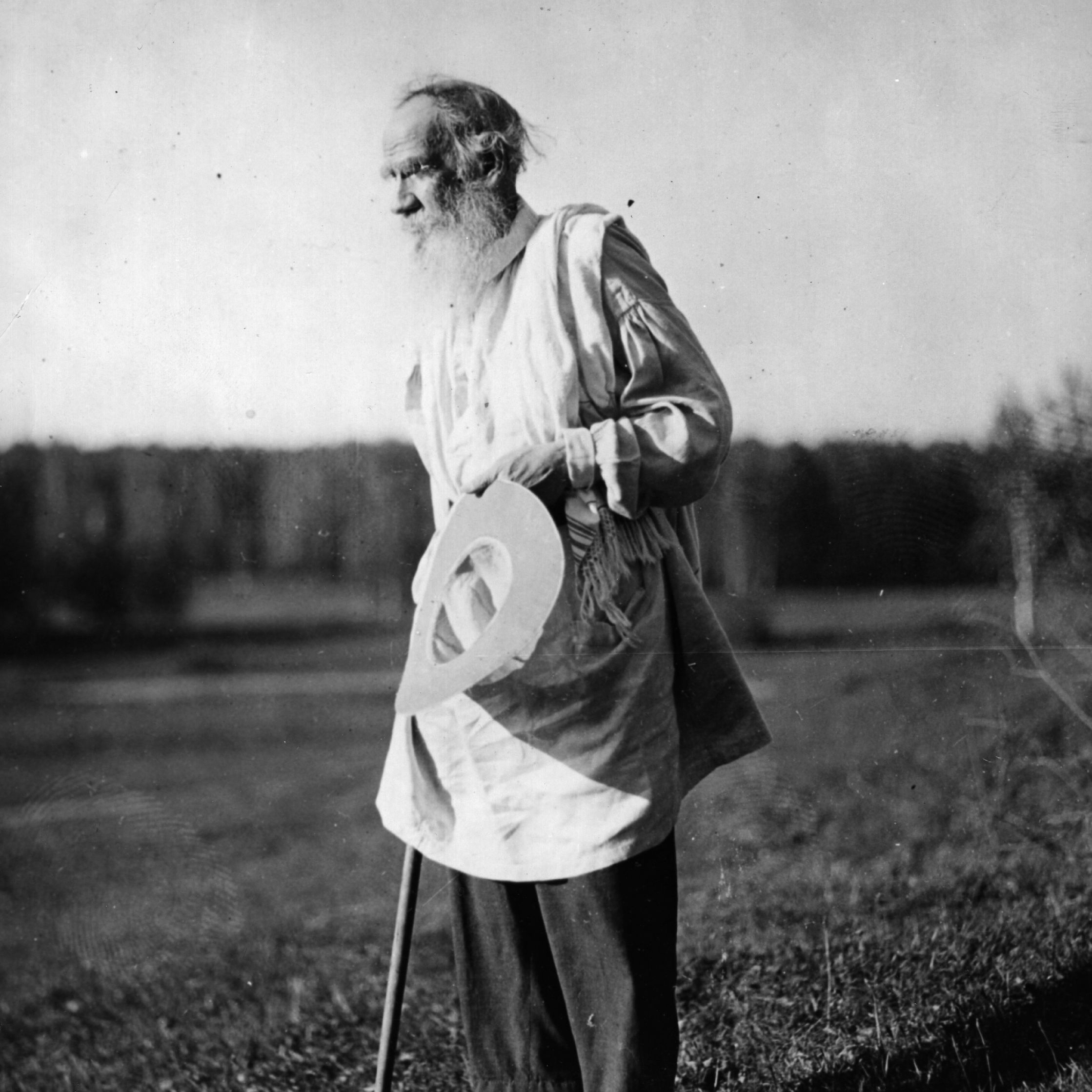

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1912

Source: The Forged Coupon: And Other Stories, by Leo Tolstoy, 1912, Translated from the Russian by Herman Bernstein, published by Ogilvie Publishing Company, 57 Rose Street, New York, produced for Gutenberg.org by Judith Boss and David Widger, 2006.

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

Peter Nikolaevich Szentizky's views of the peasantry had now changed for the worse, and the peasants had an equally bad opinion of him. In the course of a single year they felled twenty-seven oaks in his forest, and burnt a barn which had not been insured. Peter Nikolaevich came to the conclusion that there was no getting on with the people around him.

At that very time the landowner, Liventsov, was trying to find a manager for his estate, and the Marshal of the Nobility recommended Peter Nikolaevich as the ablest man in the district in the management of land. The estate owned by Liventsov was an extremely large one, but there was no revenue to be got out of it, as the peasants appropriated all its wealth to their own profit. Peter Nikolaevich undertook to bring everything into order; rented out his own land to somebody else; and settled with his wife on the Liventsov estate, in a distant province on the river Volga.

Peter Nikolaevich was always fond of order, and wanted things to be regulated by law; and now he felt less able of allowing those raw and rude peasants to take possession, quite illegally too, of property that did not belong to them. He was glad of the opportunity of giving them a good lesson, and set seriously to work at once. One peasant was sent to prison for stealing wood; to another he gave a thrashing for not having made way for him on the road with his cart, and for not having lifted his cap to salute him. As to the pasture ground which was a subject of dispute, and was considered by the peasants as their property, Peter Nikolaevich informed the peasants that any of their cattle grazing on it would be driven away by him.

The spring came and the peasants, just as they had done in previous years, drove their cattle on to the meadows belonging to the landowner. Peter Nikolaevich called some of the men working on the estate and ordered them to drive the cattle into his yard. The peasants were working in the fields, and, disregarding the screaming of the women, Peter Nikolaevich’s men succeeded in driving in the cattle. When they came home the peasants went in a crowd to the cattle-yard on the estate, and asked for their cattle. Peter Nikolaevich came out to talk to them with a gun slung on his shoulder; he had just returned from a ride of inspection. He told them that he would not let them have their cattle unless they paid a fine of fifty kopecks for each of the horned cattle, and twenty kopecks for each sheep. The peasants loudly declared that the pasture ground was their property, because their fathers and grandfathers had used it, and protested that he had no right whatever to lay hand on their cattle.

“Give back our cattle, or you will regret it,” said an old man coming up to Peter Nikolaevich.

“How shall I regret it?” cried Peter Nikolaevich, turning pale, and coming close to the old man.

“Give them back, you villain, and don’t provoke us.”

“What?” cried Peter Nikolaevich, and slapped the old man in the face.

“You dare to strike me? Come along, you fellows, let us take back our cattle by force.”

The crowd drew close to him. Peter Nikolaevich tried to push his way, through them, but the peasants resisted him. Again he tried force.

His gun, accidentally discharged in the melee, killed one of the peasants. Instantly the fight began. Peter Nikolaevich was trodden down, and five minutes later his mutilated body was dragged into the ravine.

The murderers were tried by martial law, and two of them sentenced to the gallows.