Figure 1

IMR Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From Irish Marxist Review, Vol. 6 No. 19, November 2017, pp. 37–49.

Translated by Chun Kyung nok.

Copyright © Irish Marxist Review.

A PDF of this article is available here.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the ETOL.

At the time of writing this article, tensions surrounding the Korean peninsula show little sign of subsiding. Koreans are coming to terms with the possibility that their country has now become the world’s most likely site of a nuclear war – in a region, moreover, that has emerged as the center of global capitalism.

Only a quarter century ago, North Korea possessed neither nuclear weapons nor even medium-range missiles. Today it has undertaken six nuclear tests (the latest with an H-bomb) and boasts ICBM-launching capability. While many experts are unsure of its capability to strike the US mainland, many consider it as at least capable of hitting cities of US allies such as Tokyo and Seoul and US military installations in Okinawa and Guam with nuclear weapons.

Taken out of context, North Korea’s ‘provocations’ can therefore seem like the primary cause of the instability in Northeast Asia and the Korean peninsula today.

There is no doubt that Pyongyang’s nuclear program is terrible news, but it has to be seen against the background of the rivalry taking place among the world’s top three economic powers surrounding the Korean peninsula, themselves engaged in a nuclear arms race. The North Korean nuclear standoff is the cumulative product of policies enacted by successive US governments to maintain US hegemony in East Asia since the end of the Cold War. In essence, US efforts at non-proliferation invited a blowback in the form of nuclear proliferation to North Korea. It also has to do with the way the Korean peninsula has become the frontline of inter-imperialist rivalry. In other words, instability in the Korean peninsula today is rooted in the imperialist world system.

To understand the Korean situation, it helps to first look at a map. (See Figure 1.) The Korean peninsula is at the eastern fringe of Eurasia, joined to its North by China’s northeastern province and Russia. The border between China and North Korea, in particular, spans 1,500 kilometers and include the lengths of the Amnok/Yalu and Duman/Tumen rivers. Beijing is two hours away by plane; the southern tip of the peninsula is close enough to Japan that Tsushima is visible from the southern coastal city of Busan.

Figure 1 |

These geographic conditions made the peninsula a prime target for competing imperialist powers ever since western powers set foot in East Asia in the 19th century. The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 saw the two powers clash over Manchuria (China’s northeastern province) and the Korean peninsula. Japan, a British ally at the time, sought to curtail Russia’s march southward, whereas the latter sought to seize Manchuria and secure a warm-water port in the Korean peninsula. The war was preceded by a breakdown of talks where the two sides tried to negotiate a plan to partition the peninsula around the 38th parallel. Japan, upon emerging victorious, annexed the entire peninsula in 1910 and subsequently used it as staging ground for its push into China. The 35 years of Japanese colonial rule that followed was a terrible experience for the Korean people, and when Japan was defeated in the Pacific War in 1945 freedom seemed to be within reach at last. But then entered US troops in the South, and Soviet troops in the North, partitioning the country around the 38th parallel.

Both the US and Russia saw the Korean peninsula as a land of strategic importance, a must-have in their quest to secure a sphere of influence in East Asia. To Washington, Korea was the forward base from which to defend Japan and the Pacific. The USSR likewise entered the peninsula with its own imperialist designs. The two imperialisms then established amenable states on either side of the 38th parallel, crushing all manner of indigenous resistance in the process.

The Cold War ignited a horrific war in the Korean peninsula in 1950. North Korea’s Kim Il-sung, with Stalin’s approval, launched an invasion to unify the country. But soon the US and then China entered the fray. The war dragged on for three years, killing over three million, mostly civilians. The US considered the nuclear strike option on multiple occasions during the war, with Pyongyang as their candidate for a second Hiroshima. In the event a nuclear strike didn’t materialize, but the indiscriminate aerial bombing of the entire peninsula achieved much the same result (especially in the North, where no building was left standing). The Korean War was an inter-imperialist proxy war that in many ways epitomized the horrors of the Cold War.

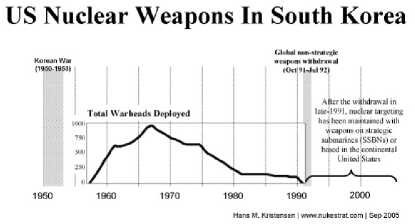

Eventually the frontline stabilized around the 38th parallel where it all began, and an armistice was signed in 1953. The two Koreas went near the brink of war multiple times since. US forces were stationed en masse in South Korea who brought with them nuclear weapons (at one time counting nearly one thousand warheads, see Figure 2), in breach of the armistice. The nukes were withdrawn in 1991 with the end of the Cold War, but the US still rehearses nuclear war scenarios in the peninsula through large-scale joint annual military exercises with South Korean forces.

Figure 2 |

The rulers of North and South have been in a permanent state of preparation for a second Korean War. Decades of competitive arms buildup has turned the so-called demilitarized zone (DMZ) into an area with the highest concentration of conventional weaponry in the world.

Under pressure of military competition across the DMZ, the two Koreas consolidated dictatorships at home. In the North, Kim Il-sung and his confidants purged rival factions in the bureaucracy, and played a balancing act between Russia and China throughout the Cold War, focusing on industrial development led by heavy industry. In the South, successive pro-American dictators repressed labor movements and promoted state-led industrial development.

In such a way rapid industrialization occurred on both sides of the 38th parallel, creating independent centers of capital accumulation. But this also meant the creation of working classes, the gravediggers of capitalism, on a massive scale in both countries. In South Korea, mass revolt broke out in 1987 and brought about the transition to bourgeois democracy. The working class was at the center of the revolt.

As the Cold War drew to a close, the peninsula faced a more fluid situation. But the end of the Cold War didn’t lead to a thawing of relations that so many Koreans had yearned for; instead it signaled the beginning of new instabilities.

The fall of the East enhanced Washington’s political and military clout in the world, but its economic position was in relative decline: The massive growth of other capitalist powers like Germany and Japan, along with the rise of newly industrializing countries, was shifting the geographic distribution of economic power. US rulers became concerned about their ability to maintain their dominant position in the international order. US imperialism needed a new strategy.

Maintaining dominance in East Asia was also a major concern. Washington’s key strategy in this regard was to compel Japan to submit to US leadership, but the US-Japan alliance faltered into the mid-1990s. With the demise of the USSR as the common enemy, China was now also a potential competitor to the US.

The Gulf War of 1990–91 was an occasion for US rulers to showcase its military might to the rest of the world, impressing upon other rulers that the stability of the world economy ultimately rested on US power.

In the eyes of Washington, North Korea seemed fit to play the part of the East Asian equivalent of Iraq, a new bogeyman that required US intervention. North Korea at the time perfectly fit the image of a rogue state, estranged from USSR and behaving recklessly.

North Korean state capitalism faced serious crises from within and without in the 1990s. Its economy was ahead of its southern neighbor until the 70s, but its model of autarkic development hit upon its limits, and the economy entered a downward spiral in the 80s. The fall of the Eastern block dealt a decisive blow, exploding the economic gap between the two Koreas. The trend has continued to the present day: South Korean GDP today is estimated to be 45 times that of the North.

Also unsettling to Pyongyang was the fact that USSR/Russia and China established diplomatic ties with South Korea while the North had yet to do so with the US. North Korean rulers saw this development as a major security threat. Indeed, it was in 1990 when USSR notified its intention to open diplomatic relations with Seoul that North Korea first indicated to USSR its interest in developing its ‘desired weapon’.

Nonetheless, North Korean rulers did not move straight toward developing nuclear weapons. In order to secure resources for economic relief, Pyongyang made repeated overtures to Japan, the United States, and other countries in the West. In 1992, Kim Il Sung said, ‘I want to go fishing in the United States and make friends.’ In 2002, his son Kim Jong Il met Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi and said, ‘I want to sing and dance with President Bush all night.’

It was Washington that slapped the hand extended by Pyongyang. In 1991, when North Korea came close to establishing ties with Japan, the US stepped in and derailed the process. It then accused the North of developing nuclear weapons in its nuclear facilities in Yongbyon. Tensions began to build up.

The US blew North Korea’s ‘threat’ out of all proportion, but it wasn’t North Korea itself that worried the US. Picking on North Korea’s nuclear program was a means of furthering Washington’s policy of nuclear non-proliferation. North Korea happened to be a convenient target to be made an example out of, to send a message to other powers that might be tempted to challenge the US’s nuclear supremacy in a post-Cold War world.

Pyongyang sought to placate the US with a flurry of concessions and serious proposals, none to be taken seriously by its counterpart.

By the summer of 1994, the US was pounding the North with all manner of threats and preparing for military action. The Clinton administration reviewed a plan to strike North Korean nuclear facilities and prepared massive reinforcements of US troops in South Korea as a preliminary move. This decision entailed the risk of war in the peninsula. The US Ambassador to Korea at the time instructed embassy staff and families to consider taking an ‘early summer vacation.’ He was worried that the situation which they should leave may approach soon.

What might have happened had a US strike on North Korea unleashed a war in Korea in 1994? The commander of the US forces in Korea at the time reported to Bill Clinton that if a second Korean War broke out, it would result in at least one million casualties, $100 billion in costs, and $1 trillion in damage to industry. A total war would have come at great cost to the US and its allies as well.

The crisis was momentarily defused with the signing of the US-DPRK Agreed Framework in October 1994. In that agreement, North Korea accepted the thrust of Washington’s demand, agreeing to close down its existing nuclear facility and accept IAEA inspections – terms that were clearly unfavorable to Pyongyang.

From start to finish, the way Washington handled this episode left little doubt that the US had no intention of leaving East Asia even after the end of the Cold War. It also served to remind the local powers (China, Russia, Japan, South Korea) that the stability of the region depended on the US.

The US never had any intention to implement the Agreed Framework. Although it was agreed on paper that Washington would normalize relations with Pyongyang, stop military threats (nuclear or otherwise), and remove trade and economic barriers, no progress was made on any of these fronts. Neither did the agreement stop the US from repeatedly making new allegations and pushing new demands to North Korea. Aggrandizing North Korea’s ‘threat’ in this way has helped to maintain Japan’s strategic subordination to the United States, through the renewal of the US-Japan alliance that took place in 1996 and 1997.

North Korea came under renewed pressure after George W. Bush took office in 2001. The Neocons who put Bush in the White House sought to transform the distribution of global economic and political power in favor of the United States by exploiting the US’s military advantage. Their hope was to recover the ground they lost in market competition by employing brute force that other imperialist powers did not possess.

US rulers including the Neocons were alarmed by China’s economic rise. They feared an economically ascendant China would eventually amass the military means to challenge the US’s status in East Asia. So the Bush administration came up with measures aimed at China, such as promoting its missile defense system and strengthening alliances in East Asia.

But rather than publically designating China as their enemy, it was much more convenient even for the Bush administration to use North Korea’s ‘threat’ as an excuse to forward-deploy its troops to East Asia, conduct joint military drills with its allies, and strengthen military alliances in the region.

Moreover, a key stated objective of Bush’s ‘War on Terror’ was to prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction by ‘rogue states’, foremost among which was North Korea. The Bush administration, who disliked the Agreed Framework from the beginning, included North Korea in the "axis of evil" alongside Iran and Iraq. In October 2002 Bush accused the North, on dubious grounds, of secretly developing nuclear weapons using highly enriched uranium, finally consigning the Agreed Framework into the dustbin of history.

North Korea protested the tightening of pressure from the US and started reopening its nuclear facilities. Pyongyang now proceeded with its nuclear weapons program in earnest. The North Korean rulers drew a lesson from the US invasion of Iraq and dismantling of Sadam Hussein’s regime in 2003. In June 2003, North Korean officials told a delegation from the US Congress visiting North Korea, ‘We are developing nuclear weapons to avoid the fate of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.’

Soon thereafter, the ‘Six-party Talks’ (featuring the two Koreas, the United States, China, Japan, and Russia) was launched to address the North Korean nuclear program. Hard-pressed to focus on the war in Iraq, Bush wanted to use the talks to buy time while keeping a lid on the North Korean situation. The Bush administration never intended it to be a channel for reaching a negotiated solution. Instead, its pattern was to blackmail North Korea and then react to the latter’s protests by showing up at the negotiating table with conciliatory gestures, dragging its feet as best as it can.

South Korea’s Roh Moo-hyun government (2003–2007) raised much hopes when it proclaimed it would break from the doggedly pro-US diplomacy of the traditional right. However, as soon as the North Korean nuclear question erupted, Roh took pains to cooperate with Bush in pressuring North Korea. Roh also sent the largest military contingent to Iraq after the US and Britain, saying he would in return secure Bush’s cooperation in the peaceful resolution of the North Korean nuclear question. Strange phrases like ‘pro-American self-reliance’ were concocted to legitimize this move. Many were deeply disillusioned by Roh’s betrayal.

When the Bush administration imposed new financial sanctions on the North, the North Korean representative for the Six-Party Talks expressed Pyongyang’s outrage thus: ‘Finance is like blood. Once it stops flowing, the heart stops.’ North Korea in turn took advantage of the US’ entanglement in Iraq to raise the stakes of the game. In 2006, North Korea conducted its first nuclear test. The imperialist pressures of the Bush administration had produced a blowback in the form of a true weapon of mass destruction. And there was not much Bush could do about it, other than scream at North Korea: the US was simply too consumed by Iraq. Contrary to the Neocon’s initial ambitions that motivated the ‘Axis of Evil’ talk, American power was revealing its limits. This also implied a weakened US grip over East Asia.

The US had made several attempts, including the war in Iraq, to reverse the decline in its relative position. These proved unsuccessful. The global economic crisis that originated from the US in 2008 further eroded its hegemony. In the meantime, ‘the rise of the Rest’ was becoming more evident. The rise of China was especially stark. China quickly recovered from the economic crisis and pulled other countries along with it. US allies in Asia, including South Korea and Japan, were becoming more and more economically integrated with China. In short, China emerged as a major challenger to US hegemony in the Asia-Pacific region and potentially on the global stage.

Obama, who became US President in 2008, saw China’s economic and political rise as a threat that required a serious response. Hence his decision to shift US resources to the Asia-Pacific region. Hence the term ‘Pivot to Asia’.

Figure 3 |

The Obama administration has made a rash of military efforts to maintain supremacy in East Asia in response to China’s arms buildup. It sought to bolster its military alliances with Japan, South Korea and Australia, and to build new ones with Vietnam, Singapore and India, with a view to encircling China. (See Figure 3)

China’s rise and Washington’s strategy to contain it has been at the root of the increasing geopolitical instability in East Asia, to which the instability in the Korean peninsula was closely linked.

The US, in proclaiming its ‘Pivot to Asia’, sought to make South Korea a pillar in its strategy of encircling China. It wanted to build a triangular alliance comprising Japan, South Korea and the US by pushing for military cooperation between Korea and Japan. The key agenda behind the initiative was to build trilateral cooperation around the US missile defense system.

The Obama administration was no different to its predecessors when it came to exaggerating North Korea’s ‘threat’ and twisting the latter’s arm to serve its own strategic interests. Washington has consistently invoked the North Korean ‘threat’ as the primary justification for strengthening alliances in the region, promoting US-Japan-South Korea military cooperation (including on missile defense), etc.

The way Obama used North Korea in this manner was clearly illustrated by two incidents, the sinking of a South Korean warship in 2010 and the artillery battle between North and South in Yeonpyeong the same year. When the South Korean naval ship Cheonan suddenly sank in the Yellow Sea – the cause is still unclear – the right wing government of Lee Myung-bak and the Obama administration rushed to conclude that it was the work of Pyongyang.

Obama then used the incident to compel Japan’s Hatoyama government to scrap its plan to move the US Air Force base out of Okinawa, the argument being that Japan was also exposed to a North Korean attack.

In addition, the US impressed (yet again) upon South Korea the need for its military alliance with US and continued joint military exercises around the Korean Peninsula. This led to increased tensions and in November 2010 a mutual shelling took place between artillery units of the two Koreas in Yeonpyeong island near the border. (See Figure 1) The next day, the US brought an aircraft carrier into the Yellow Sea against China’s protest.

Such behavior has raised questions in South Korea about whether Washington really had any desire to solve the problem of North Korean nukes and mitigate tensions. Obama characterized its North Korea policy as ‘strategic patience’ and took no steps to improve relations with Pyongyang. Rather, North Korea was told to give up nuclear weapons as a precondition for dialogue. It goes without saying that the South Korean right wing governments of Lee Myung-bak (2008–2013) and Park Geun-hye (2013–2017) actively collaborated in the policy of ‘strategic patience’.

It was hard for Pyongyang to interpret Obama’s policy as anything but hostile. In 2009, when the US tightened economic sanctions against North Korea for launching satellites, North Korea responded by building a uranium enrichment facility.

Washington and Seoul brought pressure to bear on Pyongyang with the combined weight of cashflow-choking economic sanctions and increased US-South Korean military might, with greater intensity each time North Korea fired a missile or conducted a nuclear test. InterKorean economic exchanges ground to a near-complete halt. Since 2010, the scale of joint military drills grew noticeably each year, and major US strategic assets were openly deployed to Korea. Public displays of US strategic bombers flying into the area, as well as ‘decapitation’ strike exercises targeting the North Korean leadership, were more than enough to send chills down North Korea’s spine and to provoke China.

South Korea’s participation in missile defense played an especially prominent role in turning up the heat on North Korea. South Korea had been hesitant about participating in MD out of fear of arousing China’s ire, but its attitude gradually shifted as North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities developed. Finally, in 2016, Park agreed to the deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system, a key component of MD, to Korea in the face of Beijing’s seething outrage. The deployment of THAAD in Korea was a necessary step for the US to intercept Chinese missiles in the event of war. It was a demand Washington had pressed Seoul with for a long time, and now its wish was finally fulfilled.

During Obama’s eight year term, dialogue between Washington and Pyongyang never went beyond the level of informal contact. Over the same period, North Korea sped up its nuclear program and conducted four nuclear tests.

At the beginning I pointed out that instability in the Korean Peninsula must be examined in the context of the imperialist world system. Over the past 25 years, the US has had many opportunities to resolve the issue of North Korean nuclear weapons. However, the US has always approached the issue in connection to its goal of maintaining and strengthening its power and influence in East Asia. This has been an approach shared by other imperialist powers including China, Russia and Japan.

North Korea has been playing a game of survival by resorting to brinkmanship tactics in response to US threats. Kim Jong-eun and North Korean officials are trying to increase their chances of survival against the conventional weaponry and military exercises of the US and South Korea, flaunting their ability to retaliate with nukes if push comes to shove. The nuclear warheads and missiles also serve as a means of dragging the US to the negotiating table. North Korea’s official media and diplomats often hurl insults to the US, but Pyongyang has continued to seek dialogue through other channels. The paramount objective for the North Korean nationalist regime is to secure its own stable place within the system of capitalist states.

Faced with pressure from the imperialist world system, North Korean rulers chose to develop nuclear weapons. The North Korean Party paper Rohdong claimed: ‘Peace and stability in the peninsula, East Asia, and moreover the wider world is ensured by virtue of our being a nuclear power.’ Nuclear weapons, however, are not an effective means of resisting imperialism; they do not keep Pyongyang’s rulers from having to constantly face imperialist rulers who wish to see the North Korean regime collapse.

Moreover, there’s the problem of Trump. There are certainly quite a few Wall Street bankers and retired generals in the Trump administration, but there are also features that clearly set it apart from past Republican governments. Trump’s supporters include those who, like Steve Bannon, identify with European right-wing populism, which indicates the extent to which Trump’s rise to power is connected with the international wave of right-wing populism.

Trump came to power in a context where the free market-oriented post-war international order the US had built was beginning to crack, while mainstream US politicians were failing to articulate a way to preserve US imperial hegemony under these circumstances. The solution proposed by Trump was a shift in the direction of US strategy, encapsulated in the slogan ‘America first’. This shift has had destabilizing effects throughout the world and in East Asia and the Korean peninsula in particular. It was Obama’s strategy to maintain US hegemony by redirecting resources to East Asia, in particular to contain China. In practice, however, Obama had to deal with challenges arising from Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Asia at the same time, and so the gap between his administration’s foreign policy rhetoric and fiscal and military realities on the ground widened over time. Obama thus ultimately failed to halt the further erosion of US power relative to rival countries.

Trump criticized the Obama administration’s foreign policy and insisted that he had a solution. On the other hand, he had previously criticized the US wars in the Middle East post 9/11, and said that he was willing to talk with North Korea. This had led some liberals in South Korea to harbor the illusion that Trump would be better than Clinton for bringing peace in the Korean peninsula.

But once elected, Trump faulted his predecessor for being too weak, and flaunted his bravado as commander-in-chief by engaging in military actions. He pounded Syria with Tomahawk missiles in April, dropped the most devastating non-nuclear bomb in Afghanistan, and recently decided to send more troops there. He embarrassed even his own generals when he said the US nuclear stockpile could be increased tenfold – such is his eagerness to increase arms spending. At around the same time as the bombs hit Syria and Afghanistan, Trump began to stir up tensions in the Korean peninsula by sending in an aircraft carrier.

The Korean Peninsula is now facing the most dangerous situation it has seen in the 21st century. Trump’s words have greatly contributed to this. Talk of ‘fire and fury’ to befall North Korea was just one among numerous threats to come out of Trump’s mouth and Twitter account.

In this regard, Trump’s speech to the UN in September is significant: it starkly revealed the meaning of his ‘America First’ policy, and brought his North Korea-bashing rhetoric to an apogee.

Trump used the words ‘sovereignty’ and ‘sovereign’ 21 times in the UN speech. He said:

In foreign affairs, we are renewing this founding principle of sovereignty ... As President of the United States, I will always put America first, just like you, as the leaders of your countries will always, and should always, put your countries first.

By repeatedly emphasizing sovereignty Trump was making clear that US interests came first; that the US would respond very firmly to challenges coming from any state or other entity, ‘from the Ukraine to the South China Sea’. He also showed that he was ready to ignore or overturn the existing neoliberal international order if necessary.

Trump berated the ‘rogue regimes’ of Iran and Venezuela in his UN speech, but the ‘rogue regime’ for which he reserved the most venom was North Korea. He warned the latter:

The United States has great strength and patience, but if it is forced to defend itself or its allies, we will have no choice but to totally destroy North Korea. Rocket Man is on a suicide mission for himself and for his regime.

Trump’s message here is qualitatively different from those of his predecessors. Neither Obama nor even George W. Bush went so far as to threaten North Korea with total annihilation. They certainly did threaten the regime, but nevertheless made a distinction between the regime and the North Korean people, in however hypocritical a way. For Trump, such distinction seems meaningless.

The difference cannot simply be reduced to Trump’s idiosyncratic style of speech. Key figures in Trump’s administration such as Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley, Defense Secretary James Mattis, and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson continue to emphasize the availability of military options.

On September 23 after Trump’s UN speech, US Air Force B-1B Lancer bombers from Guam flew in international airspace over waters east of North Korea. According to the US Department of Defense, ‘This is the farthest north of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) any US fighter or bomber aircraft have flown North Korea’s coast in the 21st century.’ The Pentagon’s Chief Spokesperson Dana W. White explained the meaning of this operation: ‘This mission is a demonstration of US resolve and a clear message that the President has many military options to defeat any threat.’ On September 25, North Korean Foreign Minister Lee Yong-ho said this amounted to ‘a declaration of war on North Korea.’

It is unclear whether Trump has made up his mind to risk a full-scale war against North Korea. Trump’s generals including ‘Mad Dog’ Mattis are well aware of the likely consequences. A pre-emptive attack by the US will immediately push all sides toward an all-out war. An all-out war in the Korean Peninsula, even a conventional one, will involve a melee of two million soldiers from the North, South and the US raging through the land. Two million is a lower-bound projection assuming China stays out of the mess. Pyongyang and Seoul are only 200 km apart: conventional war in between the two capitals alone would sacrifice millions of civilians.

In the worst case, a nuclear war could break out. In such a war, Washington would most likely win by obliterating the North with conventional and/or nuclear weapons, but probably after Seoul and Tokyo have been laid to waste. More than 25 million people live in Seoul and the greater metropolitan area. A nuclear bomb destroying Seoul is not only horrific to imagine, it would also be a painful loss to Washington.

The sheer scale of damage that a second Korean War is likely to bring works to constrain the behavior of both parties to some extent. However, it would be hasty to therefore preclude the possibility of a war in the peninsula.

For the Trump administration, the possibility of a nuclear armed North Korea precipitating nuclear proliferation and thereby threatening the US’ global nuclear supremacy is a worrying prospect. Therefore a challenge for Trump is to demonstrate to other capitalist powers that Washington has the situation under control while maintaining America’s nuclear advantage.

It follows that Trump is likely to keep applying "maximum pressure" to Pyongyang. In a meeting with his top military brass on October 6, Trump called the moment ‘the calm before the storm.’ Trump is likely to ramp up military pressure alongside economic sanctions. Having already sent B-1B bomber into North Korean sea, he could decide to send in an aircraft carrier next time. In fact, US aircraft carrier had previously sailed to the eastern coast of North Korea after the USS Pueblo incident in 1968. The US plans to increase deployment of its strategic weapons to Korea, which is certain to provoke Pyonyang.

If Trump continues on this path of escalating tensions, North Korean rulers will likely respond with yet more nuclear tests or missile launches. The vicious cycle of escalations may very well spark accidental military clashes.

Another factor that casts an ominous shadow on the Korean situation is the intensifying rivalry among imperialist countries surrounding the peninsula, especially the US and China. Trump and his key aides believe that chastising China economically is inseparable from the task of preventing China’s rise as a political and military powerhouse.

On October 18, Secretary of State Tillerson sent a warning to China in a speech at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS): ‘We will not shrink from China’s challenges to the rule-based order and where the Chinese subverts the sovereignty of neighboring countries and disadvantages in the US and our friends.’

He stressed that it was vital to defend US interests in the Indo-Pacific region, home to the most vibrant economic growth in the world and to major maritime transportation routes; to that end, Tillerson continued, Washington would strengthen cooperation with countries such as India, Japan and Australia.

While trying to curtail Chinese expansion from the South by strengthening ties with India and Japan (such as the joint military exercise between the 3 states on the Indian Ocean), the Trump administration is following its predecessors in urging Japan and South Korea to enhance trilateral cooperation with the US to contain China from the East. As always, North Korea is cited as the excuse for this initiative.

Trump has been calling on China to strengthen economic sanctions against North Korea, accompanied by the threat of sanctions against Chinese enterprises and individuals.

Over the years, North Korea has responded to tightening sanctions from the West by seeking alternative sources of foreign exchange and by trying to revive the economy. One result is that trade with China as a share of North Korean GDP has surged over the last 20 years, to the extent that the economy has now become absolutely dependent on China.

However, the close trading relation can also create subtle tensions between Beijing and Pyongyang. Kim Jong-eun’s regime is not happy about the adverse terms of trade imposed by China upon North Korea. Above all, it is concerned that China’s growing economic clout will translate into greater political influence on Pyongyang, so that North Korea will be treated as the ‘Fourth Province’ of China’s northeastern region. North Korea’s recent moves to develop trade relations with Russia are part of its effort to escape excessive reliance on the Chinese economy. The mysterious murder in Malaysia this year of Kim Jong-eun’s half-brother Kim Jong-nam, who was under Beijing’s protection, as well as the 2013 execution of Kim Jong-eun’s uncle Jang Sung-taek, who’s had friendly relations with Chinese leaders, reveal the nature of Pyongyang’s relationship with Beijing. One of Jang Sung-taek’s crimes cited by the regime was that he had sold coal, land and other resources on the cheap to a ‘foreign country’ – an act of ‘treason’. The identity of that ‘foreign country’ wasn’t difficult to infer.

China, for its part, finds Kim Jong-eun’s regime with its penchant for nuclear tests to be a headache, not least because North Korean ‘provocations’ offer the US the perfect excuse to enlist South Korea and Japan in its effort to encircle China, and also because North Korean nukes could set off a nuclear domino effect rippling through South Korea and Japan.

Nonetheless, China does not want the collapse of the North Korean regime. Thus Beijing is only partially implementing Trump’s demands for tightened sanctions. If the North Korean regime collapses, China could face a flood of refugees pouring into China across the North Korean border. Also, if North Korea gets absorbed to the South, China will have to share a border for the first time ever with a pro-Western country that hosts over 28,000 US troops on its soil – within arm’s reach from Beijing.

Thus China’s state-run newspaper Global Times proclaimed in an editorial in August that, ‘If the US and South Korea carry out strikes and try to overthrow the North Korean regime and change the political pattern of the Korean Peninsula, China will prevent them from doing so.’

As an imperialist power itself, Russia has different interests from those of China, but shares China’s unwillingness to see the North Korean regime collapse. Russia, too, is disturbed by Washington’s moves to establish missile defense in East Asia under the pretext of North Korea.

The Korean peninsula is thus tangled up in inter-imperialist conflict: not in the vicinity or periphery but smack in the middle of it. Such entanglement can amplify tensions in the peninsula when coupled with specific events in the wider region in the not-so-distant future; in the worst case, it may lead to another imperialist proxy war.

As tensions continued to rise, many in South Korea hoped the government that came to power on the back of mass protests that brought down the rightwing government in early 2017 would work to de-escalate the situation.

But the current South Korean President Moon Jae-in is betraying the hopes of the people who supported him. He chose to remain loyal to the alliance with the US, to cooperate with Trump on pressuring North Korea and strengthening sanctions. Moon also rushed to cooperate on missile defense, giving his nod to the deployment of THAAD. Improving inter-Korean relations has been put off until the issue of North Korean nuclear weapons has been resolved. At the US-South Korea summit meeting of June 30, Moon and Trump declared that ‘the door to dialogue with the DPRK remains open under the right circumstances.’ The conditional phrase, ‘under the right circumstances,’ implies that Moon is willing to pursue dialogue with Pyongyang only under circumstances which US finds favorable. Moon also must have been the only leader in the developed world to publicly praise Trump’s September UN speech. Moon is also stepping up military cooperation with the US, receiving support from state-of-the-art US military assets and agreeing to purchase high-tech US weaponry. His pro-American leanings have begun to create subtle cracks among his base of support. These cracks may widen in the future.

So far, we have seen how imperialism has created and deepened instability in the Korean peninsula, with a focus on the North Korean nuclear program. In particular, we have noted the ominous developments under the Trump presidency.

It is of course difficult to say how likely a war is to erupt in Korea, either in the present or the future. As in 1994, a war could be fortuitously averted.

However, we cannot continue to hope for such good fortune while living in constant fear of nuclear warfare. On September 15, when North Korea flew a rocket over Japan, a US warship patrolling the waters near the Korean peninsula was reported to have ‘received a warning order, or WARNO, to be prepared to fire Tomahawk missiles at North Korean targets,’ a chilling reminder that luck is not to be relied upon. The fact that Japan’s right-wing Abe government, having won the election by agitating against the North Korean ‘threat’, is preparing to amend the peace constitution and transform Japan into a war-capable country, is yet another cause for concern. These signs clearly point to a dangerous path ahead for the Korean peninsula.

But there are other signs that point to an alternative path. South Korea is home to a massive working class who has experience in building resistance. The South Korean movement has a history of opposing US imperialism through mobilizations against the Iraq war, the deployment of Korean troops to Iraq, and the expansion of US bases within South Korea. Mass protests have recently brought down a corrupt-to-the-bone daughter of a dictator from power.

The South Korean left must begin the work of building a mass movement for peace in the Korean peninsula. This will involve many twists and turns, but revolutionary Marxists will have much to contribute to that process. Ultimately, we must aim to unleash the potential of the working class to overthrow the capitalist system that is at the root of this instability. In the pursuit of this task, revolutionaries in Korea would do well to bear in mind the dictum by the Irish revolutionary James Connolly: ‘The only true prophets are those who carve out the future which they announce.’

IMR Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 30 December 2021