ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From International Socialism, No.43, April/May 1970, pp.15-20.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

In the last 10 years the long post-war boom in the Western economies has begun to falter and run short of steam. The causes of the slowdown have been analysed elsewhere [1], but one of its obvious effects is the re-emergence of permanent pools of unemployment and of areas of economic depression which fail to respond to substantial infusions of government aid. As these depressed areas exist within a general context of continuing expansion and rising prices, where certain types of skilled labour are in short supply, and where competitive pressures boost up the rate of productivity, the resultant mixture can be highly explosive, especially where the section of the labour force which is excluded from the general prosperity is also a racial or cultural minority. The overlapping of frustrated expectations with the results of uneven capitalist development has already left its mark in the ghettoes of the United States and in Northern Ireland.

Depressed areas are characterised by the presence of relatively high unemployment and/or low income levels. They are now an increasingly obvious feature of most of the mature capitalist economies.

In the USA, for example, there are 900 ‘distress areas’ with a combined population of 55 million people. They range from the traditional declining industries – New England textiles, mining, agriculture, fishing and timber – to more recent casualties of technical change like the Pittsburgh steel industry, and now even California has its distressed areas, as its defence industries fail to generate sufficient employment to match the high rate of immigration from other states. What can lie behind the bland term ‘distressed area’ may be gauged from this terse description of the problems of the Appalachian region:

‘The land is ravaged, the waters are being poisoned by acid mine drainage, the miners are unemployed and unsuited for alternative occupations, there is no indigenous entrepreneurship, and public capital is almost totally lacking.’ [2]

Europe also has its share of such areas. The Aquitaine region of south-western France has remained under-developed after 15 years of government aid. Even the development of a highly capital-intensive industrial complex on the huge natural gas field at Lacq failed to generate any further industrial growth. In 1955 the turnover of Aquitainian firms was 2.5 per cent of the national total; in 1964 the percentage declined to 2.4 per cent. In addition the attempt to modernise agricultural production foundered on the poverty and fragmented land-holdings of the peasants.

The whole of southern Italy constitutes another area which has proved intractable to government development policies. After 20 years of financial incentives for private industry and the establishment of several large State-owned plants, the employment situation of the region is deteriorating again. [3]

Of more direct relevance to the British situation is the Walloon (French-speaking) area of Belgium, which has been affected by the rundown of its coal and metal manufacturing industries. Since the mid-1950s its rate of growth of output has been half that of the rest of the country, and its labour force has grown at one-eighth of the pace of the neighbouring Flemish area. It was designated a ‘Development Area’ in 1959 and the usual financial incentives offered for firms to move there. Despite this, the area continues to decline; investment and wages are lower in the Walloon area than elsewhere, and this differential was an important factor in the bitter miners’ strikes which broke out there early this year.

There is nothing remarkable about unevenness of development, both between regions and different industries in a capitalist economy, nor for the relative positions of regions and industries to change over time. In fact, unevenness is the normal condition in an unplanned economy; but it is the uncontrolled speed of change and the concomitant waste of human and material resources which characterises ‘progress’ under capitalism. Up to 1914 the London area and southern England was most heavily affected by recession; but after the First World War the regional balance shifted abruptly as the capital goods and staple export industries were devastated by the post-war slump. Between April 1920 and April 1921 unemployment increased from 2 per cent to 18 per cent, and Scotland went from the bottom of the regional unemployment table to second from top, behind Northern Ireland. [4] At the depth of the depression the former boom industries of the 19th century suffered a catastrophic decline; 1932 unemployment rates were 62.2 per cent for shipbuilding, 33.9 per cent for coalmining, 28.5 per cent for cotton, and 43.5 per cent for iron and steel. By 1935 the share of net output produced in the old industrial regions [5], had shrunk from 50 per cent in the early 1920s to 37.6 per cent.

In fact it is precisely this past experience of regional concentrations of high unemployment that makes governments so sensitive to the problem of regional imbalance. When a monetary squeeze combined with the bad weather of 1962/63 to push unemployment over 7 per cent in the Northern Region, old memories were stirred, and provoked a sharp political response. A massive and militant lobby of Parliament was organised by the trades councils, which with its overtones of the hunger marches of the 1930s, provided the stimulus to all the subsequent regional development activity of both Tory and Labour governments.

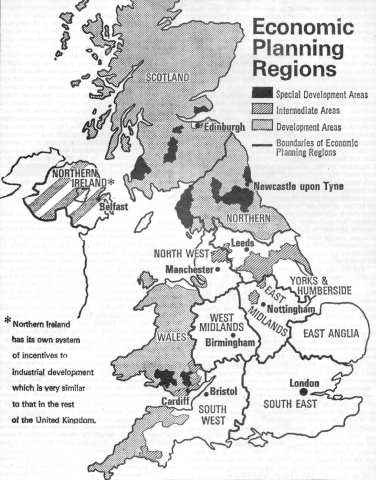

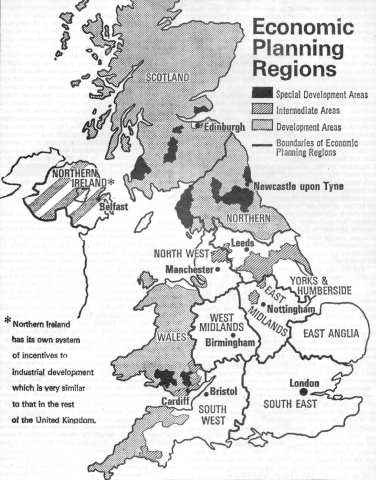

The problem did not appear to be very formidable in the early 1960s. True, the unemployment rates in what came to be designated as the Development Areas (see map) were now two to three times the national average, as they had been in the 1930s. But national rates of 2-3 per cent bore no comparison to the range of 9-22 per cent experienced in the pre-war period.

|

Furthermore, the economic planning levers in the hands of the government had multiplied beyond recognition, and had already been tested in practice. In the period of readjustment immediately after the Second World War the government had successfully directed industry to the depressed areas where excess capacity had re-appeared with the cessation of wartime production. Even though the government allowed the clause in the 1945 Distribution of Industry bill which would then have given the Board of Trade powers to prohibit new factory building in certain areas to be deleted, it was able to channel more than two-thirds of all factory moves to the development areas, thanks to the general shortage of existing factory space elsewhere.

But the re-emergence of depressed regions has proved to be a more intractable problem, and since 1963 expenditure on regional employment policies has increased tenfold as the government has developed an unprecedented range of new financial inducements. These now include:

- Investment grants of 40 per cent of the cost of new plant and machinery in development areas (20 per cent elsewhere). Until 1966 government investment allowances were conditional on the creation of new employment. This provision was excluded from the Industrial Development Act which introduced investment grants.

- Building grants of between 25 and 35 per cent of the cost of factory construction, or the provision of government-built factories at low rents.

- Regional Employment Premiums of 30/- per man employed in manufacturing industry in development areas – guaranteed to 1974 at the least. Swan Hunter, the Tyneside shipbuilding combine, increased its profits last year by £1,500,000 in REP payments.

- Under the Industrial Expansion Act of 1969 further support was offered to private industry for projects which they were unable or unwilling to finance themselves, and which were in the national interest. Upper Clyde Shipbuilders have received generous handouts from this source.

- Seventy-five per cent capital grants for the clearing of derelict land in development and ‘intermediate’ areas. The development areas, with 20 per cent of the insured population, have half of all derelict land.

- The extension of restrictions on industrial development in the south and midlands. Any development in these areas of more than 1,000 sq.ft. of floor space (5,000 sq.ft. elsewhere) now requires a BOT certificate.

The total cost of regional assistance to industry for the financial year 1968/69 was £265 million. [6] This vast expenditure is a measure of the importance that regional employment policies have assumed for the Labour Government. They dccupy a crucial place in what has become a general strategy for the re-structuring of British industry at the expense of the working class. The strategy takes the following form:

The United Kingdom Government can be seen as working strategically on two lines in order to achieve more harmonious industrial relations and the best possible use of the nation’s manpower resources. On the one hand, a number of manpower policy reforms are undertaken, which along with their social value should reduce resistance to economic and technical change and psychologically pave the way for a once-and-for-all elimination of old rigidities. On the other hand, efforts are made to intervene directly in the industrial relations system with a view to reducing unnecessary strife and indirectly achieving a better functioning of the labour market. Obviously the two strategies are mutually supporting. (OECD Observer, August 1969, p.17.)

The appearance of rational deliberation is deceptive, since this strategy is derived from a series of responses to the balance of payments crises of recent years. Nevertheless a total strategy has now emerged and the labour movement needs to become aware of the challenge it faces.

In the forefront is the apparatus of the incomes policy and productivity agreements, which provide both the ideological background and the means to the wholesale reorganisation of British industry. On the one hand the State groups together through a series of sponsored mergers those capital units which have export growth potential, based normally upon advanced technology. The infrastructure and resources are supplied by the State too, by the expansion of higher education, extension of university and government research facilities to industry, cheap basic materials from nationalised industries, modernisation of communications and ports, and not least by substantial injections of finance.

Direct public assistance to private industry rose from £325 million in 1964 to £1,192 million in 1968. [7] On the other hand, someone had to foot the bill. Taxation as a proportion of gross national product has increased from 33.5 per cent to 40.75 per cent [8] in the last five years, and as Jim Kincaid demonstrated, the main burden has fallen upon the working class. To this needs to be added the cost of rising prices, a steady half-million unemployed, and between £5,000 and £12,000 million of lost production through four years of continuous deflation. All dedicated to the ultimate irrational goal of keener competition in the world markets.

Hence the need for manpower policies to blunt resistance to this onslaught on working-class living standards and working conditions. In addition to the regional employment measures outlined above, there are three other elements to the manpower strategy of the government: redundancy payments, the earnings related unemployment benefits, and retraining schemes for redundant workers.

In 1968 an average of £230 was paid to 264,000 workers under the Redundancy Payments Act provisions. This one piece of legislation has been invaluable to employers in the productivity drive. The OECD was duly impressed:

’it seems to have had a major influence upon trade union attitudes to redundancy and technical progress; in place of the former insistance on no redundancies under any circumstances, or the generally observed rule of “last in, first out”, a much more flexible attitude is now found’. [9]

It is now common practice for long-service workers to volunteer for redundancy as they stand to receive most in severance payment. In fact a pattern of ‘first in, first out’ has developed. But the older the worker the longer he can expect to remain unemployed. Fowler [10] found that men aged 55 and over remained on the unemployment register five times longer than men in their twenties.

The earnings related unemployment benefit has a similar dampening effect on resistance to redundancies. Since 1966 a married worker with two children earning the national average wage can expect to receive about 60 per cent of this level Of income on the dole. Although the increase itself is to be welcomed, like all selective welfare measures it has a socially divisive effect. The unemployed are split among themselves, and lower-paid workers become extremely resentful of the ‘affluent unemployed’.

Retraining of redundant workers is provided for in the Industrial Training Act and by the establishment of Government Training Centres (GTCS). These provisions are a key element in the current mystifications which envelope the government’s manpower policy, for instead of depressing old-style unemployment, the victims of shake out are in theory in a state of redeployment. (One in five have been redeployed for a year or more.) In practice the Industrial Training Boards devote their vast resources to the training of apprentices, foremen and managers, not’ to redundant workers; and the net effect of the ITBS will be to reduce job opportunities, not increase them. Already the engineering apprenticeship has been reduced to four years, with no compensating increase in the intake of apprentices, and traditional job demarcations disappear under the new training scheme. Apprentices in the metal trades in the shipyards are now trained as ‘shipbuilders’ who will be able to turn their hand to plating, caulking, welding or plumbing as required. As for the GTCS, their 10,000 places are not likely to make much impression on half a million unemployed. Of the 2,664 men paid off by February 1969 at AEI Woolwich only four found places in GTCS. The budget allocated to retraining by the government is sufficient refutation of the myth of redeployment. In 1967 the retraining programme received £1.5 million, as against the £50 million of redundancy payments spent on ‘shaking out’ prospective customers.

Responsibility for manpower planning and control is exercised through a bewildering variety of organisations; the regional planning boards and councils, the National Economic Development Council with its ‘little Neddies’, the Central Training Council and Industrial Training Boards, the Prices and Incomes Board, the Manpower and Productivity Service of the DEP, and, the latest addition, the CIR. In this sphere at least, the government’s employment policies have born fruit.

And yet the results of this immense bureaucratic endeavour have been remarkably meagre. The Development Areas remain relatively underdeveloped, and their high rates of unemployment persist. The gap between them and the rest of the country has narrowed slightly it is true, but this is attributable to the general rise in unemployment in the last three years. Other results are evident; the proportion of jobs (measured in terms of approved industrial development certificates) going to development areas has doubled in the last 10 years. With 20 per cent of the insured population they are now getting over 50 per cent of IDCs. But set against this is the fact that employment generally is increasing much slower than 10 years ago (in fact it has fallen 0.2 per cent since 1963), and that the rundown of declining industries has accelerated. Thus, whereas the development areas had a small net gain in male employment from 1951 to 1961 of 36,000 (they lost over 600,000 people through migration in the same period), this had turned into a net loss of 19,000 for the years 1961/66. A comparison in terms of male employment alone reveals a continuing trend against the old industrial areas, whereas female employment is growing as briskly there as it is in the south. Hammond [11] records that the proportion of net additional male jobs going to the South East region (including East Anglia) increased from 63 per cent in the 1950s to almost 70 per cent in the 1960s.

The Hunt Report [12] estimated that the government’s regional policies could lead to the creation of an extra 100,000-150,000 jobs in the Development Areas over the next five years. The Northern Economic Planning Council, however, forecast that the Northern Region alone would require more than 100,000 new jobs between 1966 and 1971, just to maintain the present level of employment.

There are some obvious contradictions in present development programmes which account for much of the failure to solve the problems of the declining regions. With one hand the government seeks to attract manufacturing industry to the north – whereas employment is increasing primarily in service industry and the white-collar sector – while with the other hand it boosts unemployment through deflation and the encouragement of rationalisation. As the basic industries of the development areas are the most susceptible anyway to rationalisation and automation, the net effect is counter-productive. Automation is also encouraged by cheapening capital investment in development areas with government grants. The chief beneficiaries – oil refineries, aluminium smelters, chemical plants and the like – make impressive prestige projects but provide very few jobs, e.g. Shell’s investment of £225 million in its petro-chemical plant on Merseyside will create only 1,200 jobs. Nor is there any evidence for the belief that they will act as growth centres for subsidiary industries. In the era of monopoly capitalism backward areas within industrial countries face similar obstacles to economic development as backward areas outside. The existence already of huge capital-intensive firms in the market is the greatest barrier to the development of small-scale local industries. Thus, the expectation that the transplantation of the car industry into Scotland would lead to the growth of Scottish-based component has not been fulfilled. All that happens is an expansion of production in the existing component plants in the Midlands.

And yet the Development Areas do offer real advantages for private industry (nationalised industries do not qualify for the subsidies). Professor T. Wilson has estimated that a good many firms in the development areas have as much as half their capital outlay covered by official grants and loans, and some may have more. [13] The combined effect of all forms of development area aid amounts to 5 per cent of the total costs of an average firm. In view of this it seems pertinent to ask why the majority of firms are not moving north – especially as the average British factory is 40 years old, and much of the capital equipment equally in need of renewal.

The answer is that there is an ‘imponderable’ in all this. It is all very well having lowered labour costs, but it may be a question of say export orders which have to be settled over a round of drinks with a foreign buyer who arrives through London airport. He may be flying on to Amsterdam or Zurich and may not have the time to get up, for example, to County Durham. Then there is all the reason in the world (despite the fact that it is not quantifiable) to consider this personal issue which may involve the difference between a gained order and a lost one. It may be that the industrialist may think this, even if it is not true, and still will not move to a development area. I think this is the final irrationality in location decisions, that it is not just a question of the wife liking the shops, or that the factory is near a nice golf course in the Home Counties, but it is the fact that the industrialist has a hunch that he might go bust and so he has not basically got the resources to make such a dramatic decision to move. (Contribution by Professor Hall to Conference on regional planning in Britain. [14])

The response of Professor Hall’s cautious capitalist reflects not only the irrationality of the system but also where the power lies within it. While the industrialist decides to stay put because of a hunch, whole communities are destroyed because it is not deemed ‘economic’ to site new factories in old pit villages. Nor is it only in the Western economies that the personal preferences of the top people determine planning priorities, as the following anecdote, again from Professor Hall, makes clear:

I was being shown round Moscow once by a member of the Moscow city planning department and he said: ‘in capitalist countries you have the problem of land speculation and all private office blocks want to be in the centre of the city with enormous resultant congestion problems. In Soviet Russia in the revolution of 1917 we abolished the profit motive and all speculation in land ceased’. Then he paused, but continued: ‘in spite of this, all the State offices want to be in the centre of Moscow just like capitalist offices. We had a brilliant idea; we decided to decentralise them all together because they said they all wanted to be near each other, and they were related to the Kremlin. We can’t move the Kremlin because it is historic, but we decided we could move all the other offices. We proposed to move them to an enormous site four miles out near the University in the south-west of Moscow, and they will get all their inter-linkages and they will be perfectly satisfied there. So we reserved them this enormous piece of land you see here’, and he pointed to the largest open space I have ever seen, with a single building in the middle, and he said, ‘the only trouble was that none of the offices would move; in fact the only office we managed to have any success with is the one you see over there in the middle of this site, which is the Embassy of the Peoples Republic of China. [15]

The emergence of a permanent pool of half a million unemployed in the midst of inflation and areas of labour shortage presents the labour movement with a new set of problems.

But for the unemployed themselves the problems are familiar; social isolation, frustration, reduced material circumstances, and demoralisation. A study of redundant miners in the Houghton-le-Spring area of Durham [16] revealed that 88 per cent of the redundant men were over 45, and that three years after they were paid off only 22 per cent of them had found jobs. The older the man the slimmer his chances of working again. Of those who did find jobs only 12.5 per cent obtained semi-skilled or skilled work; the remainder were employed as heavy labourers. In their new jobs the majority earned less and worked longer hours than they did in the pit.

For those on the dole the first problem was the drop in income – 40 per cent for superannuated officials, 30 per cent for daywage men, and 70 per cent for pieceworkers. Beer, cigarettes and sociall life were the first economies, but several wives reported that they had not roasted meat since the last of the redundancy payments, and one husband said how sick he was of ‘stews without meat’ and that dogs of his friends saw more meat in a week than he did in six months. In addition to the fall in income most men had the additional cost of having to pay rent for the first time on their colliery house, and they lost their free coal. Add to this the boredom of men used to an active working life: ‘we’ve idle hours by the dozen but we can’t afford to do anything with them but talk, walk and watch TV. ‘I can’t stand idleness, but where do I go from here at 62?’ – and it is not surprising that it doesn’t take long before men become apathetic and spiritless.

In the pre-war depression years this demoralisation was partly checked by the agitational work of the National Unemployed Workers’ Movement. The NUWM was led by Communist Party activists like Wai Hannington and Harry McShane and without this political link the movement would never have risen above the level of a charity organisation, completely isolated from the organised labour movement. The distinctive form of activity developed by the NUWM was the great hunger marches on London, which ensured that the unemployed did not remain invisible and politically impotent. Hannington assessed their value in this way:

One cannot judge such activities as hunger marches simply by the standard of whether an interview with the government took place, or whether definite concessions were made at the time. One has to consider the cumulative effect of the propaganda conducted by the marches. Through town and village, on all the main roads, the marchers had driven home into the minds of millions of the population the tragedy of unemployment and the failure of the government to grapple with it or to relieve its victims. [17]

Without the linkage and political perspective provided by a revolutionary working-class party, there is little that can be done to rally the unemployed workers; and no such party exists at the moment. Therefore the onus of resisting unemployment must fall upon the trade unions and their struggle against redundancies at the point of production.

The shop-floor organisations developed by the British workers over the past 30 years have a good record of successfully resisting temporary lay-offs on a factory or shop basis. But opposition to closures and permanent reductions in the labour force through technical change has led to no victories; nor in a capitalist society could it be otherwise, for the right to hire and fire and freely dispose of property like factories is central to the whole system. At best there have been some good holding actions and compensation agreements. The majority of the following examples are in fact taken from the experience of the American trade union movement which has been facing this type of problem for much longer.

Four basic strategies for dealing with redundancies have been developed, around the issues of

|

Natural wastage varies considerably from industry to industry; and where it is high as in municipal transport, the labour force can be reduced very rapidly. Thus the New York City subway reduced its labour force by 7,500 over five years by natural wastage alone. Where the rate of wastage is left unspecified management is given a free hand to boost the ‘natural’ rate by judicious harassment. An alternative to this form of increased wastage is an induced wastage rate above the normal level via negotiated incentives for early retirement. The Coal Board operates a system of ‘cushioning’ benefits of this order for men of 55 and over. Perhaps the most far-reaching agreement of this kind was that negotiated by the US National Maritime Union which was faced with the prospect of a 25 per cent reduction in the manning of ships. Under this agreement any seaman with 20 years’ service, regardless of age, could retire on full pension. Nevertheless, in all these cases premature retirement involves a sharp drop in the level of a worker’s income.

Work-sharing is the traditional trade union defence against temporary lay-offs, but it cannot cope with a permanent reduction in manning. Reducing the working week, on the other hand, is more effective, but in Britain seems to take an average of two or three decades to achieve. Employers’ resistance is no less strong elsewhere; but there are occasional breakthroughs. The New York Electricians did succeed in reducing their working week from 30 to 25 hours. It was hoped that the shorter hours would lead to the creation of 1,600 new jobs. In fact only half that number materialised through increased overtime working and productivity. In fact, the union was forced to impose an overtime limit of 20 hours per week even to secure the employment increase they did. The reduction of the working year is another device tried in the USA to combat the reduction of employment. In the steel and aluminium industries workers with the requisite amount of seniority get 10 to 15 weeks’ extra holiday once every five years. Although the extra holiday is an advance in itself, it has not succeeded in generating a significant number of new jobs.

The problem with guarantees of job security or income, such as the guaranteed annual wage, is that they are only likely to be won where they are superfluous. The exception is where they are traded for stiff productivity concessions; once they have been bought the renegotiating of the guarantee may become an uphill task. An example of a tin trophy was the guarantee of security and income signed by the Kaiser Steel Corporation and the United Steel Workers, under which any worker displaced by technical change would be placed in an employment pool where he would be guaranteed payment for 40 hours. In the first nine months of the agreement only one worker was placed in the pool – and he was only there for three hours!

Finally, the United States offers an interesting example of a retraining agreement on automation. Under an agreement negotiated by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers with the International Good Music Co., a trust fund was established for the retraining of workers displaced by the introduction of automated equipment, financed by 5 per cent of the receipts of the sales of that same equipment.

These examples probably indicate the limits that purely trade union activity can reach faced with the challenge of redundancies through technical change, for even though the working class displays ceaseless creativity and ingenuity in waging the class struggle, it cannot defeat the threat of redundancy and unemployment without bursting through demarcation lines of trade unionism. Defensive strategies implicitly accept the employer’s right to dispose of his property freely. It is when this right is challenged politically; when we assert that the factories are ours, that we eliminate the dole queue once and for all.

1. M. Kidron, Western Capitalism Since The War, London 1968, especially Part One. Joel Stein, Locating The American Crisis in IS 41.

2. Benjamin Chinitz, The Regional Problem in the USA, one of the contributions in Backward Areas in Advanced Countries, edited by B.A.G. Robinson, London 1969, from which most of the information in this section is taken.

3. ‘In the Latium region, where in 1963 there were 393,000 industrial jobs, there were 30,000 less in 1967. In Calabria, 157,000 jobs in 1962 had shrunk to 146,000 in 1967. In Sardinia over the same period, 107,000 jobs had been reduced to 67,000.’ Andrea Savonuzzi, Italy at the Crossroads, IS 40.

4. The ranking of regions in terms of highest levels of unemployment was: (a) in 1912-14, London, Ireland, S. East, S. West, Wales, N. East, Midlands, Scotland; (b) after 1921, N. Ireland, Scotland, Wales, N. East, N. West, Midlands, London and S. East. From the Economic Journal, December 1969, Survey of Regional Economies, by A.J. Brown.

5. S. Pollard, The Development of the British Economy, London 1969.

6. Provisional estimate. DBA Progress Report, No.55, August 1969.

7. Public Money and Private Industry, Barclays Bank Review, August 1969.

8. Jim Kincaid, Incomes, IS 37.

9. Manpower Policies and Problems in the United Kingdom, OECD Observer, August 1969, p.16.

10. R.F . Fowler, Duration of Unemployment, Studies In Official Statistics, Research Series No.1, 1968, HMSO.

11. E. Hammond, Analysis of’Regional Economic and Social Statistics, University of Durham, Rowntree Research Unit, 1968.

12. The Intermediate Areas (Hunt Report), DBA, Cmnd 3998, 1969.

13. Professor T Wilson, Finance for Regional Industrial Development, Three Banks Review, September 1967.

14. Regional Planning in Britain, proceedings of the Northern Universities Geographical Societies Conference in Hull, 1969, p.31-32.

15. Ibid., p.32.

16. J.W. House and E.M. Knight, Pit Closure and the Community, University of Newcastle, Department of Geography, December 1967.

17. Wal Hannington, Unemployed Struggles, 1919-1936, p.199.

18. Most of the information in this section is taken from Shultz and Weber, Strategies for Displaced Workers, and W.W. Daniel, Strategies for Displaced Employees, PEP January 1970.

ISJ Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 28.2.2008