ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From International Socialism, No.46, February/March 1971, pp.2-5.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

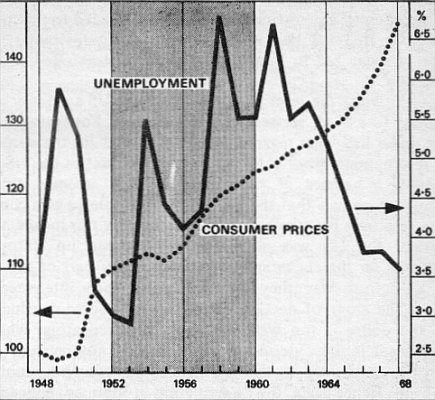

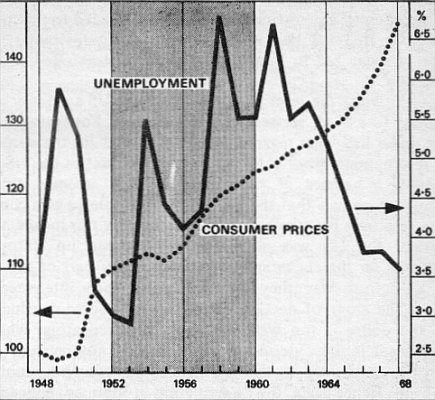

1970 was the year in which inflation on a new, accelerated scale hit every western economy. And in two of these it was of a peculiarly threatening sort. Britain and the US experienced inflation alongside the normal accompaniments of deflation. Rising prices and wages hit them at the same time as stagnant production and expanding unemployment:

Yet the inflation is an outgrowth of the expansion of the last thirty years. It is based on the economic structures that developed during this period. And it was triggered off in part by the tensions within the mainspring that underlay such growth – the permanent arms economy.

The most significant structural change over recent decades has been the massive growth in the size of producing units. National markets are more and more dominated by a few massive concerns. These outgrow national boundaries. Linkages between producers in different countries multiply – either in the direct form of the multi-national company (in the fifties and early sixties US investments in Europe grew sevenfold) – or indirectly as firms grow dependent on foreign components.

These long term trends do not in themselves cause inflation. But they do lead it to rebound through the system at increased speed. Further, they make governmental attempts to dampen the impact less effective.

The modern giants face far fewer constraints than their predecessors when it comes to raising their prices – at least on the home market. Prices are arrived aj not by the free play of the classical market, but by ‘cost-plus’ calculations of either the dominant company or jointly by the few major concerns. So rises in wages, raw material or capital costs (interest rates) can be absorbed and passed on by raising prices. Indeed, the perverse situation might obtain of an individual concern welcoming cost increases as likely to undermine the position ot a more weakly placed rival.

The massive size of concerns also makes it difficult to end of the inflationary spiral. Traditional deflationary methods can have the opposite effect to that intended. Government induced reduction in demand still least to falling markets, increased unemployment of men and resources, reduced use of productivity capacity. But the response of firms is no longer to reduce prices. Idle capital leads to rising costs. Domination of the national markets means that particular concerns can raise prices to recover these and protect profit levels without further reducing sales overmuch.

Parallel changes in the labour market have meant that unemployment no longer automatically reduces the willingness of workers to push for wage improvements. Tightly organised groups of workers strategically placed at the centre of the system are not intimidated by growing unemployment at the periphery. Car workers in Coventry are hardly hit by growing dole queues in Derry or Durham. The very measures governments introduce to make unemployment more acceptable politically – redundancy payment, wage related dole and so on – serve to diminish its impact on the employed.

Even when deflationary measures do hit home, the size of the modern firm forces governments to intervene to counteract the affects of their own policies. Collapse of the really large concerns would have consequences too disquieting to be countenanced. Hence the attempt to prop up Penn Central, and the ready crutch for Rolls Royce. Hence the willingness of the international financial community to rescue the speculative monster, IOS.

However, things rarely reach this stage. The vastly expanded network of international concerns and contacts enables firms and banks to move funds from country to country so as to evade the consequences of deflation. So to be effective deflation would have to be much more severe than at any time in the last three decades.

The dependence of the giant concerns upon an international mobilisation of resources makes it difficult for particular governments to contemplate other traditional responses to inflation. The smooth operation of the system depends more than ever before upon a degree of certainty about predictions of future prices and costs in foreign currencies. This certainty would disappear if governments were to respond to a wave of inflation with a wave of currency revaluations. The long term calculations upon which the orderly growth of big business depends would go haywire with continual changes in exchange rates.

Yet the bulk of capital (although perhaps not the giant concerns with most influence on governments) remains enmeshed in a national system of costs and prices. Inflation at a rate greater than the international average can be disastrous in prising markets from traditional producers (and a lower than average rate of inflation can be a corresponding god-send). In all this there is a contradiction. International capital still operates from national bases. It is intertwined with nationally rooted institutional system, above all with national state structures. And they cannot ignore or evade the consequences of inflation.

The global interrelation of national capitalisms depends, in the last analysis, on the economic and therefore, if necessary, military) power each disposes of. If at any point there is a balanced international framework, this is the product of the interaction of national forces. Effective planning does not extend beyond state frontiers.

An international monetary system underpins the ever greater flows of money and resources from country to country. However, the stability of this depends upon crude interplay of national currencies. Particular states have an interest in maintaining such stability, as the precondition for the international integration upon which growing chunks of capital depend. Inflation is a threat to this integration, because it is a threat to national currencies. Yet the same supernational scale of business operations makes governmental control over inflation even more difficult.

Not to stop inflation is to undermine the international framework upon which an orderly expansion of capital depends. But so extreme are the sorts of measures needed to discipline the international concerns and stop inflation as to also threaten such orderly expansion.

Structural impediments might not matter, were it not that the permanent arms economy has built into it contradictions producing not only inflation, but also creeping stagnation:

1. Since the late forties arms expenditure has stabilised the western economies. Yet there was never a conscious decision by the ruling class to underpin the economy in this way. The growth of arms budgets was a function of intensified military competition between the major powers in particular between the blocs of the cold war. Its level reflected the intensity of this conflict and the contingencies of technological advance in weapon making.

As a matter of fact, the levels of arms spending in the fifties and early sixties was more or less sufficient to stabilise the system. But there was always the possibility of reduced military competition leading to a fall in the level of arms spending below that needed economically, permitting at least a partial resumption of pre-war boom-slump patterns. Likewise, there was always the opposite possibility – that of increased intensity of military competition, leading to a level of arms expenditure too costly to permit a continued normal functioning of the civilian economy.

2. The contradiction between the military functions of arms production and its economic consequences was heightened by the fact that arms production within the western bloc has not been an equally distributed burden. Its benefits (military and economic) have been shared, but not its costs. Arms account for nearly ten per cent of the American Gross National Product and sixty per cent of fixed capital formation there, compared with corresponding figures of 6.5 per cent for Britain, while the Japanese economy, larger than the British, has to pay out only a quarter as much on arms.

In the early post-war period this hardly mattered. The US economy had prospered in a war that brought devastation to half of Europe and Japan. By the sixties, however, the European and Japanese economies were recovering with a vengeance. Although unable to prevent a growing US dominance of the most advanced industries, they could exert sufficient pressure elsewhere to force the US (and Britain) to worry about the way arms spending was forcing up industrial costs, and therefore to curtail it accordingly. Military expenditure has fallen from eight per cent of total western GNPs in 1953 to about four per cent today.

3. The tendency in arms technology has been towards the development of weaponry, the production of which fits in less and less with the needs of the civilian economy. Production of highly advanced missiles provides fewer jobs per unit of expenditure than say, battleship or aircraft production. It also fits less into the technological needs of civil industry: innovations and inventions become relatively more specialised and less useful for non-military purposes.

The overall result of these three factors is that the expansionist effect of the permanent arms economy declines over time. A declining level of arms expenditure of a more specialised sort mops up less unemployment and provides less of an impetus to growth in the rest of the economy.

Yet the inflationary effects of arms production do not disappear simultaneously. It still continues to hog valuable material and skilled labour resources, to the detriment of civilian industry.

So the normal, characteristic feature of the arms economy in its heartlands has been the peculiar combination of inflation (although not at the recent rate) and comparative stagnation.

The middle sixties might seem an exception to this overall picture. After all, the US economy did enjoy average growth rates of more than four per cent for the best part of a decade (compared with little more than two per cent in the previous decade). Unemployment did, albeit temporarily, fall to its lowest level since the Korean war.

Exceptions do, however, sometimes prove rules. The Nixon administration is now setting out to create an unemployment level of about five per cent, even in years of expanison. The US boom of the mid-sixties was brought to a close by deliberate governmental decision as its side effects began to threaten profit rates. The consequences are part of the explanation of the current wave of inflation. And this wave is likely to accentuate the long term trend towards stagnation.

|

The current inflation cannot be explained in terms of any one factor. Several causes have worked to produce a single effect. But all are rooted in the structures and mechanisms outlined above.

1. By 1968 the Vietnam War had long ceased to be a boon for the American economy. True it had increased arms expenditure (by about twenty per cent in 1967 and ten per cent in 1968) and what is more shifted the emphasis from highly specialised ‘strategic’ projects to ‘general purposes’ ones of more benefit to civil industry. The results in terms of lower unemployment and faster growth rates were plain for all to see.

But military expenditure moved beyond the point at which it stabilised the economy to the point at which it began to cut into profit margins. Taxes, interest rates and raw material costs rose as government demands on resources expanded to pay for the war. Workers reacted to upward moving prices with a new level of militancy. The number of strikes was fifty per cent higher than five years before, and the number of ‘man-hours lost’ was twice as high. The war, far from being an aid to the economy became a hindrance.

As the Economist put the matter late in 1968:

‘Some time ago Wall Street switched from its original view that the war was pepping up a tired boom to thinking that it is aggravating every problem of the economy and forcing restrictive action (tax increases and above all tight money and high interest rates) that investors, emphatically dislike. Peace, the street now thinks, would be the best thing that could happen.’ (October 26, 1968).

The US government began both to try and disengage from the war, cutting the absolute level of military expenditure for the first time for years, and to try to cool down the US economy quickly with a cold douche of sharp tax increases and harsh monetary policies.

Here the structural factors we outlined above had thieir effect. Unemployment rose from just over three per cent in 1968 to nearly six per cent today. But prices did not stop going up. Indeed, the rate of inflation accelerated as firms covered the cost of increased excess capacity. Feeling able to pass on cost increases, they were also prepared to pay unprecedented interest rates for the funds needed to tide them over. So the first two years of Nixon’s administration have seen a slight fall in total output and an accelerated rate of inflation.

2. While the internal problems of the US economy were coming to a head, so were its external ones. For twenty years the dollar had been regarded as good as gold for the purposes of international payments. But by the mid-sixties the US was running a balance of payments deficit. It seemed to the European powers that the US was in fact able to gain control over resources by merely printing dollars. By this means, they argued, the US was simultaneously buying up European industry on the cheap and making them pay part of the cost of a Vietnam War they were not particularly interested in.

The story of de Gaulle’s attempts to force devaluation of the dollar is too well known to bear repeating. What is significant is the outcome. The dollar was not revalued, but the US was forced to take its balance of payments problems in hand. Hence again, the de-escalation in Vietnam; hence also, more importantly here, an attempt to curtail the flow of American investment overseas.

In short: the surge of inflation in Europe is due, at least in part, to the long term destabilising effects on the international financial framework of the uneven growth rates of the various western economies – an unevenness built into the very fabric of the modern arms economy.

3. Last, but not least, have been changes in the mood of the working class. The years of the recent inflation have also been the years in which workers everywhere have begun to discover a new militancy.

The most graphic examples of this were the French May events of 1968 when the habit of years of docility and despondency were lost over night. The same infection hit Italy with the ‘hot’ autumn of 1969. Simultaneously the ‘revolt of the lower paid’ was hitting Britain, as resentments accumulated during ‘incomes policy’ and wage freeze took effect. And the US has seen a similar, if unheralded, rise in wage militancy.

It is a purely academic debate as to whether this international striving for improved living standards and conditions was among the initial causes of inflation. But once in motion it has made much more difficult any control of this. Frustrations built up during a period of expansion do not disappear just because governments try to slow economies down. Wage demands are still put in, and conceded, in a context of stagnant production. Existing inflation is accelerated.

This had an unforeseen inflationary impact on Europe. Corporations used the network of international contacts and credit institutions to compensate for the reduced flow of dollars to Europe by an expansion of credit based on the ‘Euro-dollar’ pool – the mass of currencies able with ease to flow from country to country. And for the first time, the biggest drawers on this pool became US businesses trying to evade government measures aimed at reducing the level of domestic credit. So interest rates in Europe began to rise.

More importantly, European governments felt compelled to try and protect their currencies from the impact of massive flows of funds crossing and recrossing frontiers.

Their only protection lay in trying to build up gold reserves, by increasing foreign currency earnings while keeping a check on domestic consumption. A variety of policies were followed. But the result was always the same: export earnings rose while efforts were made to restrict the supply of goods to be bought with them on the domestic market – an inherently inflationary situation.

The current inflation is not the collapse of the capitalist system. It is not 1923 or 1929. Nor is it the end of the expansion western capitalism has known since the war. World trade has been growing at record rates in recent years. In 1971 the US economy is expected to grow by about 4 per cent, although growth rates in Japan and Europe will fall a little. The overall expansion will probably be much the same as in recent years.

Inflation does, however, threaten to upset the framework within which this expansion takes place. Particular governments fear for the competitiveness of domestic industry as costs and prices soar. In the cases of Britain and the US the result in the middle term could be further threats to the international value of the pound and dollar. And so policies are attempted which, for the reasons outlined above, do not end inflation, but do undermine possibilities for future expansion: on the one hand monetary attempts to stop the expansion of demand, on the other threats to physically impede access to markets by foreign competitors.

Yet it is known in advance that such policies can only increase instability, and so they are resisted or carried out half heartedly. After attempting unsuccessfully to beat inflation by forcing industry to stagnate the US government is now attempting to achieve the same goal by encouraging expansion. And the initiative to restrict American imports from Japan with a Trade Bill has been defeated in Congress – for the time being at least.

Overall there is an increasing loss of control by those apparently running the system . They are faced with processes that can only be taken in hand at a rising risk to the future prospects of the system. But not to bring them under control is also to upset these prospects.

Politically the result is increasing indecision and bitter wrangles both within national ruling classes and between them. At home each government is less clear as to the way forward. Internationally, squabbles between western powers can be expected to grow more intense.

The social consequences will be even more pronounced, A rapid acceleration and inflation inevitably causes a breaking of many of the ideological ties that bind workers to the system. If what is involved in trade unionism is a discussion over a two per cent productivity related wage increase for the workers at a single shop, then it is fairly easy for people to think they are all one happy family. This is hardly credible when a hundred thousand workers demand twenty per cent to keep up with a ten per cent price increase. And although the revolutionary left is still small and predominantly middle class, it is more able to intervene in such discussions than at any time in the last three decades. Organised workers can keep up with inflation – but only by discovering a new industrial militancy that can also be the beginnings of a new political militancy.

The determination of governments to try and deal with wage militancy will also grow. Here, it seems, is the one factor in the situation which can be controlled without weakening the system’s general stability. Continual calls for governments to stand firm against wage claims will be met with spasmodic attempts to do so. The class strains in the system, the growing detachment from, if not hostility to, the system by workers will be accentuated.

Internationally, there is a further threat on the horizon which could wreak untold damage to an already faltering expansion. The US government now seems committed to the construction of massive new missile systems. If these go ahead, arms expenditure will soar once again, and in precisely the way which is most detrimental to the civilian economy. Inflation would be given an unprecedented boost. Yet the new investments involved would be in projects more specialised than ever before, with less spin-off to the rest of industry and with less effect on productivity and unemployment. The present troubles will reappear on a much enhanced scale.

In any case, the present offers little to cheer up British capitalism. All the factors that cause concern internationally are accentuated here by the particular problems of British industry. Government policies over the last six years have done little to solve these. Incomes policy and wage freeze, devaluation and import controls, above all the cutting down on economic growth to a minimum, have produced a small balance of payment surplus. (If, indeed, it was such policies and not unrelated factors like the fall in primary produce prices, that produced this balance). But the cost in terms of unrealised potential production increases has been enormous. Yet any real expansion in the near future threatens side effects that would cut into the surplus and threaten the pound once again.

The rate of inflation in Britain this year is likely to be higher than anywhere else. Real expansion could push this to unforseeable heights; but stagnation, or even further recession, will not stop it either. And so the pattern of the past years is likely to continue: the slowest growth rate in the west, a declining share of world markets, and periodic anxieties over the pound producing the pound producing policies that can only aggravate these difficulties.

Against this background the only way the Tories can make any leeway is to cut back on the gains the organised working class have made during three decades of capitalist expansion. The Tories ruled throughout the fifties without trying to weaken fundamentally either the unions or the welfare state. Now such policies seem the only ones that can dampen the long term decline of British capital.

ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 6.3.2008