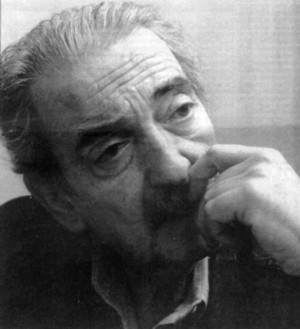

among other things/defeat

is the source of all humbleness/confirms

the humbleness of the compañeros who

died for the people/loving them

– Juan Gelman (tr. Joan Lindgren)

A child of the many currents that passed through the Latin American Left in the 1960s and ’70s, Argentina’s Montoneros also suffered the same sad and grisly fate of almost all of the armed movements of the period.

The main sources of its ideology were liberation theology and the left-wing Peronism of the ‘descamisados,’ the shirtless who were Eva Peron’s base of support. Juan Peron’s removal from power in 1955 and subsequent exile did nothing to kill the movement he led, and in his absence from the homeland Peronism became a protean movement, taking on forms from all ends of the political spectrum. The Montoneros – who adopted the name of the followers of 19th century of caudillos from the interior of the country – described their doctrine as Christian, national, and socialist, and as time passed the socialist element almost totally eclipsed the Christian, as the group entered into alliances with the leftist Fuerezas Armadas Revolucionarias (FAR, Armed Revolutionary Forces) and the Trotskyist Ejercito Revolucionario del Pueblo (ERP, People’s Revolutionary Army).

In their early days their primary demand was for the return of Peron to both Argentina and power (Peron Vuelve!) and an end to the illegitimate governments that had succeeded him. The Montonero’s entry onto the Argentine political scene was signaled in striking fashion, with the June 1, 1970 kidnapping and execution of the former president of Argentina General Pedro Aramburu. Their almost Christ-like veneration of the Perons was one of the motive forces for the kidnapping and killing of the General. In their communiqué announcing the kidnapping they enumerated the charges against Aramburu, which included “the public defamation of the names of the legitimate popular leaders in general and especially of our leader Juan Domingo Peron,” as well as “the profanation of the place where the remains of Compañera Evita were resting and the later disappearance of same, taking from the people even the final material remains of she who was their standard bearer.” Such loyalty could not but please Peron, who saw the Montoneros and their violence as a key element in his strategy for return to power.

In the period before Peron’s return the Montoneros paid the price of their armed struggle: members of the group were among the 16 Leftists murdered after a failed escape at the Rawson prison camp near Trelew in September 1972, a cold-blooded precursor of much that was to occur a few years later in the Dirty War.

Peron’s acceptance of the Montoneros, whose members occupied electoral offices throughout the country and who were especially close to Hector Campora – Peron’s stand in for Peron in the elections of 1973 – didn’t survive Peron’s actual return to Argentina after his party’s victory in the same elections. In fact, things were to take an evil turn the very day of that return, June 20, 1973, when at Ezeiza, near the Buenos Aires airport, right-wing Peronists fired on the Montoneros. The resulting death toll, which was never definitively settled upon, was somewhere between two dozen and two hundred.

The war continued as the Montoneros executed union leader Jose Rucci, and Peron moved ever more to the Right, while the extreme Right of the Peronist movement, most brutally in the form of Jose Lopez Rega and the killers of the Argentine Anti-Communist Movement, were given increasing power by Peron and later by his wife Isabel when she assumed the presidency.

The final rupture occurred in public fashion on May 1, 1974. During the leader’s speech the Montoneros, whose supporters filled the Plaza de Mayo, chanted slogans against the “gorillas” surrounding Peron. Peron interrupted his discourse to call the leftists “stupid,” at which point the Left left the rally and the Montoneros became an underground movement.

The group was able to procure massive amounts of funds in September 1974 when they kidnapped the Born brothers, the main stockholders of one of Argentina’s largest grain exporters. There is still controversy and questions about the ultimate fate of the $17,000,000 ransom they received for the return of the brothers.

There then followed the disintegration of the Argentine economy and political system; the military assumed power in 1976 and the Dirty War began. Though tracked by the authorities and tortured and disappeared, isolated from the masses, the Montoneros were still able to carry out major actions, like the bombing of the headquarters of the security police in Buenos Aires in September, 1976, an act which caused 18 deaths. It was only in December 2007 that a Buenos Aires court decided that the act did not constitute a crime against humanity.

Internal discord became the rule within the Montoneros, as members of the organization, like the poet Juan Gelman, questioned the emphasis on armed action and the separation from mass and union activity. Shortly after Gelman’s public departure from the organization in 1979 it ceased to exist as an active force. Yet the dissension continued, and sectors of the leadership, particularly the principal leader Mario Firmenich, were later accused by militants of having been police agents.

The armed Montoneros never exceeded 7,000 members, but the group figures prominently among the 30,000 disappeared of the period.