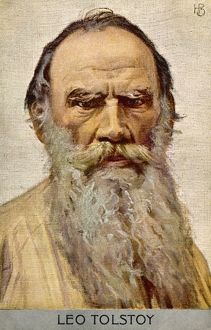

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1869

Source: Original Text from Gutenberg.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

Before the beginning of the campaign, Rostóv had received a letter from his parents in which they told him briefly of Natásha’s illness and the breaking off of her engagement to Prince Andrew (which they explained by Natásha’s having rejected him) and again asked Nicholas to retire from the army and return home. On receiving this letter, Nicholas did not even make any attempt to get leave of absence or to retire from the army, but wrote to his parents that he was sorry Natásha was ill and her engagement broken off, and that he would do all he could to meet their wishes. To Sónya he wrote separately.

“Adored friend of my soul!” he wrote. “Nothing but honor could keep me from returning to the country. But now, at the commencement of the campaign, I should feel dishonored, not only in my comrades’ eyes but in my own, if I preferred my own happiness to my love and duty to the Fatherland. But this shall be our last separation. Believe me, directly the war is over, if I am still alive and still loved by you, I will throw up everything and fly to you, to press you forever to my ardent breast.”

It was, in fact, only the commencement of the campaign that prevented Rostóv from returning home as he had promised and marrying Sónya. The autumn in Otrádnoe with the hunting, and the winter with the Christmas holidays and Sónya’s love, had opened out to him a vista of tranquil rural joys and peace such as he had never known before, and which now allured him. “A splendid wife, children, a good pack of hounds, a dozen leashes of smart borzois, agriculture, neighbors, service by election...” thought he. But now the campaign was beginning, and he had to remain with his regiment. And since it had to be so, Nicholas Rostóv, as was natural to him, felt contented with the life he led in the regiment and was able to find pleasure in that life.

On his return from his furlough Nicholas, having been joyfully welcomed by his comrades, was sent to obtain remounts and brought back from the Ukraine excellent horses which pleased him and earned him commendation from his commanders. During his absence he had been promoted captain, and when the regiment was put on war footing with an increase in numbers, he was again allotted his old squadron.

The campaign began, the regiment was moved into Poland on double pay, new officers arrived, new men and horses, and above all everybody was infected with the merrily excited mood that goes with the commencement of a war, and Rostóv, conscious of his advantageous position in the regiment, devoted himself entirely to the pleasures and interests of military service, though he knew that sooner or later he would have to relinquish them.

The troops retired from Vílna for various complicated reasons of state, political and strategic. Each step of the retreat was accompanied by a complicated interplay of interests, arguments, and passions at headquarters. For the Pávlograd hussars, however, the whole of this retreat during the finest period of summer and with sufficient supplies was a very simple and agreeable business.

It was only at headquarters that there was depression, uneasiness, and intriguing; in the body of the army they did not ask themselves where they were going or why. If they regretted having to retreat, it was only because they had to leave billets they had grown accustomed to, or some pretty young Polish lady. If the thought that things looked bad chanced to enter anyone’s head, he tried to be as cheerful as befits a good soldier and not to think of the general trend of affairs, but only of the task nearest to hand. First they camped gaily before Vílna, making acquaintance with the Polish landowners, preparing for reviews and being reviewed by the Emperor and other high commanders. Then came an order to retreat to Sventsyáni and destroy any provisions they could not carry away with them. Sventsyáni was remembered by the hussars only as the drunken camp, a name the whole army gave to their encampment there, and because many complaints were made against the troops, who, taking advantage of the order to collect provisions, took also horses, carriages, and carpets from the Polish proprietors. Rostóv remembered Sventsyáni, because on the first day of their arrival at that small town he changed his sergeant major and was unable to manage all the drunken men of his squadron who, unknown to him, had appropriated five barrels of old beer. From Sventsyáni they retired farther and farther to Drissa, and thence again beyond Drissa, drawing near to the frontier of Russia proper.

On the thirteenth of July the Pávlograds took part in a serious action for the first time.

On the twelfth of July, on the eve of that action, there was a heavy storm of rain and hail. In general, the summer of 1812 was remarkable for its storms.

The two Pávlograd squadrons were bivouacking on a field of rye, which was already in ear but had been completely trodden down by cattle and horses. The rain was descending in torrents, and Rostóv, with a young officer named Ilyín, his protégé, was sitting in a hastily constructed shelter. An officer of their regiment, with long mustaches extending onto his cheeks, who after riding to the staff had been overtaken by the rain, entered Rostóv’s shelter.

“I have come from the staff, Count. Have you heard of Raévski’s exploit?”

And the officer gave them details of the Saltánov battle, which he had heard at the staff.

Rostóv, smoking his pipe and turning his head about as the water trickled down his neck, listened inattentively, with an occasional glance at Ilyín, who was pressing close to him. This officer, a lad of sixteen who had recently joined the regiment, was now in the same relation to Nicholas that Nicholas had been to Denísov seven years before. Ilyín tried to imitate Rostóv in everything and adored him as a girl might have done.

Zdrzhinski, the officer with the long mustache, spoke grandiloquently of the Saltánov dam being “a Russian Thermopylae,” and of how a deed worthy of antiquity had been performed by General Raévski. He recounted how Raévski had led his two sons onto the dam under terrific fire and had charged with them beside him. Rostóv heard the story and not only said nothing to encourage Zdrzhinski’s enthusiasm but, on the contrary, looked like a man ashamed of what he was hearing, though with no intention of contradicting it. Since the campaigns of Austerlitz and of 1807 Rostóv knew by experience that men always lie when describing military exploits, as he himself had done when recounting them; besides that, he had experience enough to know that nothing happens in war at all as we can imagine or relate it. And so he did not like Zdrzhinski’s tale, nor did he like Zdrzhinski himself who, with his mustaches extending over his cheeks, bent low over the face of his hearer, as was his habit, and crowded Rostóv in the narrow chanty. Rostóv looked at him in silence. “In the first place, there must have been such a confusion and crowding on the dam that was being attacked that if Raévski did lead his sons there, it could have had no effect except perhaps on some dozen men nearest to him,” thought he, “the rest could not have seen how or with whom Raévski came onto the dam. And even those who did see it would not have been much stimulated by it, for what had they to do with Raévski’s tender paternal feelings when their own skins were in danger? And besides, the fate of the Fatherland did not depend on whether they took the Saltánov dam or not, as we are told was the case at Thermopylae. So why should he have made such a sacrifice? And why expose his own children in the battle? I would not have taken my brother Pétya there, or even Ilyín, who’s a stranger to me but a nice lad, but would have tried to put them somewhere under cover,” Nicholas continued to think, as he listened to Zdrzhinski. But he did not express his thoughts, for in such matters, too, he had gained experience. He knew that this tale redounded to the glory of our arms and so one had to pretend not to doubt it. And he acted accordingly.

“I can’t stand this any more,” said Ilyín, noticing that Rostóv did not relish Zdrzhinski’s conversation. “My stockings and shirt... and the water is running on my seat! I’ll go and look for shelter. The rain seems less heavy.”

Ilyín went out and Zdrzhinski rode away.

Five minutes later Ilyín, splashing through the mud, came running back to the chanty.

“Hurrah! Rostóv, come quick! I’ve found it! About two hundred yards away there’s a tavern where ours have already gathered. We can at least get dry there, and Mary Hendríkhovna’s there.”

Mary Hendríkhovna was the wife of the regimental doctor, a pretty young German woman he had married in Poland. The doctor, whether from lack of means or because he did not like to part from his young wife in the early days of their marriage, took her about with him wherever the hussar regiment went and his jealousy had become a standing joke among the hussar officers.

Rostóv threw his cloak over his shoulders, shouted to Lavrúshka to follow with the things, and—now slipping in the mud, now splashing right through it—set off with Ilyín in the lessening rain and the darkness that was occasionally rent by distant lightning.

“Rostóv, where are you?”

“Here. What lightning!” they called to one another.