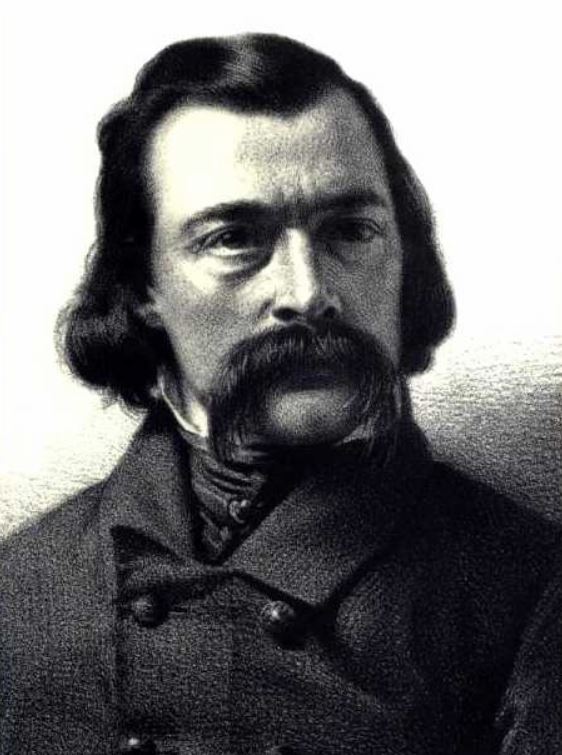

Victor Considerant Archive

Victor Considerant was born in Salins (Jura) in 1808, and attended the same collège in Besançon as had Charles Fourier. During these years he learned of Fourierism from two followers: Just Muiron, a local government official, and Clarisse Vigoureux, a wealthy widow, his future mother-in-law. Considerant continued his education at the École Polytechnique in Paris, where he studied engineering. Here the ideas of Henri-Claude de Saint-Simon were in vogue, and Considerant became well acquainted with them. Like many of his fellow students, he joined the military engineering corps upon graduation in 1830. By then, he was already a Fourier publicist, and in 1836 he gave up his career to become Fourier’s full-time disciple and interpreter.

Considerant followed his master in seeking harmony and class collaboration, and rejecting violence and radical equalization of property. They were both outraged at the consequences of a “free enterprise” system, which was creating poverty among rural and urban workers, constant insecurity for the middle class, and a new aristocracy of monopolists and speculators. It was not coincidental that Considerant was an engineer; those so trained were receptive to planning and formed an important core of nineteenth century French socialism.

Although Considerant revered science, he also had faith in human goodness and Jesus’ message of love. In contrast, Fourier’s religion had been his own version of deism: passionate attraction was God’s plan for humanity’s salvation. Understanding this, as Fourier did, “social scientists” could transform disruptive passions into harmony. Considerant suggests a Christian socialist approach, one of his radical emendations of Fourier.

Considerant continued to publish detailed expositions of Fourier’s phalanstery, which had been an important recruitment tool. Nevertheless, in his popular presentations, he increasingly de-emphasized all but its economic virtues. This eliminated the shocking and fantastic elements, but also much of Fourier’s brilliant social criticism. Socialism as a product of the Enlightenment aimed at all the institutions stifling human happiness and wellbeing, including war, status distinctions, slavery, political oppression, organized religion, marriage, and fashion, in addition to irrational and oppressive economic systems. Much of Fourier’s oeuvre parodies these institutions; hardly any of this remains in the sober Considerant. Perhaps the most striking omission was his evisceration of Fourier’s radical feminism. Considerant did support women’s suffrage, yet his heart does not seem to have been in it.

The strange twist that gave Fourierism its opportunity was that in the 1820s some self-proclaimed leaders of the originally technocratic Saint-Simonian movement adopted cultish and bizarre practices and notions, such as a search for a female Messiah. Saint-Simonianism had a large following by 1831 (approximately 40,000) when massive defections to Fourierism began, especially among the engineers and other practically minded adherents. However, some of the potential philanthropists saw the phalanstery merely as a practical plan for the amelioration of poverty and unemployment. They envisioned it as a model farm or an agricultural colony to provide employment and subsistence rather than a cross-class experiment in utopia.

The transformation of Fourierism was also abetted by technological changes. Just as Ebenezer Howard’s late 19th century charming and rational Garden City schemes were ultimately derailed by the private automobile, the thrill of railroads in the 1840s sidetracked the anarchic phalanstery in favor of national planning bureaucracies.

During the 1830s and 1840s, under Considerant’s leadership, the École sociétaire, the official Fourierist society, had branches throughout in Europe and the United States. An “American Union of Associationists” was formed, with local and regional groups, and had more than 100,000 followers. Fourierism also became an important ideology among radical intellectuals in Russia.

Fourierism was a “cross-class” solution to the economic chaos and distress, promising also to realize democracy by uniting rich, middle, and poor. It was attractive to recruits from freemasonry, which had similar goals. Many women became supporters; they were often highly educated, but lacked status in French society. Considerant himself had been recruited by his future mother-in-law, Clarisse Vigoureux.

Considerant lectured, wrote, and edited publications; popularizations of Fourier’s ideas sold well, even among working class readers. However, he showed little enthusiasm for creating a trial phalanstery, although other Fourierists attempted this in France (1832 and 1841) and Algeria (1845), without much success. The United States was a more fertile ground, and scores of experiments in Fourierism ensued, stimulated especially by Albert Brisbane’s expositions in The Social Destiny of Man, or Association and Reorganization of Industry (Philadelphia, 1840), pamphlets, and a purchased front-page daily column in the New York Tribune (1842-1843). Brisbane had absorbed and transmitted the milder version of Fourierism from correspondence and visits to Considerant. \

By the mid-1830s, Considerant began to regard working class movements and electoral politics as the paths to reform. His journalism and practical activities were moving in this new direction; nevertheless, he continued to work on his massive exposition of Fourier doctrine: Destinée sociale, published in three volumes between 1834 and 1844. In 1843 he was elected to the Parisian local government council, and in the same year he transformed the Fourierist journal, La Phalange, into a new daily newspaper, La Démocratie pacifique. It was designed as an organ for a political socialist movement, shorn of all Fourierist peculiarities. Considerant wrote his Manifeste for the 1843 introductory issue of the newspaper; it was reprinted as a pamphlet in 1847.

La Démocratie pacifique was a general newspaper, with advertisements, theater listings, crime reports, and much commentary on current news; its circulation reached 2,200. At that time, such newspapers were a new development, and their survival depended on donations from enthusiasts. It still championed the idea of “association,” yet the phalanstery as the road to socialism was soft-pedaled in favor of broad “New Deal-like” state action, including guarantees of the right to work, public works projects, and central economic planning. Even the term phalanstery was omitted in favor of “commune,” meaning “town” (without any of the later hippie connotations).

The 1848 Revolution gave Considerant great hope that his theories might be realized; he contested and won a seat in the National Assembly. He then served on committees devoted to the unemployment crisis, yet he had no success in either advancing reformist goals or spreading the Fourierist word. Considerant’s experience led him to advocate direct democracy, such as legislation by referendum rather than representative assemblies. His continued condemnation of the communist tendency, for both its methods and goals, kept him apart from the working class.

Considerant played a major role in an 1849 protest action against the government’s plan to engineer a regime change for the Roman Republic. The insurrection was put down, some violence ensued, and he was forced to flee, becoming an exile in Belgium where he spent much time fishing. There he decided that it might be a propitious time for a trial phalanstery. Brisbane had met with him and invited him to the United States. Considerant accepted the offer, and began his tour with visits to the North American Phalanx and Oneida communities.

In 1852 he arrived in Texas, and in 1855 Considerant bought land near Dallas, intending to create a colony that would host various communal experiments, not only Fourierist ones. The preparation had been inadequate, and the environment hostile both physically and politically. Nevertheless, colonists began arriving from France, including children, elderly, and inappropriately skilled. Considerant was inept as an administrator, despite his military engineering education, and the colony, called Réunion, disintegrated amidst acrimony and lack of hominy (malnutrition). His wife and mother-in-law might have been more effective managers, but they were sidelined; he did not seem to share the Fourierist appreciation for the genius of women.

In 1857, Considerant moved to San Antonio, where he farmed, collected cacti, and sat out the Civil War. Upon his return to France in 1869, he was still celebrated by the surviving Fourierists. By then he had been influenced by Social Darwinism, and advocated a federated Europe, in concert with the United States, to serve as a benevolent world government. He joined the First International, and took part in the 1871 Paris Commune. He kept his faith in socialism and pacifism, and died in 1893.

(For more information, off-site: Jonathan Beecher, Victor Considerant and the Rise and Fall of French Romantic Socialism, University of California Press, 2001).