The idea of a general strike as a method of last resort had long existed inside the Labour movement. It was first proclaimed by the Chartist Convention in February 1839 in a situation of mounting social tension. For nearly twenty years the British workers had fought, in alliance with the middle class, for a wide extension of the franchise, but the fruits of their joint struggle—the Reform Act of 1832—went entirely to the middle class, without the workers securing a single concession. At the height of the campaign, the middle class had employed its own version of the strike weapon by organizing a run on the banks, and had succeeded brilliantly. In contrast, the working class, employing the traditional techniques of meetings, demonstrations and petitions to Parliament, had failed completely. From then on the idea of a general strike began to gain ground. From the earliest days of Chartism in the 1830s it was under discussion as a possible means of bringing pressure to bear on the ruling class. When the first Chartist petition, calling for universal male suffrage, with more than 2,283,000 signatures, was rejected by Parliament, a general strike was in fact proclaimed, but the response was feeble. Three years later, when the second Chartist petition, with over 3,300,000 signatures, was also rejected, a strike broke out among hundreds of thousands of workers in the industrial north.[1]

This was the first large-scale political strike in the history of the Labour movement. It broke out spontaneously, with no preconceived plan. Starting at the beginning of August 1842, it lasted for three weeks. The financial reserves of the unions were too meagre to support the strikers and hunger forced them back to the mines and factories.

Leading Chartists had foreseen the outcome. Some of them, for this reason, had spoken in Chartist congresses and written in the Chartist Press against calling a strike. Others had supported a strike, in the hope that it would touch off an armed uprising which would usher in the social revolution. Yet others saw in even an unsuccessful strike a useful means of awakening the class consciousness of the masses and so paving the way for revolution. All aspects of the general strike—as an instrument for seizing power, as a lever of insurrection, as a weapon in the fight for immediate political aims, as a 'revolutionary exercise', as a method of 'propaganda by deed'—were, a full half-century before French Socialists discussed such concepts theoretically and Belgian Socialists applied them in practice, discussed by the Chartists. 'There is a decidedly contemporary feel about the situation,' wrote Max Beer in his description of the Chartist debates on the general strike.[2]

After the failure of Chartism, the British workers abandoned the idea of the general strike. Its revival in the European Labour movement was the direct outcome of the Anarchist movement in the late 1860s. The question came up at the Brussels Congress of the First International in 1868, as to whether the working class could prevent wars. To the great astonishment of Marx, a resolution introduced by the Belgian and French delegates and passed without a division declared simply: 'Since no society can exist when production is stopped for any length of time…it is therefore sufficient to cease work for a war to be made impossible.' It called on the workers, therefore, 'to cease work in the event of war breaking out in their country'.

By the time of the Second International, the problem was beginning to be seen in its full complexity as one requiring considerable thought. It was raised briefly at the Inaugural Congress in Paris in 1889, when a French delegate wanted to add to the resolution on May Day a rider proclaiming it a day of general strike 'to mark the beginning of the social revolution'. The suggestion came shortly before the end of the congress when detailed discussion was impossible. Only Liebknecht referred to it, claiming that it 'was an impossibility', since a general strike required a degree of working-class organization 'unattainable in bourgeois society'. After that the proposal was withdrawn.

It was only at the following congress, held in Brussels in 1891, that the International began its first serious debate on the problem of the general strike. And once again the discussion was subordinated by the wider problem—which came up again and again in the history of the International—of whether it was feasible for the working-class movement to prevent war by its own efforts. On this occasion the debate[3] took place on a motion by Domela Nieuwenhuis, who proposed that 'a threatened declaration of war should be answered by an appeal to the people for a general cessation from work'. Thirteen out of the sixteen national delegates present rejected the general strike as a possible means for avoiding wars, with only the Dutch and a majority of the English and French voting for the resolution.

Meanwhile Belgium had experienced a series of exceedingly widespread strikes among the workers, in 1886, 1887, 1891 and 1893. They were distinctive in being political strikes in support of a demand for universal suffrage. The strikes of 1886 and 1887 were spontaneous explosions, touched off by a campaign in Alfred Defuisseaux's militant paper, Le Catéchisme du people. Those of 1891 and 1893 took place in response to an appeal by the party, which had approved the general strike as a weapon in the campaign for the franchise at its congress in 1891.

The general strikes in Belgium, particularly that of 1893, showed that they were by no means such 'impossibilities' as Liebknecht had imagined. The workers had succeeded in paralysing the country's economy and blasting open the gates which had hitherto kept them out of Parliament. They had proved conclusively that the general strike was a valuable weapon in the armoury of the working class. In the light of this experience, the representatives of French trade unionism asked for the question of a 'world strike' to be put on the agenda of the International's Zurich Congress in 1893.

The proposal went to a commission of the congress for preliminary discussion. A resolution drafted by Kautsky opposed the idea of a 'world strike' on the grounds of impracticability, 'due to the unevenness of economic development in the various countries'. It stated, however, that a general stoppage called in particular industries 'could in certain conditions be a most effective weapon of political as well as economic struggle'. Owing to the pressure of business, the item was not reached on the agenda. Nevertheless, it was on record that a commission of the congress had recognized the mass strike as a legitimate weapon of political warfare.

The French trade-union leaders could hardly be satisfied with the way in which their proposal had been dealt with at Zurich. They therefore put it down for debate at the next congress, in London, in 1896. While admitting that a world-wide strike seemed impracticable, they argued that this did not apply to a general strike called in a particular country, and they insisted that the question be seriously discussed. They proposed that member parties and unions should be asked to study the question and debate it at the following congress. Once again, however, the proposal, which was passed to a commission, was not reached on the congress agenda. Eugène Guérard protested, on behalf of the French trade unions, against the fact that a question of the greatest importance to French workers—since, he said, they considered the general strike to be 'the most revolutionary weapon' they possessed—had not been considered worthy of debate. And he announced that it would again be put down for discussion at the following congress.

The question of the general strike was, indeed, of crucial importance to the French trade-union movement. At one congress safter another—at Marseille in 1892, Paris in 1893, Nantes in 1894 and Limoges in 1895—the Fédération Nationale des Syndicats Ouvriers had discussed the general strike and supported it with growing emphasis. For the French unions the general strike was not a weapon for securing political objectives. They rejected all forms of parliamentarism, including the revolutionary Marxist version propounded by the Guesdists. The general strike was for them the lever of social revolution.

Syndicalism—the theory that the workers should wage the class struggle entirely by industrial means—was an expression of disillusionment with politics as a means of solving social problems. France was admittedly a parliamentary democracy, with universal and equal franchise for all adult males. But parliamentary democracy was far from having satisfied the revolutionary hopes of the working class, and in their impatience they rejected parliamentarism in its entirety. To them the struggle of the Socialists for parliamentary power seemed not only useless but harmful, since it diverted energy from the class struggle and so weakened the revolutionary impulses of the workers and demoralized the trade unions. Parliamentary activity, they asserted, led inevitably to corruption and opportunism, while all politics provided a jumping-off ground for chatterers, charlatans and careerists. The workers must rely on their own strength, since only 'direct action' based on industrial organization could free them from capitalist domination.[4] Syndicalism shared with the Anarchists the view that the power of the state must not be seized, but destroyed. What would follow would be, not a Socialist state, but a Socialist commonwealth without any state, resting on the organization and activity of the unions.

The conflict between revolutionary Syndicalism and Marxism over parliamentarism, the need for political action and the role of the general strike, had been a feature of French trade-union congresses since 1892. It shook and finally destroyed the unity of the French Labour movement. The breach between the unions and the Socialist party was effected at the Nantes Congress in September 1894. The 'indestructible union' between the Socialist movement and the unions which Jules Guesde thought he had established at the Marseille Congress in 1879 had already disintegrated.

At the Nantes congress, Jules Guesde had gone down after a bitter struggle against Ferdinand Pelloutier, the intellectual progenitor of Anarcho-Syndicalism. Pelloutier (1876–1901) was of middle-class origin. His father had been a post-office official, his grandfather a lawyer and his great-uncle a baron. While still a young man, he had taken to politics with considerable ardour. Beginning as a radical journalist, he soon joined the Guesdists. Disillusioned, however, by the apparent futility and compromise of parliamentarism, he moved closer to the Anarchist ideology. He saw in the unions the germ cells of the coming Socialist order, and in the general strike the lever of the Socialist revolution. In numerous articles and pamphlets he expounded the character and structure of the Socialist community as he envisaged it—a stateless society based on a federation of producers organized in industrial unions. The theory which emerged from his writings became known as Anarcho-Syndicalism.[5]

In 1894 Pelloutier became secretary of the Fédération Nationale des Bourses de Travail—the national federation of trades councils, originally known as labour relations offices, which gradually became the focal points of the social and political life of the Labour movement. When, a year later, at the Limoges Congress in 1895, the trade unions united to form the Confédération Générale du Travail (C.G.T.), the national federation of trades councils joined the C.G.T. as an autonomous organization, but later merged with it completely at the 1902 congress in Montpellier. The C.G.T. was, from then on, the organized expression of Revolutionary Syndicalism.

In 1898 Victor Griffuelhes (1874–1923) became secretary of the C.G.T. He was a shoemaker by trade, a tough, audacious, class-conscious trade-union leader of Blanquist convictions, who combined Revolutionary Syndicalism with the characteristic Blanquist view of the 'conscious minority' whose mission it was to mobilize and lead the 'dull masses'. His chief colleague was Émile Pouget (1860–1932), who edited the trade-union paper, La Voix du people. Pouget was a talented journalist of fanatically Anarchist views, and the most important representative of the concept of the 'revolutionary exercise', seeing the C.G.T. as principally a 'training school' for preparation for the revolution.

The trade-union congress at Nantes in 1894 had established a separate committee with its own finances and special powers to prepare for a general strike. According to the Anarcho-Syndicalists the general strike would serve as the final signal for revolution, leading directly to the seizure of factories and mines by the workers and the economic dispossession of the capitalists. Prior to this, however, it was the function of general strikes to train the workers for revolution, to strengthen their class solidarity and militancy—to serve, in fact, as 'revolutionary exercises'. In the 'myth of the general strike', as expounded by Georges Sorel,[6] the Syndicalists discovered a source of inspiration which, they were convinced, could arouse the untapped creative power of the masses. According to Sorel, the motive force of all the great renovating movements in history—the early church, the French Revolution, the Italian Risorgimento—was a social myth, some non-rational concept of perfection which inspired an 'epic state of mind'. The major social changes in history had all resulted from conflicts between the social values of the myth and those of existing society. In Sorel's doctrine the social myth of the general strike was the essential dynamic which would regenerate society through social revolution and shatter the capitalists and their state. The theory made a deep impression on the minds of the leading Syndicalists.

The Syndicalists had no doubt about the invincible power of the general strike. Despite its enormous physical power, the capitalist state would be unable to withstand such a combined attack by the workers. A detailed illustration of this was provided by Eugène Guérard, speaking in 1896:

In an attempt to defend factories, workshops and warehouses, the army would disperse its forces [he explained]. The mere threat by the workers to destroy railway lines and signalling equipment would compel the government to spread its troops over 39,000 kilometres of the French railway system. An army of 300,000 men defending 39 million metres of railway track would mean one man to every 130 metres, with 130 metres separating each man from his neighbour. In these conditions the government would be unable to protect the warehouses and factories. The factories would be left undefended and the revolutionary workers in the towns would have the field to themselves.[7]

As Eugène Guérard had told the London Congress, the French delegation put the question of the general strike on the agenda once again at the Paris Congress in 1900. In the name of the trade-union representatives, the Allemanists and the followers of Jaurès, they moved a resolution requesting Congress to appeal to 'the workers of the whole world to organize for the general strike', which would serve as a 'lever' for 'exerting pressure on capitalist society indispensable for securing the necessary political and economic reforms'. Under suitable conditions the general strike could also be 'used in the service of the revolution'.

The mover of the resolution at the congress was Briand, a friend of Pelloutier. Briand was an enthusiastic advocate of the idea of the general strike. He had submitted a resolution about it to the trade-union congress at Marseille in 1892 and defended it against Guesde at the Nantes Congress in 1894. He did more than anyone else to introduce the idea of the general strike in the International. He saw in the idea, as he told the Paris Congress, the 'form of revolutionary action' for the entire trade-union movement most appropriate to the conditions of working-class struggle against capitalism. He said in Paris, as at Nantes: 'For me the general strike is a technique of revolution, but of a revolution which offers more guarantees than those of the past, a revolution which will not permit individuals to appropriate the fruits of victory, but will make it possible for the proletariat to take hold of the productive resources of society once and for all.'[8] However, most of the delegates at Congress were more sceptical about the success of a general strike. Karl Legien, the main architect of trade unionism in Germany, replying to Briand, said that the first prerequisite for a general strike was a powerful, mass trade-union organization. 'For the bourgeoisie,' he declared, 'a general strike by unorganized masses would be a gift; they would suppress it in a few days, if necessary by force of arms, and so destroy the work of decades.' With a certain condescension he added: 'Let our French and Italian comrades achieve the necessary organization and we shall certainly stand by them.'

The resolution down in the name of Briand, Alleman and Jaurès was supported by only one vote each from France, Italy and Russia and by two each from Portugal and Argentina. The majority resolution endorsed the decision of the commission of the London Congress, which had acknowledged 'strikes and boycotts as necessary means of achieving working-class aims' while rejecting the idea of the international general strike. Both congresses, London as well as Paris, avoided a discussion of the national general strike and its significance for the Labour movement.

Meanwhile, in a number of countries, such as Belgium, Sweden and Holland, the general strike had become an acute problem, and once again it was Belgium which supplied the impetus. By the general strike of 1893 the Belgian workers had won the right to parliamentary representation. But the struggle had ended in a compromise based on a system of plural voting which ensured that the working-class representatives would always be outnumbered by the clericals. In the struggle for an equal franchise, the Liège Party Congress in April 1901 agreed to employ 'if necessary, the general strike and street fighting'.

Exactly a year later, on 12 April 1902, insurrections broke out in the streets of Belgian towns. They had broken out spontaneously, without any call from the party, as a result of heated parliamentary debates on electoral reform between working-class and clerical representatives. According to Vandervelde, 'the parliamentary agitation was reflected at stormy meetings in the main towns. When right-wing deputies came home in the evenings from a parliamentary session they were met at the railway stations by hostile crowds. Everywhere workers poured on to the streets.'[9] In blood clashes, workers exchanged fire with police and gendarmerie, whereupon the party called on the workers to stop the fighting and stay away from work.

The government, however, was well-prepared for the clash. It had reinforced its 60,000 garrison troops by calling up several groups of reservists and mobilizing the civil guard. On the evening of 18 April, when it was announced that the Chamber had rejected the electoral reform bill, there were again stormy demonstrations and clashes between workers and members of the armed forces. In Loewen the civil guard opened fire on demonstrators, killing six and wounding many more.

It was now clear that there was no way of continuing the strike which did not involve starting a civil war, and the party's General Council was faced with the stark alternative of preparing for an armed uprising or calling off the strike. In view of the overwhelming superiority of the armed forces at the disposal of the state, the party could not bring itself to call for revolution; but it had also to face the fact that to break off the general strike would be to admit defeat and could well both demoralize the movement and gravely weaken the party itself. On the other hand, it could not risk the unforeseeable hazards of a civil war, especially in view of its own explicit commitment to legal forms of struggle. On 20 April the party issued a simple request to the strikers to go back to work.

There then occurred one of the most surprising developments in the history of social conflict. The withdrawal from a contest which had engaged the most profound emotions of the workers took place in a calm and orderly manner. At the call of the party the workers resumed work in mine and factory with the same discipline they had shown when they had first downed tools. The party had undoubtedly suffered a defeat, but it was not a catastrophe. Contrary to Legien's fears of the consequences of an unsuccessful general strike, the party was not destroyed. On the contrary, the workers tended, if anything, to draw closer to it.

In the following month the Swedish Social Democrats also employed the general strike in a campaign for the franchise, though in an entirely novel way. The strike was not, as in Belgium, permitted to break out spontaneously. Before it was even announced, the main details of the strike, including its termination, were carefully planned. The decision to use the general strike in this way had been decided as early as the Göteborg Congress in 1894. But at that time the party was still weak and there was no central trade-union body until the Lands-Organisation (L.O.) was established in 1898. At the turn of the century, moreover, the Labour movement in the north of Sweden was preoccupied with severe struggles to secure trade-union recognition.

The movement began to turn its attention once again to the struggle for the franchise when, at the beginning of 1902, the government, acting under pressure of persistent agitation by Social Democrats and Liberals, presented a draft reform bill to the Rigsdag (Parliament). This, while increasing the number of those eligible to vote, still excluded a substantial majority of the workers. The party responded by calling mass demonstrations against the draft, while asking the workers to cease work for the three days beginning on 15 May—the day the bill came before the Rigsdag. As a strike it was a complete success. Industry and transport were paralysed for three days. The strike, which was intended to display the strength and solidarity of the working class, fulfilled its purpose admirably. But as a means of bringing pressure on the Conservative majority in the Rigsdag it failed completely. The general strike of 1902, therefore, was merely an episode in the struggle of the Swedish workers for the right to vote under conditions of universal suffrage—a right they were not to obtain for another seven years.

On the other hand, in Holland, an attempt at a general strike in April 1903 not only ended in failure, but caused a considerable set-back to the already divided Socialist movement. It had begun with a spontaneous strike of railway workers at the end of January, in protest against being required to blackleg in a dock strike. The government, unable to compel railwaymen to replace dockers, withdrew the order. But the success was shortlived. The government immediately introduced a draft law to deprive all workers in state employment, including the railwaymen, of the right to strike.

The proposal met with an angry response from the workers. The two parties into which the Dutch movement had split—the Sociaaldemokratisch Parti in Nederland (S.D.P.) and the Sociaaldemokratisch Arbeid Parti (S.D.A.P.)—set up a joint defence committee, which threatened to call out the entire working class of Holland in defence of the freedom to strike. Troelstra, president of the S.D.A.P., who had proposed the resolution at a meeting of the defence committee, called on the workers, in Het Volk, to 'make all preparations to respond at once to the appeal of the defence committee with a tremendous strike, which will demonstrate to the world that the Dutch workers would rather go down fighting than be trampled on'. The government seemed unmoved by the threat and the strike was duly called. There followed the most severe clashes between the workers and the state machine in Dutch history. The defence committee was prepared neither to push matters to extremes nor to call off the strike, and the movement accordingly fell to pieces. The defeat worsened and embittered relations between the two Socialist parties represented a disastrous set-back for the trade-union movement.

Experiences in Belgium and Holland had shown the general strike to be a double-edged weapon. In both countries the leadership had soon been faced with the dilemma of either developing the struggle to the point of insurrection or retreating. However, in neither Belgium nor Holland had the leaders of the strike seriously contemplated resorting to illegality, much less calling an armed uprising. But if the fight were to be waged within limits imposed by the law, the government, with its tremendous apparatus of power, was much better placed than the workers. In both cases, therefore, it was the working class and not the government which had withdrawn. From all of which the conclusion was readily drawn that the general strike should be regarded as the ultima ratio, the final resort in a crisis, the most extreme measure open to the workers in a pre-revolutionary situation. It should not, therefore, be attempted unless the working class was prepared for a fight to the finish.

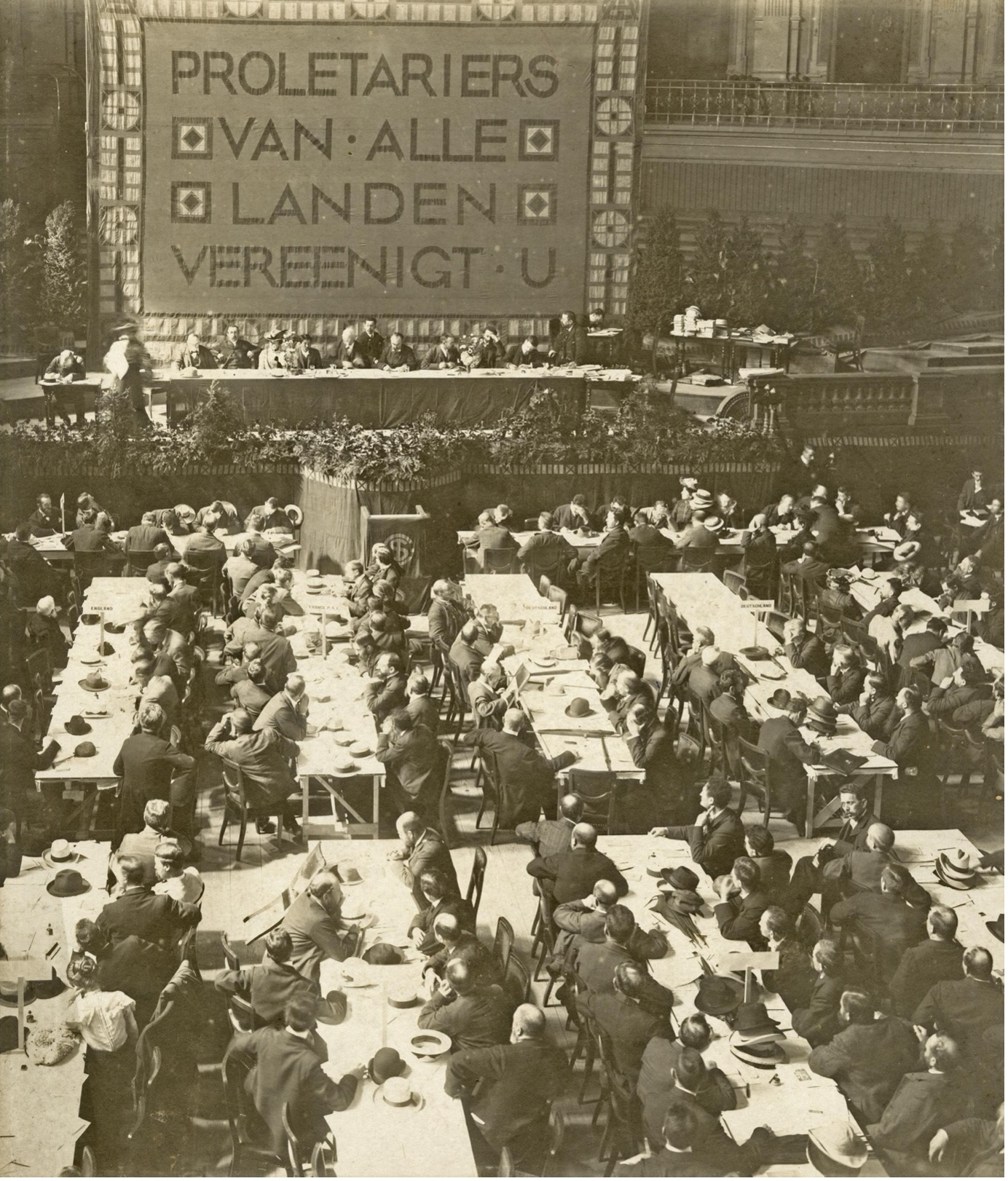

These were no doubt the considerations in the minds of most delegations when the general strike came up for debate at the Amsterdam Congress of the International in August 1904, although the question of legality was not explicitly broached. The Allemanists and the Jaurès group had put the question on the agenda. Jaurès himself had doubts about the value of a general strike. But he was mainly concerned to secure as great as possible a degree of unity between the party and the unions, and since the general strike played such a prominent part in the thinking of the unions in France he voted in favour of a resolution which requested the parties of the International to study 'the rational and systematic organization of the general strike'.

The resolution was formally proposed, both in commission and in open congress, by Briand, who argued that the question of the general strike was simply one of tactics. If Congress approved the tactics of the class struggle, it must necessarily approve the general strike, which was merely, so far as the workers were concerned, its ultimate expression. The general strike was a means of exerting pressure on capitalism to concede reforms, and a means by which the workers could fight when deprived of political rights. 'There is talk of a threat to take away universal suffrage in Germany,' Briand declared. 'In that case what weapon would remain to the working class other than the general strike?'

The resolution supported by a majority of the commission and presented to Congress by Henriette Roland-Holst drew a distinction between general strikes and mass strikes. A 'complete general strike' she believed to be impracticable, 'since it makes the existence of everyone, including the proletariat, impossible'. However, the commission considered a mass political strike to be advisable under certain conditions, but only as 'a last resort, in order to secure important social changes or to resist reactionary attempts on the rights of the working class'. The resolution warned the workers against 'propaganda for the general strike emanating from Anarchist sources' which was intended to 'divert the workers from conducting limited though important struggles by means of trade-union, political or co-operative action'. It appealed to the workers 'to strengthen their unity and attain positions of power in the class struggle through developing their organizations', since it was on organization that the success of a mass political strike would depend, should that be 'found necessary and expedient'. The contorted prose of the resolution hardly served to conceal the doubts felt in many parties about the value of the mass political strike, and their extreme reluctance to think through the implications of such a course to their logical conclusion.

The most emphatic repudiation of the idea of a general strike came from the Dutch and German parties. Experience, so far, declared, Vliegen, is strongly against a general strike. 'It is not a means—let alone the only possible means—for securing the aims of the working class.' And Robert Schmidt said, to the enthusiastic applause of the German delegation, that for the German unions with their 900,000 members the question of a general strike was not even 'discussible'. 'The struggle of the proletariat for political and economic power,' he added, 'will not be determined by a general strike but by steady, uninterrupted work in all spheres of political and economic life.'

Support for Briand's resolution came from Jaurès's group and the Allemanists. The French Guesdists voted against, but the Russian Social Revolutionaries and the delegates from Switzerland and Japan also voted in favour. The resolution submitted by the commission was adopted by thirty-six votes to four.

No sooner, however, had the Amsterdam Congress risen than Italy experienced a mass political strike which was fiercer and more extensive than any previously known in her decidedly turbulent history. The impetus came from Sicily, where strikes had touched off unrest in many parts of the island, while in Buggaru and Castelluzzi police opened fire on mass demonstrations. When, on 15 September 1904, news of the bloodshed reached the north, the workers of Milan left the factories to demonstrate in the streets. Genoa, Monza, Rome and Leghorn were soon in the grip of strikes and the movement spread like a prairie fire across the whole country.

The signal for strike action had come from the Syndicalist wing of the party, led by Arturo Labriola, and immediately it broke out, the party's executive issued a manifesto declaring that the strike was the concern of the entire working class. The strike movement, however, had not been planned and it remained completely unorganized. An eyewitness, Oda Oldberg,[10] reported that the movement was 'so chaotic yet so overwhelming that it struck all those of us who lived through it as an elemental force which swept over us like an avalanche'. Both in extent and intensity this was indeed a 'total general strike', the first complete general strike in the history of the working-class struggle. It was a spontaneous explosion of class anger against gross injustice, a protest against the misuse of the state's armed forces in an industrial dispute. The workers had not forgotten the famous 'four days of Milan' in 1898, when the government of Antonio di Rudini had called out the army to destroy a mass demonstration against higher bread prices. Nearly 100 were killed and about 500 wounded when the troops opened fire. The working class in Milan was therefore the first to respond to the shootings in Sicily with sympathetic strike action. There was no immediate objective, apart from the implicit decision to stop future armed intervention by governments in industrial disputes. The Liberal Premier, Giolitti, was quick to promise this, as he had been emphatic in refusing to call out the troops,[11] and the strikers returned to work after a few days.

The Italian general strike of September 1904 was mainly a strike of unorganized workers. In spite of this it did not collapse, as Legien was convinced that such strikes must do. The question now was—what exactly had been achieved? The Syndicalists were confident that, in Arturo Labriola's phrase, it 'had proved to the masses that five minutes' direct action was worth as much as four years of empty parliamentary chatter'.[12] The Marxist leadership, led by Constantino Lazzari, saw the main achievement of the strike as being in its demonstration that, as Oda Oldberg wrote, 'the proletariat…in defence of its rights…could at any time call out the workers from the factories, mines and building-sites'.

However, the characteristic feature of the Italian general strike was the spontaneous reaction of the masses. They had not been 'called' away from work—they had leftefwfew of their own accord in a mood of profound resentment. The strike had not been declared, it had erupted as an expression of accumulated anger. It showed that the workers collectively—as individually—were subject to the law of action and reaction. They were 'brought to the boil and transformed into flood and movement only by actual events', as Lassalle had remarked in a letter to Marx in 1854 when, in a period of world-wide reaction, the workers had succumbed to a mood of profound apathy.

The law of action and reaction was manifested in spectacular fashion in the Russian revolution of 1905. This broke out a mere five months after the end of the Amsterdam Congress, at which Vliegen, for the Dutch delegation, had rejected out of hand the idea of a general strike, while Robert Schmidt insisted that the question was 'simply not discussible' by the German trade unions. Now Russia presented the imposing spectacle of 'Bloody Sundy', where things were truly 'brought to the boil' with the frightful slaughter of 22 January. After the massacre of unarmed workers, the muted anger of leaderless and unorganized masses built up into tremendous waves which dashed themselves again and again in the form of mass strikes against the structure of Tsarism, until that very stronghold of absolutism began to crumble under the pressure.[13]

It was an unforgettable experience, this first revolutionary uprising of the workers since the Paris Commune of 1871, and, for many contemporaries, the first experience of revolution. To some it seemed that they were living through a turning-point in world history and witnessing the start of a new epoch of European revolutions.[14]

These developments brought the problem of mass political strikes back on the agenda of European Socialist parties. Of particular importance was the volte-face in the German party in view of its commanding strength and prestige in the International. It was with reluctance that the German delegates had brought themselves, at the Amsterdam Congress, to vote for the resolution which recognized the mass political strike as a legitimate means, in extreme circumstances, of defending working-class rights. The conference which the party held at Bremen, soon after the Amsterdam Congress, had again refused a suggestion that the mass political strike and its relevance to the struggle of German Social Democracy should be put on the agenda for the forthcoming congress. And the Congress of German Trade Unions, meeting in Cologne at the end of May 1905, once again pronounced the general strike 'undiscussible' and 'hence all attempts to commit us to a particular line of tactics, through propagating the political mass strike, are objectionable'. Theodor Bomelberg, who supported the resolution in the name of the General Council, deprecated the Amsterdam decision to recognize the political mass strike in certain circumstances, declaring: 'We must emphatically put an end to this discussion in the German trade-union movement.'[15]

'Now it was impossible to stamp on further discussion. The excitement which spread from Russia to Germany and to the movement in all countries[16] inspired renewed debates on the problems of the mass political strike in the German party, its Press, its public meetings and at successive conferences—Jena in 1905, Mannheim in 1906, Magdeburg in 1910 and Jena in 1913.'

The problem was essentially whether the German workers could destroy, by legal means, the supremacy of the Junkers which had been maintained over many centuries, making use of the strength of Prussia, her monarchs, armies, bureaucracy, law courts and bourgeoisie. The centre of Junker power lay in the methods by which Prussia was ruled and particularly in the three-tier election system on which the entire régime in Germany rested. As long as the Junkers maintained this centre of privilege, there were strict limits to the development of German democracy and working-class power. Until the Prussian Landtag came to be elected by universal suffrage, Junker supremacy would remain untouched. But experience had shown that this was no wall of Jericho, to be thrown down by the blast of trumpets. Up till then, neither speeches, Press campaigns, public meetings nor even street demonstrations had had the slightest effect. The question now posed for the party was whether the political general strike would serve as an effective weapon in the fight for democracy in Prussia.

This debate turned at once on the political implications of a general strike. Bebel was convinced that there was no need for such a strike to develop into a revolution. If it occurred at all it should be regarded 'in every case as a method of peaceful struggle', he declared to the party conference at Mannheim. The majority view, however, voiced by Hilferding, was that if a political general strike were used by the strongest party in Germany against the strongest government and most closely-knit ruling class in the world, this would unquestionably precipitate a decisive struggle for power. 'In Germany,' he declared, 'a general strike, however it starts, must be prepared to meet the most powerful resistance.' In whatever way the party might present the issue—arising, for instance, out of the campaign for electoral reform in Prussia—'the ruling class will inevitably treat it as a question of survival'. The general strike in Germany was therefore a phase in a struggle which would have to be fought through to the finish, or end in disaster for the working class, 'because the enemy would interpret any general strike, however peaceful and legal, as a challenge to its supremacy and as an indication that its own existence was now at stake. It would therefore meet it with every means at its disposal.'[17]

It was this reason—the fact that a political general strike would inevitably become a struggle for the survival of the Socialist movement itself—which made every such discussion the occasion for deep uneasiness in the party and, even more, the trade-union leadership. In the course of half a century the German Labour movement had developed many characteristics of a state-within-a-state. It had won the support of over a third of the electorate. Bebel had become a symbol of the new status of German labour, with a large part of the population regarding him as a kind of 'Counter-Emperor'. He stood at the summit of the largest political party in the world, allied with the world's strongest trade-union movement.[17] Moreover, the German Socialist movement had developed its own elaborate bureaucratic superstructure. Its assets ran into millions, and it controlled a huge number of subsidiary organizations. It owned vast newspapers and publishing houses and great printing works. It had innumerable offices and halls and was often involved in adminstering building societies and both consumers' and producers' co-operatives. A staff of thousands of secretaries, editors, employees, workers and officials was required to operate this huge Labour movement and administer its manifold enterprises.[19] Together with this enormous growth, the movement had acquired a considerable influence in the state and society. The vast bureaucratic organizations had spawned their own political and trade-union élites among the party members, M.P.s, district representatives, local administrators and trade-union general secretaries.

The movement, in fact, had developed its own 'apparatus', obeying its own laws of growth and self-preservation, and members came to regard the movements as an end in itself. Such an apparatus, though originallyc reated to serve the needs of the movement, had by this time produced its own vested interests and its own conservative caste of mind. Concern for the movement's safety and its possibilities of normal development had its own effect on the minds of its responsible officials. The Labour movement had originally created its organization to prepare for social revolution, to sap, undermine and eventually destroy the existing class society. But with the growing strength and influence of its organization, the movement had lost its revolutionary dynamic. The stronger the organization, the more it stood to lose in a decisive struggle for state power. Everything which the working class had created through decades of considerable sacrifice could be lost in a few days or weeks of revolutionary conflict. Admittedly, the organization's existence might be threatened on the initiative of the ruling class itself, but in the depths of its heart the movement hoped that this might somehow be avoided. The stronger the party became, the greater was its popular following and the more dazzling were its electoral successes; and the larger its parliamentary representation, the smaller, it seemed to the leadership, was the danger of the rulers provoking a fight. The party leadership, and above all the top leadership in the unions, was especially concerned not to provoke one. It often recalled the warning of Friedrich Engels, in his well-known introduction writtenin 1895, to Marx's Class Struggles in France, not 'to let ourselves be driven into street fighting'. The growth of the party 'into the decisive power in the land, before which all other powers will have to bow' was, he believed, irresistible. 'We are thriving,' he added, 'far better on legal methods than on illegal methods and revolt. And there is only one means by which the steady rise of the Socialist fighting forces in Germany could be momentarily halted, and even thrown back for some time: a clash on a big scale with the military, a bloodbath like that of 1871 in Paris.' This was precisely what the leadership of the party and the unions feared—a 'clash on a big scale' with the power of the state. Hence their reluctance to give serious thought to the political general strike. German Social Democracy, revolutionary in its social aims, was by no means revolutionary in its methods of struggle.

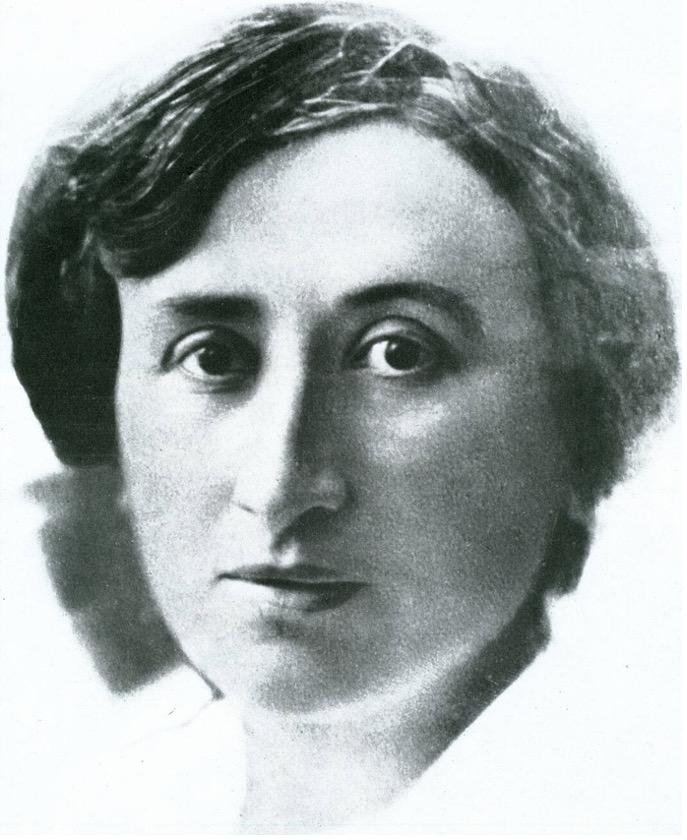

The idea of the political general strike as an offensive weapon in the struggle for an equal franchise in elections for the government of Prussia, was supported not only by the Marxist Left—Rosa Luxemburg and her group—but also, more surprisingly, by a section of the Revisionists, led by Eduard Bernstein, Friedrich Stampfer and Kurt Eisner. The overwhelming majority of the party rejected this view of the general strike, tending to agree with the 'Marxists of the centre', represented by Bebel and Kautsky, who acknowledged the general strike only as a defensive weapon—'as one of the most effective means of resisting…an attack on the general, equal and direct parliamentary suffrage or the right of assembly'—according to a resolution passed by the Jena Party Conference in 1905. It needed all Bebel's moral authority and diplomatic ingenuity to reconcile the unions to even this tepid endorsement of the political general strike.

While the Syndicalist wing of the Labour movement in France and Italy saw the general strike as a weapon of revolutionary attack, it was not destined to be used during the period of the Second International. In both countries, as in Germany, official Socialism saw it essentially as a defensive tactic. In Russia, the Social Democratic party still clung to the political general strike as a weapon of revolutionary attack, despite its failure to halt the counter-revolution which followed soon after the successful revolutionary outbreaks of 1905.

In Finland, the Social Democratic party called a general strike in support of its demand for universal suffrage and a free Press. It lasted from 30 October to 6 November 1905, and was called off only when a manifesto by the Tsar (Finland then being an autonomous part of the Russian Empire) promised a Parliament elected by universal suffrage and the ending of Press censorship. While it lasted, the strike had been almost total. The country had been virtually governed by a central strike committee, with sections responsible for the railways, commerce and industry and the police. The new franchise law became effective only after another year (on 1 October 1906), and then only under the threat of a new general strike.[20]

Three more parties resorted to general strikes during the last ten years of the Second International—the Austrian in November 1905, in a one-day demonstration strike for universal suffrage; the Italian in September 1911, in a twenty-four-hour protest strike against the war in Tripoli, and again in June 1914 in a monumental effort to preserve European peace; and the Belgian in April 1913, as part of the campaign against plural voting, which was called off in a few days when the government undertook to revise the constitution.

In Sweden it was the trade unions, not the Social Democratic party, which made use of the weapon of the general strike in 1909 in a counter-attack against an offensive of the well-organized big industrialists. A severe economic depression, which had already set in in 1907, brought about widespread unemployment. Wages were cut and industrial relations grew rapidly worse.

The trade unions attempted to resist and strikes flared up in a number of trades. The central organization of the employers demanded that the strikes should be called off and threatened a general lock-out. The unions decided, however, to resist. Instead of waiting to be locked out, they declared a general strike.

The strike was a trial of strength between the working and the capitalist class. It lasted a month. It was supported with considerable contributions by the trade unions in Denmark and Norway and a number of other countries. But at the end of a month funds were running out, and the strike committee was forced to order back to work those groups who had struck in sympathy with those directly involved. But the ultimate defeat was unavoidable since there was no question of turning the strike into a revolution.

The defeat greatly reduced the numerical strength of the party as well as of the trade unions. The party, which of course had put all its resources into the battle, lost half its members, their number decreasing from 112,000 in 1905 to 55,000 in 1910; and the trade unions lost more than 100,000, their membership falling from 186,000 to 80,000.

But the movement soon recovered, and in the first elections under the new Constitution in 1911, the Social Democratic party doubled its representation in the lower chamber, securing the election of 64 Socialists against 101 Liberals plus 65 members of the right-wing parties.

In all these instances of mass struggles, either with political or industrial objectives, the Socialist parties as well as the trade unions involved were anxious to keep the general strike as a purely legal instrument, to keep the struggle strictly within the bounds of legality and to avoid its being suddenly transformed into a revolutionary operation.

While the International was grappling in this way with the role of the general strike in the broader political movement, it was faced simultaneously with the far-reaching problem of the international general strike as a possible means of averting war. We shall return to this in a later chapter.

1. At the time of the Chartist petition of 1842, the population was under nineteen million, of whom eight million lived in towns. The 3,300,00 signatures represented over half of the adult urban population.

2. Max Beer, Geschichte des Sozialismus in England (Stuttgart, 1913), p. 262, and the chapters following.

3. For an account of which see below, in Chapter 21, 'The International and the War'.

4. 'Direct action' was elevated by the Syndicalists to the status of a 'moral principle which, in contrast to the tactics of discussion attempts to reach a basis of common understanding with the powers-that-be and the representative system, and has the power of raising the standard of life of the worker in addition to promoting the emancipation of the entire working class from capitalism and centralized control, by means of the opposite principle of direct self-help'—Erich Mühsam, 'Die direkte Aktion im Befreiungskampfe der Arbeiterschaft', in Generalstreik, monthly supplement to the Freier Arbeiter, vol. I (October 1905).

5. The social aim of the Syndicalists was formulated at the trade-union congress of 1906, in the famous Charter of Amiens, as follows: 'The trade union, which is today a fighting organization, will in the future be an organization for the production and distribution [of goods] and the basis of social renovation'. See Val R. Lorwin, The French Labor Movement (Harvard, 1954), p. 30; see also Eugen Naef, Zur Geschichte des französischen Syndikalismus (Zurich, 1953); J. Paul Wirz, Der revolutionäre Syndikalismus in Frankreich (Zurich, 1931); also Edouard Dolléans, Histoire du mouvement ouvrier (Paris, 1948), vol. II: 1871–1936. Dolléans had himself been active in the revolutionary Syndicalist movement.

6. The general strike is, he stated, 'the myth in which Socialism is wholly comprised, i.e. a body of images capable of evoking instinctively all the sentiments which correspond to the different manifestations of the war undertaken by Socialism against modern society. Strikes have engendered in the proletariat the noblest, deepest, and most moving sentiments that they possess; the general strike groups them all in a co-ordinated picture, and, by bringing them together, gives to each one of them its maximum of intensity; appealing to their painful memories of particular conflicts, it colours with an intense life all the details of the composition presented to consciousness. We thus obtain that intuition of Socialism which language cannot give us with perfect clearness.…'—Georges Sorel, Reflections on Violence, with an Introduction by Edward A. Shils (Glencoe-Illinois, 1950), p. 145. See also Richard Humphrey, Georges Sorel. Prophet without Honor (Cambridge, Mass., 1951).

7. Quoted in Louis Levine (Lorwin), 'The Labour Movement in France', in Studies in History, Economics and Public Law (vol. XLVI, 1912), pp. 89–90.

8. Protokoll, op. cit., p. 32. Briand also presented the case for the general strike at the Amsterdam Congress of the International in 1904. Two years later he was expelled from the party for entering the Clemenceau government in defiance of its decision. In 1910 he became Prime Minister and suppressed a railway strike in the same year. He ordered troops to occupy the railway stations, called up the strikers into the reserve and then forced them back to work under military orders.

9. See Jules Messine, Émile Vandervelde (Hamburg, 1948), p. 67. See also Émile Vandervelde, 'Die Belgischen Wahlrechtskämpfe 1902', in Sozialistische Monatshefte (1902) and La Parti ouvrier belge 1885–1925 (Brussels, 1925).

10. Die Neue Zeit, vol. XXIII, Part I (1904).

11. Believing that the strike would weaken the popularity of the Socialists, Giolitti dissolved Parliament soon after the outbreak. The party did, in fact, suffer a set-back in the new elections, with its representation reduced from thirty-three to twenty-seven.

12. See William Salomone, Italian Democracy in the Making (Philadelphia, 1945), p. 51.

13. A masterly account of the psychological processes at work can be found in Leon Trotsky, Die russische Revolution 1905 (Berlin, 1923), pp. 63–96. For an analysis of the strikes in Russia, see Rosa Luxemburg, Massenstreik, Partei und Gewerkschaften (Hamburg, 1906).

14. Characteristic of the impact of the Russian revolution on the minds of European Socialists is the response to it of Victor Adler, one of the most coolheaded leaders of the International. In a letter to Bebel on 26 December 1904, a week after the outbreak of the revolution, he wrote: '…to me, the centre of gravity lies now in Russia. I simply burn of tension, and I believe that there our destiny will be, if not decided, in any case decisively influenced.…'—Victor Adler. Briefwechsel mit August Bebel und Karl Kautsky, op. cit., p. 445.

15. Karl Kautsky, Der politische Massenstreik (Berlin, 1914), p. 117. The book gives a complete account of the discussion on mass strikes in the German Social Democratic movement. See also Elsbeth Georgi, Theorie und Praxis des Generalstreiks in der modernen Arbeiterbewegung (Jena, 1908).

16. Evidence of the profound effect of the Russian revolution can be found in the Protokoll des Parteitages der Sozialdemokratischen Arbeiter-Partei Österreich-Wien, 1905. In the course of a speech by Wilhelm Ellenbogen the report describes how: 'Comrade Nemee had just handed up a telegram, which had been brought in from the office, to the speaker on the platform. Soon the delegates at the front tables were whispering of "News from Russia". The silence in which Ellenbogen's speech had been heard now gave place to an excited hum of conversation. Ellenbogen suddenly interrupted his speech and began to read the manifesto of the Tsar in a voice trembling with emotion. In no time there was complete silence. But as soon as the first paragraph of the manifesto had been read out, ending with the promise of freedom of the Press and assembly, a deafening cheer broke out in the hall and galleries. "Cheers for the Russian Revolution! Hurrah for the Revolution!" When Ellenbogen resumed reading the telegram the delegates began to stand—it seemed appropriate to stand up on such an historic occasion. The Conference was gripped by an almost religious emotion. As Ellenbogen reached the concluding words of the Tsar's manifesto…the delegates instinctively found the appropriate way of expressing their feelings. Suddenly the hall rang out with the sound of revolutionary songs. The Czechs and Poles were singing the Red Flag, whereupon the Germans responded with the Marseillaise. Under the impact of the news the Party Conference decided to call on the workers to down tools on the day Parliament reassembled—28 November—and demonstrate in public meetings for the right to vote. In Vienna 250,000 men and women marched that day along the Ringstrasse to the Parliament building.' For the influence of the Russian revolution on German Social Democracy, see also the excellent study by Carl E. Schorske, 'German Social Democracy, 1905–1917', in Harvard Historical Studies, vol. LXV (1955).

17. Kautsky, op. cit., pp. 161 and 123.

18. The following figures show the strength of German trade unionism within the European Labour movement (Tenth International Report of the Trade Union Movement, 1912).

19. The free trade unions alone had a combined annual income of 70 million marks, with assets, in 1914, totalling 80 million marks. See Friedrich Stampfer, Die vierzehn Jahre der ersten deutschen Republik (Hamburg, 1947), p. 12. The party had sixty-two printing works, and ninety daily papers with a total circulation of 1,465,212; 10,320 people worked in its publishing house alone. See 'Bericht des Parteivorstandes an den Parteitag zu Jena 1913', in Protokoll über die Verhandlungen des Parteitages der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands (Berlin, 1913), pp. 28–9.

20. For a detailed account of this struggle for the franchise, see the Report from the Social Democratic party of Finland to the International Socialist Congress at Stuttfart, in Die Sozialistische Arbeiter-Internationale (Berlin, 1907), pp. 191–3. In the course of the campaign, the membership of the Party increased from 16,610 organized in 99 branches at the end of 1904, to 45,298 in 177 branches at the end of 1905, and to 85,027 in 937 branches by the end of 1906. See N. R. af Ursin and Karl H. Wilk, 'Die Arbeiterbewegung in Finland', in Archiv für die Geschichte des Sozialismus und der Arbeiterbewegung, ed. Carl Grünberg, vol. XII (1926), p. 46.