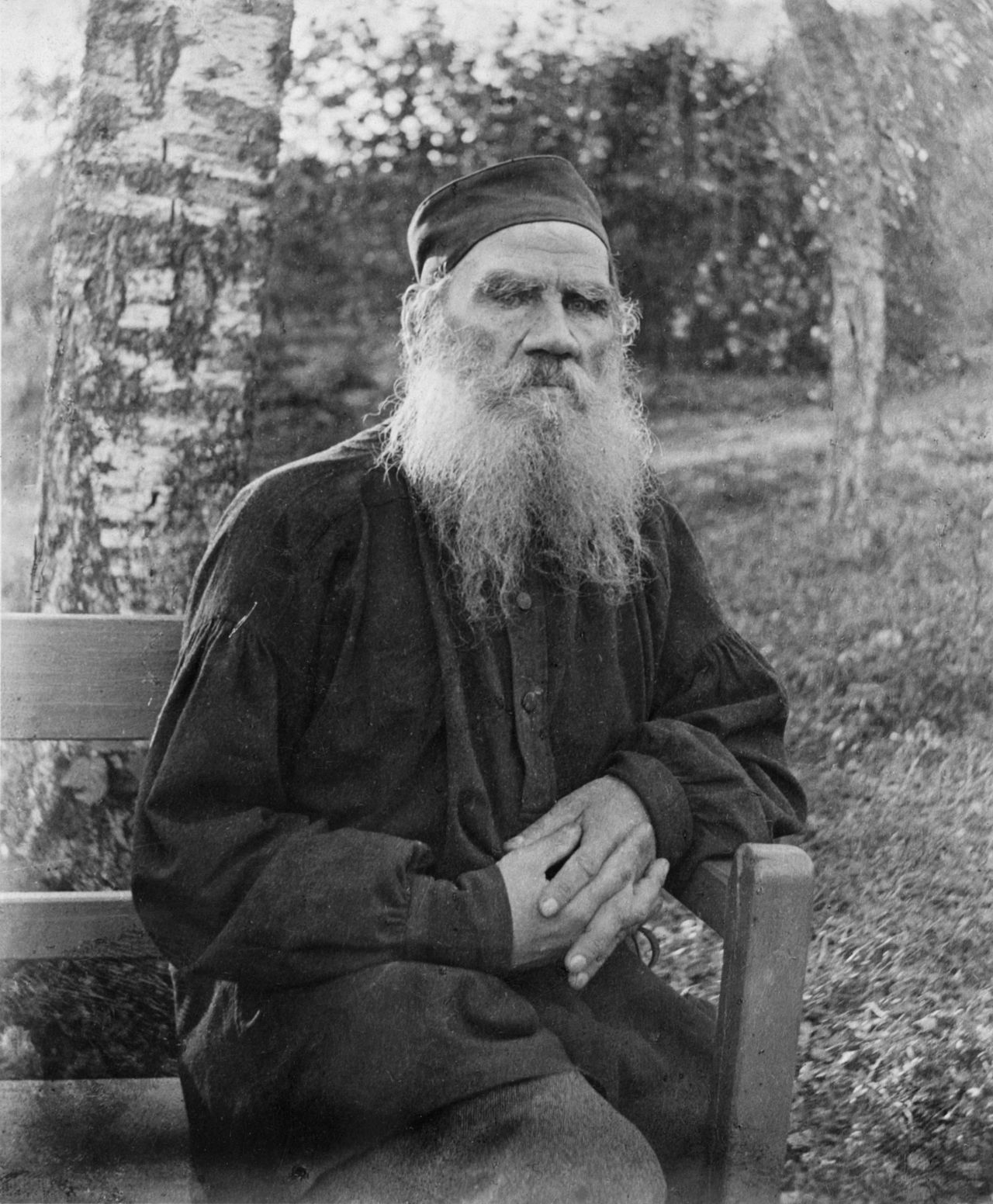

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1869

Source: Original Text from Gutenberg.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

Among the innumerable categories applicable to the phenomena of human life one may discriminate between those in which substance prevails and those in which form prevails. To the latter—as distinguished from village, country, provincial, or even Moscow life—we may allot Petersburg life, and especially the life of its salons. That life of the salons is unchanging. Since the year 1805 we had made peace and had again quarreled with Bonaparte and had made constitutions and unmade them again, but the salons of Anna Pávlovna and Hélène remained just as they had been—the one seven and the other five years before. At Anna Pávlovna’s they talked with perplexity of Bonaparte’s successes just as before and saw in them and in the subservience shown to him by the European sovereigns a malicious conspiracy, the sole object of which was to cause unpleasantness and anxiety to the court circle of which Anna Pávlovna was the representative. And in Hélène’s salon, which Rumyántsev himself honored with his visits, regarding Hélène as a remarkably intelligent woman, they talked with the same ecstasy in 1812 as in 1808 of the “great nation” and the “great man,” and regretted our rupture with France, a rupture which, according to them, ought to be promptly terminated by peace.

Of late, since the Emperor’s return from the army, there had been some excitement in these conflicting salon circles and some demonstrations of hostility to one another, but each camp retained its own tendency. In Anna Pávlovna’s circle only those Frenchmen were admitted who were deep-rooted legitimists, and patriotic views were expressed to the effect that one ought not to go to the French theater and that to maintain the French troupe was costing the government as much as a whole army corps. The progress of the war was eagerly followed, and only the reports most flattering to our army were circulated. In the French circle of Hélène and Rumyántsev the reports of the cruelty of the enemy and of the war were contradicted and all Napoleon’s attempts at conciliation were discussed. In that circle they discountenanced those who advised hurried preparations for a removal to Kazán of the court and the girls’ educational establishments under the patronage of the Dowager Empress. In Hélène’s circle the war in general was regarded as a series of formal demonstrations which would very soon end in peace, and the view prevailed expressed by Bilíbin—who now in Petersburg was quite at home in Hélène’s house, which every clever man was obliged to visit—that not by gunpowder but by those who invented it would matters be settled. In that circle the Moscow enthusiasm—news of which had reached Petersburg simultaneously with the Emperor’s return—was ridiculed sarcastically and very cleverly, though with much caution.

Anna Pávlovna’s circle on the contrary was enraptured by this enthusiasm and spoke of it as Plutarch speaks of the deeds of the ancients. Prince Vasíli, who still occupied his former important posts, formed a connecting link between these two circles. He visited his “good friend Anna Pávlovna” as well as his daughter’s “diplomatic salon,” and often in his constant comings and goings between the two camps became confused and said at Hélène’s what he should have said at Anna Pávlovna’s and vise versa.

Soon after the Emperor’s return Prince Vasíli in a conversation about the war at Anna Pávlovna’s severely condemned Barclay de Tolly, but was undecided as to who ought to be appointed commander in chief. One of the visitors, usually spoken of as “a man of great merit,” having described how he had that day seen Kutúzov, the newly chosen chief of the Petersburg militia, presiding over the enrollment of recruits at the Treasury, cautiously ventured to suggest that Kutúzov would be the man to satisfy all requirements.

Anna Pávlovna remarked with a melancholy smile that Kutúzov had done nothing but cause the Emperor annoyance.

“I have talked and talked at the Assembly of the Nobility,” Prince Vasíli interrupted, “but they did not listen to me. I told them his election as chief of the militia would not please the Emperor. They did not listen to me.

“It’s all this mania for opposition,” he went on. “And who for? It is all because we want to ape the foolish enthusiasm of those Muscovites,” Prince Vasíli continued, forgetting for a moment that though at Hélène’s one had to ridicule the Moscow enthusiasm, at Anna Pávlovna’s one had to be ecstatic about it. But he retrieved his mistake at once. “Now, is it suitable that Count Kutúzov, the oldest general in Russia, should preside at that tribunal? He will get nothing for his pains! How could they make a man commander in chief who cannot mount a horse, who drops asleep at a council, and has the very worst morals! A good reputation he made for himself at Bucharest! I don’t speak of his capacity as a general, but at a time like this how they appoint a decrepit, blind old man, positively blind? A fine idea to have a blind general! He can’t see anything. To play blindman’s bluff? He can’t see at all!”

No one replied to his remarks.

This was quite correct on the twenty-fourth of July. But on the twenty-ninth of July Kutúzov received the title of Prince. This might indicate a wish to get rid of him, and therefore Prince Vasíli’s opinion continued to be correct though he was not now in any hurry to express it. But on the eighth of August a committee, consisting of Field Marshal Saltykóv, Arakchéev, Vyazmítinov, Lopukhín, and Kochubéy met to consider the progress of the war. This committee came to the conclusion that our failures were due to a want of unity in the command and though the members of the committee were aware of the Emperor’s dislike of Kutúzov, after a short deliberation they agreed to advise his appointment as commander in chief. That same day Kutúzov was appointed commander in chief with full powers over the armies and over the whole region occupied by them.

On the ninth of August Prince Vasíli at Anna Pávlovna’s again met the “man of great merit.” The latter was very attentive to Anna Pávlovna because he wanted to be appointed director of one of the educational establishments for young ladies. Prince Vasíli entered the room with the air of a happy conqueror who has attained the object of his desires.

“Well, have you heard the great news? Prince Kutúzov is field marshal! All dissensions are at an end! I am so glad, so delighted! At last we have a man!” said he, glancing sternly and significantly round at everyone in the drawing room.

The “man of great merit,” despite his desire to obtain the post of director, could not refrain from reminding Prince Vasíli of his former opinion. Though this was impolite to Prince Vasíli in Anna Pávlovna’s drawing room, and also to Anna Pávlovna herself who had received the news with delight, he could not resist the temptation.

“But, Prince, they say he is blind!” said he, reminding Prince Vasíli of his own words.

“Eh? Nonsense! He sees well enough,” said Prince Vasíli rapidly, in a deep voice and with a slight cough—the voice and cough with which he was wont to dispose of all difficulties.

“He sees well enough,” he added. “And what I am so pleased about,” he went on, “is that our sovereign has given him full powers over all the armies and the whole region—powers no commander in chief ever had before. He is a second autocrat,” he concluded with a victorious smile.

“God grant it! God grant it!” said Anna Pávlovna.

The “man of great merit,” who was still a novice in court circles, wishing to flatter Anna Pávlovna by defending her former position on this question, observed:

“It is said that the Emperor was reluctant to give Kutúzov those powers. They say he blushed like a girl to whom Joconde is read, when he said to Kutúzov: ‘Your Emperor and the Fatherland award you this honor.’”

“Perhaps the heart took no part in that speech,” said Anna Pávlovna.

“Oh, no, no!” warmly rejoined Prince Vasíli, who would not now yield Kutúzov to anyone; in his opinion Kutúzov was not only admirable himself, but was adored by everybody. “No, that’s impossible,” said he, “for our sovereign appreciated him so highly before.”

“God grant only that Prince Kutúzov assumes real power and does not allow anyone to put a spoke in his wheel,” observed Anna Pávlovna.

Understanding at once to whom she alluded, Prince Vasíli said in a whisper:

“I know for a fact that Kutúzov made it an absolute condition that the Czarévich should not be with the army. Do you know what he said to the Emperor?”

And Prince Vasíli repeated the words supposed to have been spoken by Kutúzov to the Emperor. “I can neither punish him if he does wrong nor reward him if he does right.”

“Oh, a very wise man is Prince Kutúzov! I have known him a long time!”

“They even say,” remarked the “man of great merit” who did not yet possess courtly tact, “that his excellency made it an express condition that the sovereign himself should not be with the army.”

As soon as he said this both Prince Vasíli and Anna Pávlovna turned away from him and glanced sadly at one another with a sigh at his naïveté.