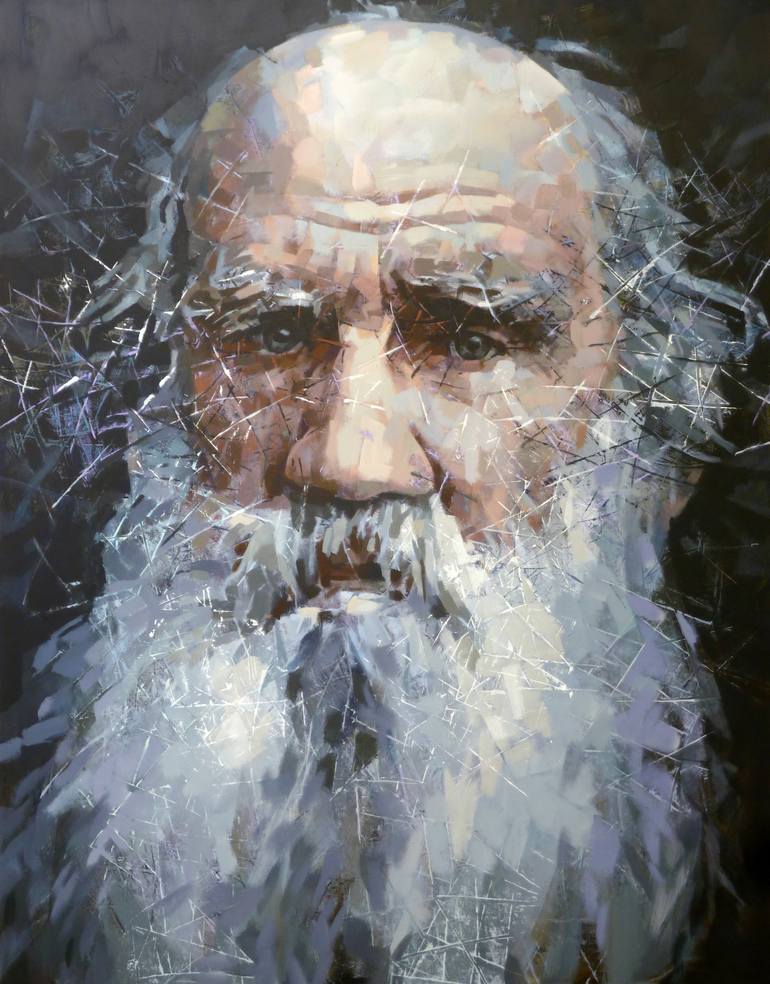

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1852

Source: The Cossacks: A Tale of 1852, by Leo Tolstoy, translated by Louise and Aylmer Maude, published 1863.

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

For two hours after returning home he lay on his bed motionless. Then he went to his company commander and obtained leave to visit the staff. Without taking leave of anyone, and sending Vanyusha to settle his accounts with his landlord, he prepared to leave for the fort where his regiment was stationed. Daddy Eroshka was the only one to see him off. They had a drink, and then a second, and then yet another. Again as on the night of his departure from Moscow, a three-horsed conveyance stood waiting at the door. But Olenin did not confer with himself as he had done then, and did not say to himself that all he had thought and done here was 'not it'. He did not promise himself a new life. He loved Maryanka more than ever, and knew that he could never be loved by her.

'Well, good-bye, my lad!' said Daddy Eroshka. 'When you go on an expedition, be wise and listen to my words—the words of an old man. When you are out on a raid or the like (you know I'm an old wolf and have seen things), and when they begin firing, don't get into a crowd where there are many men. When you fellows get frightened you always try to get close together with a lot of others. You think it is merrier to be with others, but that's where it is worst of all! They always aim at a crowd. Now I used to keep farther away from the others and went alone, and I've never been wounded. Yet what things haven't I seen in my day?'

'But you've got a bullet in your back,' remarked Vanyusha, who was clearing up the room.

'That was the Cossacks fooling about,' answered Eroshka.

'Cossacks? How was that?' asked Olenin.

'Oh, just so. We were drinking. Vanka Sitkin, one of the Cossacks, got merry, and puff! he gave me one from his pistol just here.'

'Yes, and did it hurt?' asked Olenin. 'Vanyusha, will you soon be ready?' he added.

'Ah, where's the hurry! Let me tell you. When he banged into me, the bullet did not break the bone but remained here. And I say: "You've killed me, brother. Eh! What have you done to me? I won't let you off! You'll have to stand me a pailful!"'

'Well, but did it hurt?' Olenin asked again, scarcely listening to the tale.

'Let me finish. He stood a pailful, and we drank it, but the blood went on flowing. The whole room was drenched and covered with blood. Granddad Burlak, he says, "The lad will give up the ghost. Stand a bottle of the sweet sort, or we shall have you taken up!" They bought more drink, and boozed and boozed—'

'Yes, but did it hurt you much?' Olenin asked once more.

'Hurt, indeed! Don't interrupt: I don't like it. Let me finish. We boozed and boozed till morning, and I fell asleep on the top of the oven, drunk. When I woke in the morning I could not unbend myself anyhow—'

'Was it very painful?' repeated Olenin, thinking that now he would at last get an answer to his question.

'Did I tell you it was painful? I did not say it was painful, but I could not bend and could not walk.'

'And then it healed up?' said Olenin, not even laughing, so heavy was his heart.

'It healed up, but the bullet is still there. Just feel it!' And lifting his shirt he showed his powerful back, where just near the bone a bullet could be felt and rolled about.

'Feel how it rolls,' he said, evidently amusing himself with the bullet as with a toy. 'There now, it has rolled to the back.'

'And Lukashka, will he recover?' asked Olenin.

'Heaven only knows! There's no doctor. They've gone for one.'

'Where will they get one? From Groznoe?' asked Olenin. 'No, my lad. Were I the Czar I'd have hung all your Russian doctors long ago. Cutting is all they know! There's our Cossack Baklashka, no longer a real man now that they've cut off his leg! That shows they're fools. What's Baklashka good for now? No, my lad, in the mountains there are real doctors. There was my chum, Vorchik, he was on an expedition and was wounded just here in the chest. Well, your doctors gave him up, but one of theirs came from the mountains and cured him! They understand herbs, my lad!'

'Come, stop talking rubbish,' said Olenin. 'I'd better send a doctor from head-quarters.'

'Rubbish!' the old man said mockingly. 'Fool, fool! Rubbish. You'll send a doctor!—If yours cured people, Cossacks and Chechens would go to you for treatment, but as it is your officers and colonels send to the mountains for doctors. Yours are all humbugs, all humbugs.'

Olenin did not answer. He agreed only too fully that all was humbug in the world in which he had lived and to which he was now returning.

'How is Lukashka? You've been to see him?' he asked.

'He just lies as if he were dead. He does not eat nor drink. Vodka is the only thing his soul accepts. But as long as he drinks vodka it's well. I'd be sorry to lose the lad. A fine lad—a brave, like me. I too lay dying like that once. The old women were already wailing. My head was burning. They had already laid me out under the holy icons. So I lay there, and above me on the oven little drummers, no bigger than this, beat the tattoo. I shout at them and they drum all the harder.' (The old man laughed.) 'The women brought our church elder. They were getting ready to bury me. They said, "He defiled himself with worldly unbelievers; he made merry with women; he ruined people; he did not fast, and he played the balalayka. Confess," they said. So I began to confess. "I've sinned!" I said. Whatever the priest said, I always answered "I've sinned." He began to ask me about the balalayka. "Where is the accursed thing," he says. "Show it me and smash it." But I say, "I've not got it." I'd hidden it myself in a net in the outhouse. I knew they could not find it. So they left me. Yet after all I recovered. When I went for my BALALAYKA—What was I saying?' he continued. 'Listen to me, and keep farther away from the other men or you'll get killed foolishly. I feel for you, truly: you are a drinker—I love you! And fellows like you like riding up the mounds. There was one who lived here who had come from Russia, he always would ride up the mounds (he called the mounds so funnily, "hillocks"). Whenever he saw a mound, off he'd gallop. Once he galloped off that way and rode to the top quite pleased, but a Chechen fired at him and killed him! Ah, how well they shoot from their gun-rests, those Chechens! Some of them shoot even better than I do. I don't like it when a fellow gets killed so foolishly! Sometimes I used to look at your soldiers and wonder at them. There's foolishness for you! They go, the poor fellows, all in a clump, and even sew red collars to their coats! How can they help being hit! One gets killed, they drag him away and another takes his place! What foolishness!' the old man repeated, shaking his head. 'Why not scatter, and go one by one? So you just go like that and they won't notice you. That's what you must do.'

'Well, thank you! Good-bye, Daddy. God willing we may meet again,' said

Olenin, getting up and moving towards the passage.

The old man, who was sitting on the floor, did not rise.

'Is that the way one says "Good-bye"? Fool, fool!' he began. 'Oh dear, what has come to people? We've kept company, kept company for well-nigh a year, and now "Good-bye!" and off he goes! Why, I love you, and how I pity you! You are so forlorn, always alone, always alone. You're somehow so unsociable. At times I can't sleep for thinking about you. I am so sorry for you. As the song has it:

"It is very hard, dear brother, In a foreign land to live."

So it is with you.'

'Well, good-bye,' said Olenin again.

The old man rose and held out his hand. Olenin pressed it and turned to go.

'Give us your mug, your mug!'

And the old man took Olenin by the head with both hands and kissed him three times with wet mustaches and lips, and began to cry.

'I love you, good-bye!'

Olenin got into the cart.

'Well, is that how you're going? You might give me something for a remembrance. Give me a gun! What do you want two for?' said the old man, sobbing quite sincerely.

Olenin got out a musket and gave it to him.

'What a lot you've given the old fellow,' murmured Vanyusha, 'he'll never have enough! A regular old beggar. They are all such irregular people,' he remarked, as he wrapped himself in his overcoat and took his seat on the box.

'Hold your tongue, swine!' exclaimed the old man, laughing. 'What a stingy fellow!'

Maryanka came out of the cowshed, glanced indifferently at the cart, bowed and went towards the hut.

'LA FILLE!' said Vanyusha, with a wink, and burst out into a silly laugh.

'Drive on!' shouted Olenin, angrily.

'Good-bye, my lad! Good-bye. I won't forget you!' shouted Eroshka.

Olenin turned round. Daddy Eroshka was talking to Maryanka, evidently about his own affairs, and neither the old man nor the girl looked at Olenin.

The End