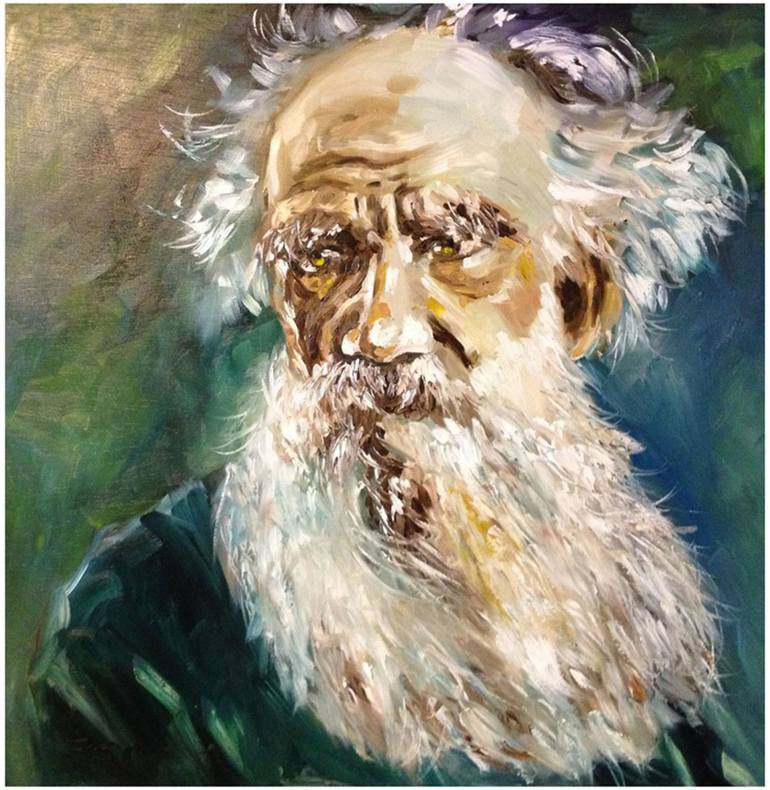

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1869

Source: Original Text from Gutenberg.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

During the entr’acte a whiff of cold air came into Hélène’s box, the door opened, and Anatole entered, stooping and trying not to brush against anyone.

“Let me introduce my brother to you,” said Hélène, her eyes shifting uneasily from Natásha to Anatole.

Natásha turned her pretty little head toward the elegant young officer and smiled at him over her bare shoulder. Anatole, who was as handsome at close quarters as at a distance, sat down beside her and told her he had long wished to have this happiness—ever since the Narýshkins’ ball in fact, at which he had had the well-remembered pleasure of seeing her. Kurágin was much more sensible and simple with women than among men. He talked boldly and naturally, and Natásha was strangely and agreeably struck by the fact that there was nothing formidable in this man about whom there was so much talk, but that on the contrary his smile was most naïve, cheerful, and good-natured.

Kurágin asked her opinion of the performance and told her how at a previous performance Semënova had fallen down on the stage.

“And do you know, Countess,” he said, suddenly addressing her as an old, familiar acquaintance, “we are getting up a costume tournament; you ought to take part in it! It will be great fun. We shall all meet at the Karágins’! Please come! No! Really, eh?” said he.

While saying this he never removed his smiling eyes from her face, her neck, and her bare arms. Natásha knew for certain that he was enraptured by her. This pleased her, yet his presence made her feel constrained and oppressed. When she was not looking at him she felt that he was looking at her shoulders, and she involuntarily caught his eye so that he should look into hers rather than this. But looking into his eyes she was frightened, realizing that there was not that barrier of modesty she had always felt between herself and other men. She did not know how it was that within five minutes she had come to feel herself terribly near to this man. When she turned away she feared he might seize her from behind by her bare arm and kiss her on the neck. They spoke of most ordinary things, yet she felt that they were closer to one another than she had ever been to any man. Natásha kept turning to Hélène and to her father, as if asking what it all meant, but Hélène was engaged in conversation with a general and did not answer her look, and her father’s eyes said nothing but what they always said: “Having a good time? Well, I’m glad of it!”

During one of these moments of awkward silence when Anatole’s prominent eyes were gazing calmly and fixedly at her, Natásha, to break the silence, asked him how he liked Moscow. She asked the question and blushed. She felt all the time that by talking to him she was doing something improper. Anatole smiled as though to encourage her.

“At first I did not like it much, because what makes a town pleasant ce sont les jolies femmes, * isn’t that so? But now I like it very much indeed,” he said, looking at her significantly. “You’ll come to the costume tournament, Countess? Do come!” and putting out his hand to her bouquet and dropping his voice, he added, “You will be the prettiest there. Do come, dear countess, and give me this flower as a pledge!”

* Are the pretty women.

Natásha did not understand what he was saying any more than he did himself, but she felt that his incomprehensible words had an improper intention. She did not know what to say and turned away as if she had not heard his remark. But as soon as she had turned away she felt that he was there, behind, so close behind her.

“How is he now? Confused? Angry? Ought I to put it right?” she asked herself, and she could not refrain from turning round. She looked straight into his eyes, and his nearness, self-assurance, and the good-natured tenderness of his smile vanquished her. She smiled just as he was doing, gazing straight into his eyes. And again she felt with horror that no barrier lay between him and her.

The curtain rose again. Anatole left the box, serene and gay. Natásha went back to her father in the other box, now quite submissive to the world she found herself in. All that was going on before her now seemed quite natural, but on the other hand all her previous thoughts of her betrothed, of Princess Mary, or of life in the country did not once recur to her mind and were as if belonging to a remote past.

In the fourth act there was some sort of devil who sang waving his arm about, till the boards were withdrawn from under him and he disappeared down below. That was the only part of the fourth act that Natásha saw. She felt agitated and tormented, and the cause of this was Kurágin whom she could not help watching. As they were leaving the theater Anatole came up to them, called their carriage, and helped them in. As he was putting Natásha in he pressed her arm above the elbow. Agitated and flushed she turned round. He was looking at her with glittering eyes, smiling tenderly.

Only after she had reached home was Natásha able clearly to think over what had happened to her, and suddenly remembering Prince Andrew she was horrified, and at tea to which all had sat down after the opera, she gave a loud exclamation, flushed, and ran out of the room.

“O God! I am lost!” she said to herself. “How could I let him?” She sat for a long time hiding her flushed face in her hands trying to realize what had happened to her, but was unable either to understand what had happened or what she felt. Everything seemed dark, obscure, and terrible. There in that enormous, illuminated theater where the bare-legged Duport, in a tinsel-decorated jacket, jumped about to the music on wet boards, and young girls and old men, and the nearly naked Hélène with her proud, calm smile, rapturously cried “bravo!”—there in the presence of that Hélène it had all seemed clear and simple; but now, alone by herself, it was incomprehensible. “What is it? What was that terror I felt of him? What is this gnawing of conscience I am feeling now?” she thought.

Only to the old countess at night in bed could Natásha have told all she was feeling. She knew that Sónya with her severe and simple views would either not understand it at all or would be horrified at such a confession. So Natásha tried to solve what was torturing her by herself.

“Am I spoiled for Andrew’s love or not?” she asked herself, and with soothing irony replied: “What a fool I am to ask that! What did happen to me? Nothing! I have done nothing, I didn’t lead him on at all. Nobody will know and I shall never see him again,” she told herself. “So it is plain that nothing has happened and there is nothing to repent of, and Andrew can love me still. But why ‘still?’ O God, why isn’t he here?” Natásha quieted herself for a moment, but again some instinct told her that though all this was true, and though nothing had happened, yet the former purity of her love for Prince Andrew had perished. And again in imagination she went over her whole conversation with Kurágin, and again saw the face, gestures, and tender smile of that bold handsome man when he pressed her arm.