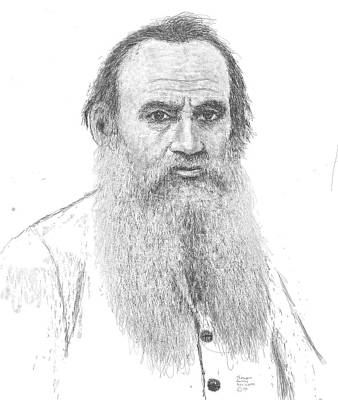

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1869

Source: Original Text from Gutenberg.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

Pierre drove to Márya Dmítrievna’s to tell her of the fulfillment of her wish that Kurágin should be banished from Moscow. The whole house was in a state of alarm and commotion. Natásha was very ill, having, as Márya Dmítrievna told him in secret, poisoned herself the night after she had been told that Anatole was married, with some arsenic she had stealthily procured. After swallowing a little she had been so frightened that she woke Sónya and told her what she had done. The necessary antidotes had been administered in time and she was now out of danger, though still so weak that it was out of the question to move her to the country, and so the countess had been sent for. Pierre saw the distracted count, and Sónya, who had a tear-stained face, but he could not see Natásha.

Pierre dined at the club that day and heard on all sides gossip about the attempted abduction of Rostóva. He resolutely denied these rumors, assuring everyone that nothing had happened except that his brother-in-law had proposed to her and been refused. It seemed to Pierre that it was his duty to conceal the whole affair and reestablish Natásha’s reputation.

He was awaiting Prince Andrew’s return with dread and went every day to the old prince’s for news of him.

Old Prince Bolkónski heard all the rumors current in the town from Mademoiselle Bourienne and had read the note to Princess Mary in which Natásha had broken off her engagement. He seemed in better spirits than usual and awaited his son with great impatience.

Some days after Anatole’s departure Pierre received a note from Prince Andrew, informing him of his arrival and asking him to come to see him.

As soon as he reached Moscow, Prince Andrew had received from his father Natásha’s note to Princess Mary breaking off her engagement (Mademoiselle Bourienne had purloined it from Princess Mary and given it to the old prince), and he heard from him the story of Natásha’s elopement, with additions.

Prince Andrew had arrived in the evening and Pierre came to see him next morning. Pierre expected to find Prince Andrew in almost the same state as Natásha and was therefore surprised on entering the drawing room to hear him in the study talking in a loud animated voice about some intrigue going on in Petersburg. The old prince’s voice and another now and then interrupted him. Princess Mary came out to meet Pierre. She sighed, looking toward the door of the room where Prince Andrew was, evidently intending to express her sympathy with his sorrow, but Pierre saw by her face that she was glad both at what had happened and at the way her brother had taken the news of Natásha’s faithlessness.

“He says he expected it,” she remarked. “I know his pride will not let him express his feelings, but still he has taken it better, far better, than I expected. Evidently it had to be....”

“But is it possible that all is really ended?” asked Pierre.

Princess Mary looked at him with astonishment. She did not understand how he could ask such a question. Pierre went into the study. Prince Andrew, greatly changed and plainly in better health, but with a fresh horizontal wrinkle between his brows, stood in civilian dress facing his father and Prince Meshchérski, warmly disputing and vigorously gesticulating. The conversation was about Speránski—the news of whose sudden exile and alleged treachery had just reached Moscow.

“Now he is censured and accused by all who were enthusiastic about him a month ago,” Prince Andrew was saying, “and by those who were unable to understand his aims. To judge a man who is in disfavor and to throw on him all the blame of other men’s mistakes is very easy, but I maintain that if anything good has been accomplished in this reign it was done by him, by him alone.”

He paused at the sight of Pierre. His face quivered and immediately assumed a vindictive expression.

“Posterity will do him justice,” he concluded, and at once turned to Pierre.

“Well, how are you? Still getting stouter?” he said with animation, but the new wrinkle on his forehead deepened. “Yes, I am well,” he said in answer to Pierre’s question, and smiled.

To Pierre that smile said plainly: “I am well, but my health is now of no use to anyone.”

After a few words to Pierre about the awful roads from the Polish frontier, about people he had met in Switzerland who knew Pierre, and about M. Dessalles, whom he had brought from abroad to be his son’s tutor, Prince Andrew again joined warmly in the conversation about Speránski which was still going on between the two old men.

“If there were treason, or proofs of secret relations with Napoleon, they would have been made public,” he said with warmth and haste. “I do not, and never did, like Speránski personally, but I like justice!”

Pierre now recognized in his friend a need with which he was only too familiar, to get excited and to have arguments about extraneous matters in order to stifle thoughts that were too oppressive and too intimate. When Prince Meshchérski had left, Prince Andrew took Pierre’s arm and asked him into the room that had been assigned him. A bed had been made up there, and some open portmanteaus and trunks stood about. Prince Andrew went to one and took out a small casket, from which he drew a packet wrapped in paper. He did it all silently and very quickly. He stood up and coughed. His face was gloomy and his lips compressed.

“Forgive me for troubling you....”

Pierre saw that Prince Andrew was going to speak of Natásha, and his broad face expressed pity and sympathy. This expression irritated Prince Andrew, and in a determined, ringing, and unpleasant tone he continued:

“I have received a refusal from Countess Rostóva and have heard reports of your brother-in-law having sought her hand, or something of that kind. Is that true?”

“Both true and untrue,” Pierre began; but Prince Andrew interrupted him.

“Here are her letters and her portrait,” said he.

He took the packet from the table and handed it to Pierre.

“Give this to the countess... if you see her.”

“She is very ill,” said Pierre.

“Then she is here still?” said Prince Andrew. “And Prince Kurágin?” he added quickly.

“He left long ago. She has been at death’s door.”

“I much regret her illness,” said Prince Andrew; and he smiled like his father, coldly, maliciously, and unpleasantly.

“So Monsieur Kurágin has not honored Countess Rostóva with his hand?” said Prince Andrew, and he snorted several times.

“He could not marry, for he was married already,” said Pierre.

Prince Andrew laughed disagreeably, again reminding one of his father.

“And where is your brother-in-law now, if I may ask?” he said.

“He has gone to Peters... But I don’t know,” said Pierre.

“Well, it doesn’t matter,” said Prince Andrew. “Tell Countess Rostóva that she was and is perfectly free and that I wish her all that is good.”

Pierre took the packet. Prince Andrew, as if trying to remember whether he had something more to say, or waiting to see if Pierre would say anything, looked fixedly at him.

“I say, do you remember our discussion in Petersburg?” asked Pierre, “about...”

“Yes,” returned Prince Andrew hastily. “I said that a fallen woman should be forgiven, but I didn’t say I could forgive her. I can’t.”

“But can this be compared...?” said Pierre.

Prince Andrew interrupted him and cried sharply: “Yes, ask her hand again, be magnanimous, and so on?... Yes, that would be very noble, but I am unable to follow in that gentleman’s footsteps. If you wish to be my friend never speak to me of that... of all that! Well, good-by. So you’ll give her the packet?”

Pierre left the room and went to the old prince and Princess Mary.

The old man seemed livelier than usual. Princess Mary was the same as always, but beneath her sympathy for her brother, Pierre noticed her satisfaction that the engagement had been broken off. Looking at them Pierre realized what contempt and animosity they all felt for the Rostóvs, and that it was impossible in their presence even to mention the name of her who could give up Prince Andrew for anyone else.

At dinner the talk turned on the war, the approach of which was becoming evident. Prince Andrew talked incessantly, arguing now with his father, now with the Swiss tutor Dessalles, and showing an unnatural animation, the cause of which Pierre so well understood.