls. Thatcher has developed the ideological theme of the ‘dependency culture’ and the moral stigma of unemployment in order to isolate the unemployed and justify the harsh treatment of them. She has attacked the very idea of state support by stressing instead individuals and the family. The Tories in their propaganda reject the idea of society affecting individuals. Poverty is presented as an individual failing, thus isolating the poor. Family policy is placed in die section on social security in the 1983 Tory Campaign Guide and Thatcher’s approach is summed up by a speech she made in 1981,

… not only is the family the most important means through which we show our care for others. It’s the place where each generation learns its responsibilities towards the rest of society. [56]

Unlike other areas of welfare spending the social security budget is not cash limited. It rises as a result of demographic changes increasing the number of pensioners and as a result of rising unemployment. Expenditure rose by 36 percent between 1978–9 and 1986–7. [57] It is the largest single element of public expenditure, approximately 30 percent in 1987–8. [58] The numbers of retirement pensions increased by 10 percent from 1979–80 to 1986–7 and increased by a further 1 percent in 1987–8. Unemployment rose sharply in the recession of 1979–81 and the numbers receiving unemployment benefit doubled by 1984–5. After 1984–5 fewer received unemployment as, after a year, people stopped being entitled to contributory benefit and were transferred to supplementary benefit. Registered unemployment itself started to fall from June 1987 when adult unemployment stood at 10.5 percent. The number registered doesn’t reflect the real extent of unemployment. The number of school leavers registering has fallen since 1983 because of YTS. In 1983 men over 60 years old, 162,000 of them, were removed from the register. In all mere have been 20 changes in the way unemployment is counted! The percentage of the long term unemployed increased from 25 percent in 1979 to 43 percent in 1987 and these figures are now to be massaged by die operation of the Restart programme. Nonetheless there have been real reductions in unemployment as a result of the boom. This eases the pressure on the social security budget.

The difficulties of controlling expenditure have not produced fewer attacks in this area. There has been a massive increase in productivity among low paid DSS workers as their numbers have failed to keep pace with the rise in claimants. This has provoked industrial action, but it has not succeeded in reversing die worsening of conditions. Many offices are squalid and pay is appalling. There have also been the numerous attacks on die benefits system. Estimates put me numbers of people living on Supplementary Benefit at about three million more than in 1978. [59] The total number on or below Supplementary Benefit level is estimated at over nine million.

The Tories have aimed at keeping spending under control and reducing levels of benefit in order to widen die gap between those in work and out of work. This is so that benefits do not act as a ‘disincentive’ to work for low wages. One of the aims of replacing FIS by Family Credit and Supplementary Benefit by Income Support is to reduce the numbers of working families being worse off than those claiming benefit. The ‘poverty trap’ can leave a family with four children no better off as gross earnings rise between £73 and £164 when their net spending power remains constant at £125. A family with two children is similarly affected over the earnings range £73–£143 with a net income of £92.38. [60] The problem is, of course, low wages. But the government plans to tackle this by driving down benefits to even lower levels. The Benefits Research Unit estimates that 74 percent of lone parents, 81 percent of couples with children, 99 percent of couples and 89 percent of pensioner couples will lose out under the new scheme.

It is among the poorest sections of the working class that Thatcher’s attacks have been most vicious. Many of the poor, like the elderly and disabled, are particularly vulnerable and it is difficult for them to resist. The Tories had hoped that higher levels of unemployment would restrain wages. It was important therefore that benefit levels were kept so low as to force the unemployed into accepting miserable wages. In fact real wages have risen on average. However the increase in the lowest earning decile from 1979 to 1986 was 3.7 percent (an increase in money terms of about £4), compared to me average earnings increase of 11.25 percent, and increases in the highest decile of 22.3 percent (in money terms over £58). This means that lower wage earners have been doing relatively worse. [61] This is partly the result of me government’s own efforts to hold down wages in the public sector. The low paid in this sector have fared particularly badly. NHS ancillary earnings, for example, have been falling at a rate of 2 percent a year when compared to average earnings. [62]

The government believed that lower benefits would reduce unemployment by forcing people into low paid jobs. This can only be effective if suitable work is available. In fact even where there are job vacancies these tend to be for skilled workers. This has produced an upward pressure on wages as, despite a general fall in unemployment, many of the remaining unemployed do not possess the requisite skills. There are regional variations. The upward pressure on wages is particularly strong in the south east and Midlands where there are skill shortages of professional engineers, computer programmers, machinists, fitters, mechanics, welders, accountants and nurses. The relatively stronger position of workers is producing renewed wage militancy and speculation that the government would welcome an increase in unemployment despite the negative expenditure implications.

From capital’s point of view the old and disabled are unproductive and are therefore only maintained by the state at the lowest level that is politically acceptable. Means testing, now called ‘targeting’, has been a feature of welfare provision since Beveridge. The record of previous Labour governments in this area is poor. Their 1978 review of supplementary benefits left some claimants worse off. Poverty increased between 1974 and 1979, particularly for families with fathers in work. The increase in unemployment has led, under Thatcher, to a massive increase in poverty.

The NHS is the centrepiece of the welfare state. For over 90 percent of the population it provides their only access to health care. It is immensely popular, despite its inadequacies. The well being of workers also concerns the ruling class and this is reflected in the priorities of the NHS. Acute medicine for the able bodied of working age is better funded and includes the most prestigious areas of medicine. Those caring for the elderly and the physically and mentally handicapped remain the ‘Cinderella services’. Health and welfare in these areas have been dominated by the ideological themes of ‘care in the community’. This meshes with individual responsibility and the family in conservative thinking. In practice community care is based on women’s presumed role as carer in the home. Hospital patients are discharged earlier on the presumption of care, whether or not it exists. Psychiatric wards shed patients without proper public provision, leaving the mentally ill prey to totally unsuitable private arrangements.

The Tories have continued to elaborate their ideological themes of private medicine and voluntary effort, but they have proved remarkably cautious when it comes to radical changes. This caution has been reinforced by the abiding popularity of the NHS.

In 1988 well publicised crises of provision in the hospital sector and the nurses’ pay dispute forced the Tories to debate their remedies for the NHS publicly. It was clear that some would have liked to move towards a two tier system based on the American model of massive private health care. This would have left the NHS for those who could not afford health insurance and for unprofitable areas of care, for the chronically sick, the mentally handicapped and the like. Such proposals did not achieve a consensus in the Tory ranks.

Tory policy, in this as in other areas, lacks the cohesion often attributed to it. The health review produced compromise proposals which have totally failed to win support from the medical profession and have caused unease even among some Conservatives.

The main theme of Thatcher’s first term was the commitment to maintaining health spending while producing ‘efficiencies’. The NHS, law and order, and defence were declared protected areas before the 1979 election. The major areas of change were in health service management and contracting out of services. The major event was the health service dispute of 1982. The action lasted from April to November around a claim for 12 percent pay increases and improved conditions, equivalent to a 20 percent increase. Despite massive support the final settlement ranged between 6 and 7.5 percent. The government responded with an Independent Review Body in 1983 for nurses and midwives as a reward to the RCN for their no-strike stance and in an attempt to weaken unity between nurses and ancillaries. They concentrated their attacks on low paid ancillary workers. In 1983 they made the health authorities put cleaning, catering and laundry services out to private tender. They changed the VAT rules to allow a refund where services were contracted out in order to attract private business.

The Tories repealed legislation designed to phase out pay beds. In 1982–3 they restored income tax relief on employer–employee medical insurance schemes for those earning below £8,500. They were cautious about the wholesale adoption of private medicine. A working party in 1981 came down in favour of continuing the finance of health from general taxation.