From the beginning, many writers compared Socialism with Christianity in the days of the early church, before it became established as a state religion. They saw, in Socialism, a new gospel of salvation, and in the Labour leaders the apostles of a new teaching, possessing the same boundless assurance of ultimate success as had fortified the early Christians during the first three centuries of their existence. If one is to make such a comparison, the Second International can be taken as the apostolic period of Socialism, the time of preaching and propagation, preceding the assumption of political power.

In the period of the Second International, Socialism assumed the character of a mass movement. Unlike the First International, which was formed in most countries by none too stable groups of individual members, the Second was based, within a few years of its foundation, on organized mass parties. Their conception of Socialism was, in a general sense, Marxist, though Marxism was by no means the only significant trend. Even after the expulsion of the Anarchists there were revisionists, reformists and working-class radicals who represented powerful conflicting tendencies. But Marxism was, without doubt, the dominant school of thought, and most parties of the Second International had no hesitation in describing themselves as Marxist. In the International's basic statement of principles there were all the leading ideas of Marx, his philosophy of history, his theories of economics, and his attitude to the class struggle, the state and revolution. In its ideology, therefore, the Second International was revolutionary, and its aims included not only a radical transformation of society but a clear view of revolution as the 'midwife of history', the inevitable culminating stage in the struggle to free mankind from capitalism and class rule.

At its foundation, the spirit of the Second International was one of buoyant optimism. The collapse of the capitalist system and the irresistible advance of the new, victorious Socialist society seemed equally inevitable in the fairly near future. At the Erfurt Congress of the German Social Democratic party in 1891, only two years after the revival of the International, August Bebel told his fellow delegates: 'I am convinced that the fulfilment of our aims is so close, that there are few in this hall who will not live to see the day.'[1] It was this confidence of imminent victory which gave the Socialist movement its extraordinary enthusiasm during the period of the Second International.

But this optimism carried the seeds of tragedy. In the twenty-five-year history of the Second International, the Socialist movement became established as a force. In 1914, on the eve of the First World War, membership of Socialist parties, and of trade unions closely connected with them, ran into hundreds of thousands, while in parliamentary elections they numbered their votes, in some countries, by the million. The surprisingly rapid growth of the movement gave rise, in the minds of its supporters, to a fatal over-estimation of the power of Socialism which bore little relation to reality. They chose to overlook the fact that the idea of Socialism had penetrated ot only a small section of the working class and that the Socialist parties, in all countries where they existed, were faced with the hostility of an overwhelming majority of the population. They underestimated the power of conservative and nationalist traditions and overestimated the extent to which the revolutionary notion of international working-class solidarity had been accepted, even among the working class. They saw in the International a force capable of averting the threatening war between the Great Powers. They saw, in Social Democracy, a means of arousing revolutionary resistance to war. The Second International was destined to be destroyed by the failure of these hopes and the disillusionment which followed.

Optimistic expectations about the historical destiny awaiting them were already pronounced in the Addresses which were read at the opening of the foundation congress,[2] which met in Paris on 14 July 1889—the centenary of the storming of the Bastille. The Salle Petrelle, where the congress took place, was festooned with red cloth, reinforced by red flags. Above the rostrum, in gold letters, shone the closing words of the Communist Manifesto, 'Working Men of All Countries, Unite!' An inscription in the foreground announced the central aim in the fight for working-class emancipation: 'Political and Economic Expropriation of the Capitalist Class—Nationalization of the Means of Production'.

The congress was the guest of the Parti Ouvrier Français, the Blanquist Comité Révolutionaire Central and of the Fédération Nationale des Syndicats Ouvriers de France, the main organization of the French trade unions. The spirit of the French party was admirably expressed on a poster at the rostrum with which they greeted the congress: 'In the name of the Paris of June 1848, and of March, April and May 1871, of the France of Babeuf, Blanqui and Varlin, greetings to the Socialist workers of both worlds.' After the congress was over the delegates organized a march in honour of the revolutionary pioneers. An enormous wreath of everlasting flowers was carried by sixteen men to the grave of the Communards in the Père Lachaise cemetery, and to the grave of Blanqui. The German delegates also marched to the graves of Heinrich Heine and Ludwig Börne in honour, as Liebknecht said in a public oration, 'of the martyrs of freedom and international fellowship'. Paul Lafargue welcomed the delegates, in the name of the Paris organization, as 'apostles of a new idea'. Édouard Vaillant, who together with Wilhelm Liebknecht had been elected president on the first day of the congress, described the congress as 'the first parliament of the international working class', which had assembled, he declared, to conclude a 'sacred alliance of the international proletariat'.

The origin of the Second International was more prosaic than the high-flown speeches with which its inaugural congress opened. After the failure of the efforts to revive the old, comprehensive International at the congress of Ghent in 1877 and that of Chur in 1881, the party of the Possibilists, led by Paul Brousse, had organized two international working-class congresses in Paris in 1883 and 1886. The Possibilists had themselves broken away from the Fédération du Parti des Travailleurs Socialistes, set up in 1880, the programme of which, under the influence of Jules Guesde and Paul Lafargue, had been uncompromisingly Marxist. In opposition to the Guesdists, the Possibilists were committed to an evolutionary Socialism which would be secured through aiming at modest, realizable reforms in alliance with the radical wing of the bourgeoisie.

The Guesdists, at loggerheads with the Possibilists from the beginning, boycotted the congresses called by their rivals. Both these congresses, however, had been attended by representatives of the British Trades Union Congress (T.U.C.), the leading organization of the British trade unions, whose leaders were themselves in alliance with the Liberal party. The T.U.C. then decided to call an international workers' congress of its own in London in 1888. But representation was limited mainly to trade-union organizations. Socialist parties, such as the German and Austrian, and the two British Socialist bodies, the Social Democratic Federation and the Socialist League, were consequently excluded, and the representatives of the Socialist parties of France, Belgium, Holland and Denmark, who arrived at the congress, were admitted as delegates of their respective trade-union movements, and not of their parties. The congress decided to meet again in the following year, and asked the French Possibilists to arrange for the meeting to be held in Paris.

The Paris Congress, like the London one, was clearly intended for trade unionists and meant to exclude representatives of political parties. The Possibilists, however, invited all the Socialist parties to attend, alongside the trade unions, upon which the Guesdists convened an international congress of their own. To avoid the rather unedifying spectacle of two rival working-class congresses meeting at the same time, the German party tried to persuade the Possibilists and Guesdists to combine their forces. It invited both wings of French Socialism to a conference in The Hague at the end of February 1889, but the Possibilists decided to abstain. The delegates attending in The Hague then decided to call, in their own name, an international congress in Paris for July of the same year, which would have, as the first item on its agenda, the question of bringing the two congresses together.

In this way, two congresses assembled in Paris on 14 July 1889: the Possibilists in the rue Lancre, the Marxists in the rue Petrelle. Though the Possibilist congress, with its 600 delegates, was numerically stronger than the Marxist, with 400, it was the less important of the two and was the last international congress to be held under Possibilist auspices. It was the congress in the rue Petrelle which went down in history as inaugurating the Second International.

It should be said at once that the congress in the rue Petrelle, as soon as it had officially opened, devoted its first two days to a debate on ways of unifying the rival congresses. On a motion by Liebknecht, it delegated Andrea Costa and Amilcare Cipriani to negotiate a unity agreement with the Possibilists. The latter, however, insisted on checking the mandates of the delegates, a gesture reasonably described by Costa as 'an act of mistrust' which caused the negotiations to be broken off.

In spite of this uncompromising background, the inaugural congress of the Second International succeeded in uniting representatives of the Socialist and Labour movements in 'both halves of the world'. The French delegation was, naturally, the strongest. It comprised 221 members, including the Blanquist, Édouard Vaillant, who had been a member of the Paris Commune in 1871; the Marxists, Jules Guesde, Charles Longuet and Paul Lafargue, the latter two being sons-in-law of Marx; and Sébastian Faure, representing the Anarchists.

Despite the Anti-Socialist Law, there were eighty-one delegates from Germany, including Wilhelm Liebknecht, Karl Legien, architect of the German trade-union movement, Eduard Bernstein, Georg Heinrich von Vollmar, Hermann Molkenbuhr, Clara Zetkin and Wilhelm Pfannkuch. The German delegation had been elected directly by the workers, partly at 125 public meetings and partly, where such meetings had been prevented by the police, through voting papers passed round the factories and workshops. Interest in the balloting was, according to Vollmar, hardly less than at a normal parliamentary election.

The next strongest delegation, numbering twenty-two members, was the British. It was led by the leading Socialists in the country, including Keir Hardie, founder of the Scottish Labour party and representative of the 56,000 Scottish miners; William Morris, already a celebrated poet and craftsman and founder of the Socialist League; R. B. Cunninghame Graham, great-great grandson of the Earl of Menteith, related to the Stuarts and the first Socialist to sit in a British Parliament; Eleanor Marx-Aveling, Marx's youngest daughter and a well-known speaker in the East End of London; and John Burns, a revolutionary trade-union leader who went over to the Liberals in the 1890s and, later, became a Minister—the first worker to sit in a British Cabinet. Only H. M. Hyndmann, founder of the Social Democratic Federation, was missing; a rival of William Morris, he attended, despite his strongly Marxist views, the rival Possibilist congress in the same city.

The fourteen delegates from Belgium included the now grey-haired César de Paepe, one of the leading figures in the First International, Édouard Anseele, architect of the Belgian co-operative movement, and John Volders, the party organizer. Italy was represented by twelve delegates, among them the two already mentioned—Andrea Costa and Amilcare Cipriani from the First International—and the Anarchist Saverio Merlino. From Austria there was Victor Adler, leading a delegation of eleven.

Working-class parties in Holland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Switzerland, Hungary, Bohemia, Poland, Russia, Romania, Bulgaria, Spain, Portugal, the U.S.A. and Argentina were represented by smaller delegations. Some of them, as, for example, the Argentinian delegation, represented the only existing Socialist group or, as in the case of the Russian and Polish delegations, the only groups of Socialist refugees abroad. Of the five members of the United States delegation, one only represented the Socialist Workers' party, one was a delegate from the 'United Brotherhood' in Iowa, while three were from Jewish trade unions in New York. Admittedly, the congress also received a message of sympathy from the American Federation of Labor, the main organization of trade unionists in the United States, signed by Samuel Gompers. The delegations also included individuals of some historical importance in the international Socialist movement. We have already mentioned a number from France, Germany, Belgium, Austria and Italy Among the others were such leading figures as G. V. Plekhanov and Peter Lavrov, the leading theorists of each of the two streams of Russian Socialism; Felix Daszynsky, leader of the Polish Socialists in Austria; Pablo Iglesias, founder of the Spanish Socialist party; Domela Nieuwenhuis, a celebrated figure in the Dutch Socialist movement; and Wilhelm Hubert Vilegen, architect of the Socialist party in Holland.

The main theme on the agenda was the question of international labour legislation. But before this item was reached, congress heard reports from the various delegations on the struggle, setbacks and achievements of the Labour movement in their respective countries. These reports gave a useful and comprehensive picture of the strength of the international working-class movement at the time of the International's revival.

The German Socialist party was already the strongest, and it remained so throughout the life of the Second International. At the Gotha Congress, in 1875, both the Marxist and the Lassallean sections of the movement had come together to form a united party. Three years later it was confronted with the Anti-Socialist Law contrived by Bismarck to bring about its destruction. And, in fact, the legislation imposed heavy losses on the party. During the twelve years in which it was in force, 332 labour organizations were dissolved, 1,300 newspapers and periodicals suppressed, about 900 party activists driven from their homes and 1,500 sentenced to a total of 1,000 years' imprisonment.[3] The growth of the party in the face of such severe repression was all the more impressive. In 1881, in the elections for the German Parliament which followed the passing of the Anti-Socialist Law, the party received 310,000 votes. Three years later the figure was 550,000, and by 1887 it had grown to 763,000. At the elections of 1890, after the Anti-Socialist Law had expired, the party more than doubled its previous vote, with a total of 1,427,000, about a fifth of all votes cast. Thirty-five Socialist members were returned to the German Parliament. At the same time, the party Press had grown to nineteen daily papers and forty-one weeklies, while the number of trade unionists had reached 120,000.

In Britain, the trade-union movement was naturally much stronger and more influential than in Germany. Keir Hardie, in his report to the foundation congress, claimed that of the ten million industrial workers in his country, about a million belonged to trade unions. But the British trade unions were far from being Socialist. Indeed, most of their leaders saw in Socialism merely a utopia, and in the theory of the class struggle a dangerously destructive doctrine. They believed firmly in an ultimate 'harmony of class interests'. Their main concern was to secure, through parliamentary pressure, reforms in trade-union legislation, and in 1871 the T.U.C. established a Parliamentary Committee to organize this pressure and to strengthen the influence of Labour in the House of Commons. They fought elections, however, in alliance with the Liberal party, and the working-class members of Parliament—eleven were elected in 1886 and fifteen in 1892—formed a section of the Parliamentary Liberal party. Only Keir Hardie, John Burns and Cunninghame Graham could be considered in any sense as independent workers' representatives.

However, the trade unions' alliance with the Liberal party proved quite incapable of protecting the workers from the disastrous consequences of the prolonged economic crisis of the 1870s and 1880s. Increasing numbers of unemployed voiced their protests at meetings, public demonstrations and hunger marches, and the agitation spread to the factories and mines, where the employers were trying to cut wages. Keir Hardie, John Burns and other leading trade unionists worked hard to break the alliance with the Liberals and to organize an independent workers' party which, freed from the Liberal party's commitment to capitalism, could represent working-class interests effectively. This radical mood of the workers was also reflected in intellectual circles, and H. M. Hyndman took the initiative in forming a new party, the Democratic Federation, in 1881.

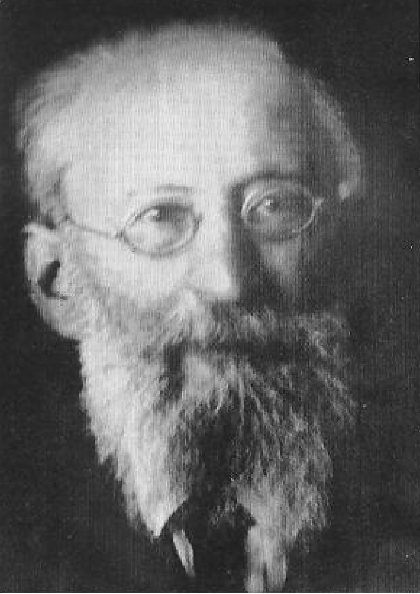

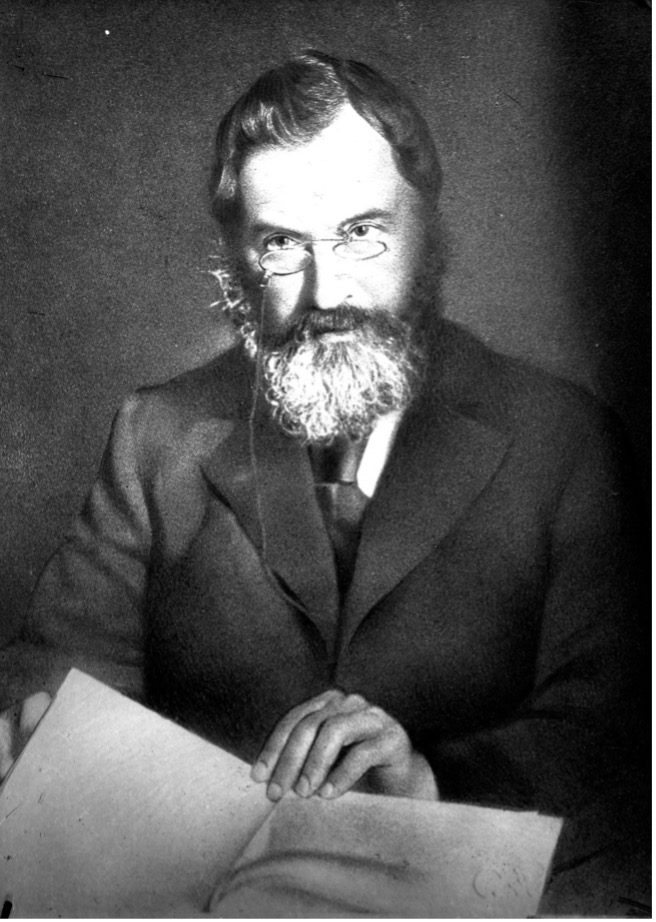

Henry Mayers Hyndman (1842–1921) was a prolific writer and a formidable public speaker, whose private means—his grandfather had made a substantial fortune out of the West Indian slave-trade—enabled him to indulge his intellectual and social interests freely, without having to concern himself with earning a living. The first volume of Das Kapital, which he read in 1879, transformed his whole outlook, and through frequent conversations with Marx he became an ardent convert to Socialism. In the year in which the Democratic Federation was founded he published England for All, a popularization of Marx's economic theories with particular reference to England. Two years later he published his Historical Basis of Socialism in Great Britain, a comprehensive study of the development of capitalism, the Labour movement and Socialism from the fifteenth to the late nineteenth century. His original aim in establishing the Democratic Federation was to revive the Chartist movement, in the traditions of Ernest Jones and Julian Harney, but three years later the Federation acquired a distinctively Marxian socialist outlook and changed its name to the Social Democratic Federation (S.D.F.).[4]

The S.D.F. began as a small body of Socialist intellectuals from the middle and working classes. Its members included William Morris, one of the most attractive figures in the history of British Socialism, and author of the famous utopian News From Nowhere, which became a classic of the movement. Other leading recruits were Ernèst Belfort Bax, a scholar and writer; Henry H. Champion, the son of a major-general and, like his father, an army officer who, however, resigned his commission in protest against Britain's imperialist war on Egypt; Andreas Scheu, one of the leaders of the Austrian Socialist movement, who had emigrated to England after its split in 1874; J. L. Joynes, a master at Eton and a poet who had translated Herwegh and Freiligrath into English; Walter Crane, whose engravings symbolizing the workers' struggle were reproduced in countless left-wing publications in many countries for several generations; Annie Besant, who later emigrated to India and earned an honoured place in the annals of the Indian nationalist movement; Eleanor Marx-Aveling; and the trade-union leaders, John Burns, Ben Tillett, Tom Mann and Harry Quelch, who started life as a cow herdsman, became a wage-earner, later a trade-union secretary and finally editor of Justice.

Justice was the first modern Socialist periodical in England. Appearing for the first time in January 1884 with the subtitle 'Organ of Social Democracy', it soon became the Federation's most important medium of propaganda. It was started with a capital of £300, contributed by the Socialist poet Edward Carpenter. Edited by Hyndman and, later, by Quelch, it included William Morris, Belfort Bax and Andreas Scheu among its contributors. The Federation published pamphlets, such as Socialism Made Plain, which sold 100,000 copies, and evening after evening its members spoke at street-corner and factory meetings. The Federation soon increased its support, and by 1887 it had thirty branches, mainly in London and in the textile districts of Lancashire, but it never succeeded in becoming a mass organization.[5]

After less than a year the S.D.F. experienced its first serious split. Included in its ranks were Socialists of varying points of view, revolutionaries, anti-parliamentarians, reformists and Anarchists. The dictatorial and somewhat erratic leadership of Hyndman gave rise to increasing discontent. At the end of 1884 William Morris, Belfort Bax, Edward and Eleanor Marx-Aveling and others who were critical of Hyndman's personality and tactics left the Federation, together with most of the anti-parliamentarians and Anarchists, to form, under Morris's leadership, the rather ill-assorted Socialist League. A year later the League produced the first number of its organ, Commonweal, to which Engels became an occasional contributor. The League had even less success than the Federation in acquiring a mass membership, and when the Anarchists captured the leadership, William Morris, together with the remaining Socialist members, resigned in 1890. After that there was some rapprochement between Morris and the S.D.F. The Socialist League soon disintegrated.

At the beginning of 1884 another group of Socialist intellectuals, including the civil servant, Sidney Webb, and the playwright, Bernard Shaw, later to be joined by the novelist, H. G. Wells, formed the Fabian Society. Its declared aim was 'to persuade the English people to democratize completely its political constitution and to nationalize its industry, so that its material life will become completely independent of private capital'. The aim of the society was expressed even more clearly in its programme. The society aimed, it declared, 'at the reorganization of society by the emancipation of land and industrial capital from individual and class ownership, and the vesting of them in the community for the general benefit'.

The Fabians appealed not only to the workers but to all classes of society in their attempt 'to awaken the social conscience by bringing present miseries to the knowledge of society'. One of their chief methods was the production of pamphlets—many of them along lines similar to the first volume of Das Kapital, which, as the Fabians said, 'contains a tremendous amount of carefully checked and well-established facts about modern civilization'. These pamphlets—the famous Fabian Tracts—and leaflets were distributed in tens of thousands. Like the plays of Bernard Shaw and the social novels of H. G. Wells, they did a great deal to permeate the moral and intellectual atmosphere of Britain with Socialist ideas.

Although none of these bodies of Socialist intellectuals succeeded in attracting a large mass of support, their propaganda helped to create an atmosphere which favoured the spread of industrial militancy. This revived once again at the end of the 1880s as the economic crisis receded. There was a considerable fall in unemployment, unskilled workers began to join the unions in large numbers and there was a growing movement to establish an independent party of the working class. At the beginning of 1887 Keir Hardie founded The Miner. Changing its name, two years later, to the Labour Leader, this soon became one of the most influential Socialist journals in the field. In 1888 Henry Champion's paper The Labour Elector and Annie Besant's The Link were both started. All these new working-class papers contributed to the growing feeling against the policy of the existing trade-union leadership, for the ending of their alliance with the Liberals and the formation of an independent workers' party. None of the Labour leaders had grasped the need for such a party more clearly or advocated it more persistently than Keir Hardie, a pioneer of Socialism in Britain and a remarkable figure, in some ways reminiscent of the German leader, August Bebel.[6]

Keir Hardie (1856–1915) was born into a very poor working-class family, in Scotland. His father was a ship's joiner who had been incapacitated by an accident, so that the young Hardie had to go out to work as an errand boy at the age of eight. For a time the entire family of father, mother and two children had to live on the 4s. 6d. a week which the child was able to earn. As he could not attend school, Keir Hardie's mother taught him to read and write in the evenings. At the age of ten he began to work in the mines. His first job was that of 'trapper': he had to open and close the ventilation shaft, working for ten hours a day in gloomy solitude, the darkness relieved only by the flickering of his lamp. Encouraged by his mother, who came of farming stock, Keir Hardie acquired through persistence and his own native wit an exceptional knowledge of books. The sources of his Socialism lay in the spirit of democracy and freedom in the poems of Burns, Carlyle's social criticism, the Sermon on the Mount and the outbursts against oppression and injustice which he found in the Hebrew prophets. He despised demagogy and unlike his contemporary, John Burns, he had no particular gifts as a public speaker. His moral qualities, however, his disinterestedness and sincerity, won him the lasting affections of the Scottish miners. In 1879, when scarcely twenty-three, he was elected secretary of the Scottish Mineworkers' Union, and in January 1889 he founded the Scottish Labour party, one of the forerunners of the Independent Labour party, which was to become the first mass party of democratic Socialism in Britain.

The year 1889 was, indeed, the turning-point in British labour history, the most outstanding event of the year being the great London dock strike. At the beginning of the year the gas workers in the East End, by merely threatening to strike, had secured an immediate reduction of the working day from twelve to eight hours. This success encouraged the low-paid London dockers to press their wage demands. When these were rejected, 10,000 completely unorganized workers went on strike in August 1889, under the leadership of John Burns, Ben Tillett and Tom Mann. The strike lasted for five weeks, and turned into an impressive demonstration of working-class solidarity. There were no strike breakers, and the general public sympathized with the strike. Collections raised nearly £50,000 and Cardinal Manning offered to mediate. The strike ended with nearly all the demands of the workers being granted.[7]

The two victories of unskilled workers, coming within a few months of each other, gave tremendous impetus to the trade-union movement. The East End of London, that 'immense haunt of misery', had ceased, in Engels's words, to form a 'stagnant pool'. It had 'shaken off its torpid despair',[8] and seen the birth of a new type of trade union, catering specifically for the unskilled worker. During the year of the Second International's foundation in Paris, nearly 300,000 workers joined trade unions, and a further half million in the two years following. During this period, in which the cost of living rose by a little over 4 per cent, the Mineworkers' Union secured a wage-increase of over a third, while trade-union pressure generally raised wages by an average of 10 per cent.

In 1889 the leadership of the trade unions had passed, up to a point, into the hands of Socialists such as Keir Hardie, John Burns, Ben Tillett and Tom Mann. They hoped to establish a Labour party which would be class conscious, independent of the middle class and dominated by a Socialist outlook. On 13 January 1883, this party was set up at a conference in Bradford, with Keir Hardie in the chair. It called itself the Independent Labour party, more generally known as the I.L.P., the main point in its programme being the transfer of the means of production to public ownership. It expanded quickly. According to Keir Hardie, its membership, two years after its formation, exceeded 50,000.[9]

With the establishment of the I.L.P., Socialism for the first time secured a mass basis among the working class. In England, however, unlike continental countries, the Socialist movement did not become preoccupied with ideological disputes. Anarchism was quite foreign to the temperament and traditions of the British people, and from Marxism the English Socialists took only the economic objective of social ownership and control of the means of production. And although some leading intellectuals, such as Hyndman and his circle, expounded and were inspired by the whole range of Marxist ideas, the ideology as such never gained any great influence over the movement. The Socialist outlook which spread from the I.L.P. into the general Labour movement derived its inspiration from Christian ethics and the political traditions of British radicalism.[10]

In France, on the other hand, which has some claim to be considered the cradle of Socialism, the movement was split from the very beginning into rival ideological schools. When the movement began to recover from the disaster of the Paris Commune, its leaders were preoccupied with finding the correct theoretical basis. In 1879 the government granted an amnesty which restored freedom to ex-Communards, and in October of the same year a workers' congress assembled at Marseilles, founded the Fédération du Parti des Traveilleurs Socialistes. Jules Guesde, who had been largely responsible for founding the new party, became its first leader.[11]

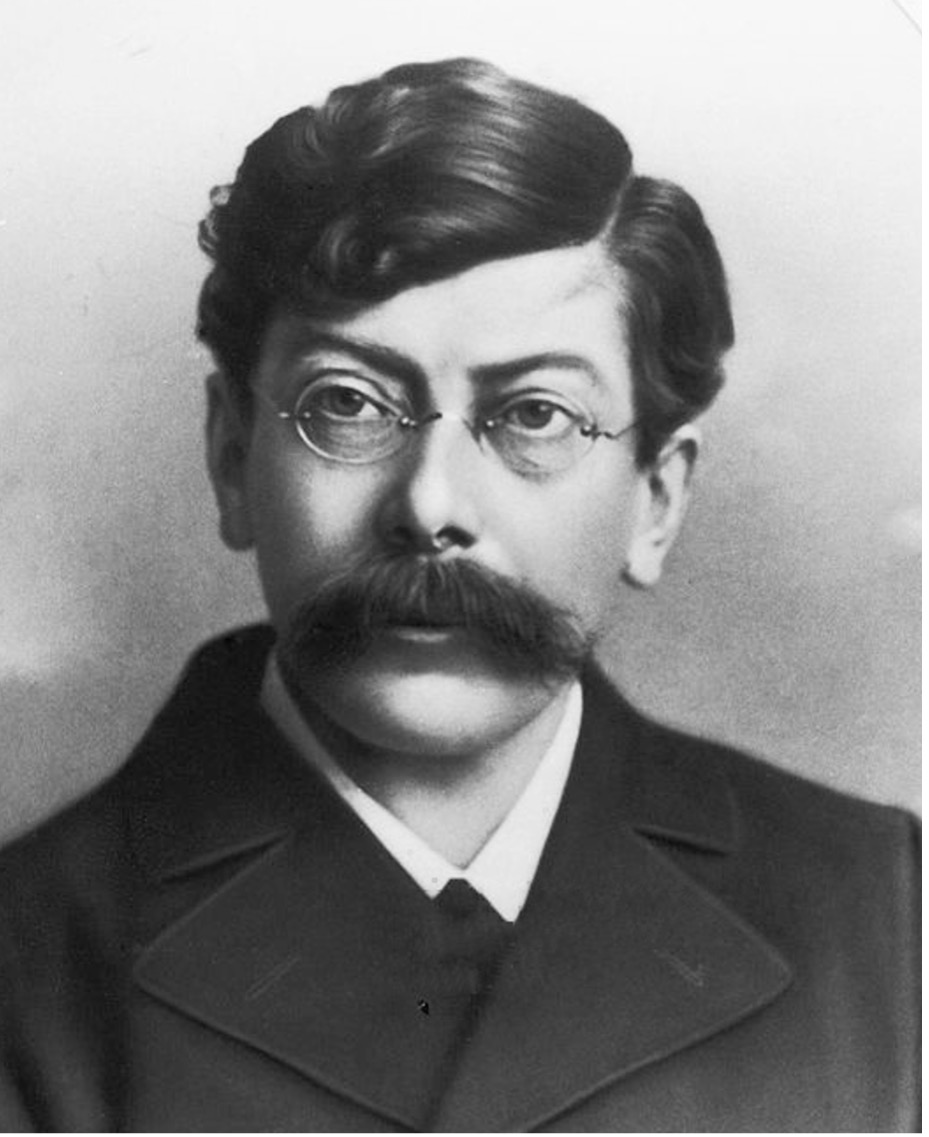

Jules Guesde (1845–1922) began his career as a radical-republican journalist. During the Commune he became a Socialist, and an article which he wrote in its defence earned him a prison sentence of five years, which he avoided only by escaping to Switzerland. From there he went to Italy, and returned to France in 1876. A year later he founded the Socialist weekly, Égalité, the first Marxist periodical in France, which included Wilhelm Liebknecht and César de Paepe among its contributors. The main object of Guesde's paper was the foundation, in France, of its own highly centralized party of Marxian Socialism, on the model of the German Social Democratic party, which he greatly admired. Under his leadership the Marseille Congress declared itself fundamentally opposed to the bourgeoisie, and in favour of the 'common ownership of land, mines, implements of production and raw materials'. After the congress, Guesde went, together with Paul Lafargue, to London to discuss the programme and constitution of the new party with Marx and Engels. Two documents, embodying their conclusions and drafted jointly by Guesde and Paul Lafargue, were embodied in a resolution adopted by the party's second congress in Paris in 1880.[12]

Only a year later, however, at the congress in Le Havre, the party suffered its first split. It contained within its ranks three incompatible groups. Besides the Marxists there were the followers of Proudhon, believers in Socialism through the development of co-operatives, who rejected both the theory of the class struggle and the desirability of political action. A third group were the Anarchists who, while agreeing with the Marxists in acknowledging the class struggle, opposed all forms of political activity, including parliamentary elections. Both anti-Marxist groups revolted against the party leadership and withdrew.

There was still another section, led by Paul Brousse (1854–1912), which opposed Guesde's theory of revolutionary Socialism by their own ideology of advancing to Socialism in gradual, evolutionary stages. Brousse, a doctor of medicine, had fled to Switzerland after the collapse of the Commune. There he met Bakunin, and worked for a time in the Anarchist Jura Federation. When the amnesty enabled him to return to France, he had become a reformist. However, he joined forces with Guesde and Lafargue, while arguing, in his journal, Le Prolétaire, for a theory of municipal Socialism, and for the nationalization of industry by city and provincial governments rather than, as in the Marxist version, by the state. He also advocated an alliance, including election agreements, with middle-class radicals, to secure the greatest possible representation of Socialists on public bodies through which social and political reforms could be implemented.

The party split once again at the congress in Saint-Étienne in 1882. This time it was on questions of theory and tactic. Brousse's supporters, who became known as the Possibilists, won a majority and secured control of the party. They changed its name to the Parti Ouvrier Socialiste Révolutionnaire—despite their decidedly anti-revolutionary views. Guesde and his followers formed the Parti Ouvrier Français, in close lisaison with the trade unions represented in the Fédération Nationale de Syndicats.[13]

It was not until 1884, when trade unions became legal, that they began to appear in strength on the French scene. Up to that time their activities had been curbed by the decree passed in the National Assembly in 1790 during the French Revolution, made even more severe by the Code Napoléon. The formation of trade unions had been punishable by law and they could be organized only under cover of friendly societies or clubs. 'Our bourgeoisie,' complained Guesde at the Congress of the International, 'are more heartless and ruthless than any other, as they showed only too clearly in the massacre of workers in June 1848 and May 1871. They ground the French working class to powder, smashed it to smithereens and, by suppressing trade unionism and freedom of association, deprived it of all possibility of common action.'[14]

Once trade unions had been legalized, they proceeded to establish a joint organization, the Fédération Nationale de Syndicats, which was founded at the Lyon Congress of trade unions in 1886. But within the trade-union movement two opposed factions contended for leadership. The anti-parliamentary faction advanced the policy of 'direct action', by which they meant the achievement of working-class power through the general strike, while those influenced by Proudhon rejected both the general strike and political struggle. Both factions were soon in public dispute with the Parti Ouvrier, whose programme called for political struggle by the working class, while rejecting the general strike as a piece of fantasy. These controversies played their part in splintering the Socialist movement still further. Within a few years the trade unions had completely dissociated themselves from the Socialist party.

Meanwhile, the Possibilists themselves had split. Jean Allemane, a Communard who had been deported to the penal colony of New Caledonia, had joined forces with Brousse on returning to France, but soon opposed him on the question of seeking alliances with middle-class parties. Allemane was also an advocate of the general strike as a keyweapon in working-class emancipation. In 1890 he and his supporters broke with the Possibilists and formed the Parti Ouvrier Socialiste Révolutionaire, whereupon the Possibilists dropped the word 'Révolutionaire' from the title.[15]

It should also be noted that the Blanquists, who had played a major part in the tragedy of the Commune, had reorganized themselves soon after the amnesty into the Parti Socialiste Révolutionaire, under the leadership of Vaillant. Reaction, in the period of triumph, had been quite unable to eradicate Blanquism, with its roots in the spirit of Babeuf and the traditions of the great French Revolution. The Blanquists still had a considerable following in Paris and in some of the provincial centres. They were closest to the Parti Ouvrier, but did not fuse with it completely until 1905. At the moment when the International revived, therefore, the French Socialists had disintegrated into six conflicting tendencies, struggling for leadership in the Labour movement—Broussists, Guesdists, Blanquists, Allemanists, Syndicalists and Anarchists.

However, in spite of the numerous schisms, the French Labour movement gained rapidly in influence. The Socialist vote rose from 30,000 in the first elections following the foundation of the party, to 179,000 in the elections following in 1889, and climbed to 440,000 in the 1893 elections.

The Belgian Labour movement, like nearly all such movements in the first phase of their development, went through a very similar process of internal conflict and splits, but it recovered more quickly than that in France. Soon after the end of the First International, in which the Belgian Federation, led by César de Paepe, had played an important role, its sections became convulsed in an ideological conflict between the Walloons, who tended to be influenced either by the Anarchists or by the Blanquists, and the Flemish, who were Social Democrats. In 1877 two separate parties appeared, the Socialist party, founded by Édouard Anseele and E. van Beveren, and the Brabant Socialist party among the Walloons. At the inaugural congress of the Belgian Labour party (Parti Socialiste Belge) in Brussels in April 1885, both parties amalgamated, and the split in Belgian Socialism was largely overcome.

Soon, however, there were fresh disagreements on the method by which the party should conduct its campaign for the franchise. A fighting pamphlet in favour of the workers' right to the vote, drafted by the Walloon Socialist, Alfred Defuisseaux, and called Le Catéchisme du people, sold the surprising number of 260,000 copies. In 1886 it provoked a great and largely spontaneous strike movement in the mining district of Charleroi. The strikes soon spread to Liège and along the Borinage. The government called out police and army against the strikers. 'For some days the province of Hainaut presented the dramatic spectacle of a full-scale war. Martial law was proclaimed in the towns, town halls were occupied by the army, soldiers were camped in the yards of factories and around the pit-heads, squadrons of cavalry patrolled the streets. The shots of the soldiers…put down the workers' rising in terror': in these terms the historian Henri Pirenne described the situation in the strike-bound areas.[16] After the failure of the general strike the leaders were prosecuted, some being sentenced to twenty years' solitary confinement. Anseele was given six months in prison for asking mothers of the soldiers to implore their sons not to fire on the workers.

Disappointment at the defeat of the strike combined with disgust at the sentences to bring about renewed struggle between the Blanquist and Social Democratic wings of the party. Led by the brother and the son of Alfred Defuisseaux—Léon and Georges—a new party was formed in 1887, calling itself the Republican Socialist party. It began at once to work vigorously for a general strike and a revolutionary uprising of the workers. But the mass strike which it succeeded in starting at the end of 1888 was also abandoned in failure. This paved the way for a reunification of the two wings at the Louvain Congress in 1889. The conflict of views on the general strike as a weapon in the class struggle was settled at the Namur Congress in April 1892 by a resolution recognizing it as a legitimate instrument in the struggle for the franchise. A few weeks later the party duly called a general strike in the cause of electoral reform. Hundreds of thousands responded to the strike call, and once more there were bloody clashes between the workers and the armed might of the state. The general strike, which had broken out on 1 May, was called off on the 11th, but only after Parliament had agreed to call a constituent assembly to discuss electoral reform.

However, the elections for the constituent assembly gave a majority to the Catholic party, which was against universal suffrage. Upon this the party called another general strike in April 1893. This time it lasted from 11 to 18 April, and again ended in a compromise. The Reform Bill which emerged multiplied the electorate tenfold, but reserved for some privileged sections the right of plural voting in the election of the Chamber of Deputies, while continuing to elect the Senate on a class franchise. At the first election under the new law, in October 1894, the Socialists won 355,000 votes and twenty-eight seats, both Édouard Anseele and Émile Vandervelde being returned. But with the provision for plural voting the party could have no hope of seeing the working class represented in full strength. The struggle for an equal franchise continued. In 1901 the Party Conference at Liège resolved to prosecute the struggle by every means, 'even, if necessary, through the general strike and insurrections'. In April 1902, the party called once more for a general strike, neither for the first nor the last time in the history of the Belgian Labour movement. Eleven years later the party called yet again for a general strike in the fight for equal voting rights. Reform came only after the First World War.

The Belgian Labour party differed in structure from most other parties in the International. It was not like, for example, the German Social Democratic party, a centralized organization based on individual membership in local groups, but a federation of trade unions, co-operative retail and productive societies, associations of employees in workers' health insurance, and educational, student and Socialist societies of various kinds. It was a party, as Carl Landauer described it, 'which not merely claimed to represent the worker politically, but also to negotiate for him with his employers, to provide him with facilities for buying his food and clothing more cheaply, for insuring him against illness, unemployment, and old age, for providing him with medical treatment and with opportunities for recreation and self-education'.[17] It was, as H. Pirenne remarked, 'more than an ordinary party. It makes the observer think of a state and a church in which the class spirit takes the place of the national or religious spirit'.[18] It depended for its finances on these affiliated societies, which spread rapidly after the foundation by Anseele of the famous co-operative association Vooruit in Ghent in 1850 and which, as Jean Volders reported to the Congress of the International, devoted some of its surplus to building the Socialist Press and the party's cultural institutions. The Belgian paryt could claim, said Volders, to be one of the best-organized in Europe.[19]

The struggle for the vote conducted by the Labour party in Belgium, and particularly its technique of street demonstrations, together with the political general strike, produced a considerable impact on the working people of Austria. In their own fight for universal suffrage, the left wing of the party urged the leadership 'to speak Belgian'.

The Social Democratic Labour party of Austria emerged from a merger between the 'moderates' and the 'radicals' at their conference at Hainfeld in 1888–9, a mere six months before the Congress of the International. It put an end to years of bitter dissention in a Labour movement which had begun promisingly enough at the end of the 1860s. In December 1869, 10,000 Viennese workers had demonstrated in front of the Parliament building for the right to form legal trade unions. Impressed by the size of the demonstration the government passed a law which permitted the formation of unions. At the same time it stepped up the repression against 'Social Democratic tendencies'. Ten days after the demonstration the Socialist leaders, including Andreas Scheu, Heinrich Oberwinder and Johann Most, were arrested. Six months later they were sentenced to heavy terms of hard labour on charges of high treason. Almost all working-class organizations, including trade unions, were then disbanded. Under the pressure of renewed street demonstrations the police eventually allowed them to re-form, and the imprisoned leaders were released under an amnesty. But the movement and its Press remained under strict police surveillance.

From the beginning the young Austrian Labour movement had modelled itself on the Gemran and considered itself virtually a branch of German Social Democracy. It consequently reflected the controversies which raged in the larger organization. In Austria the dispute became personalized in the struggle between Heinrich Oberwinder (1846–1914) and Andreas Scheu (1844–1927). Oberwinder owed some of his ideas to Lassalle. Claiming that a strong Labour movement could not grow in Austria while the country remained industrially under-developed, he called on the workers to form, for the time being, an alliance with the progressive bourgeoisie to fight for democratic and social reform against the ruling aristocracy. His followers described themselves as 'moderates'. Scheu, on the other hand, was a Marxist, demanding an uncompromising class struggle against the bourgeoisie as well as the aristocracy for the complete Socialist transformation of society. His followers were called 'radicals'.

As always and everywhere, what began as a genuine difference over principles and tactics soon degenerated into bitter personal antagonism. In 1874 both men abandoned the party, when Scheu left for England and Oberwinder for Germany. In England Scheu joined the Social Democratic Federation and later the Socialist League, working actively, right up to his death, for the ideals which had inspired him as a young man. Oberwinder's development in Germany was much less consistent. After joining the anti-semitic Christian Social party, founded by Stocker, Chaplain to the Prussian Court, he became editor of its paper. He was subsequently a foundation member of the chauvinist Navy League, founded by Admiral Tirpitz, and finished up as one of the main speakers for the 'National Executive', which functioned as a leading section of the reactionary, anti-Social Democratic 'Fatherland Union'.[20]

After the departure of Scheu, leadership of the radicals fell to Josef Peukert (1855–1910), one of the strangest figures in Austrian Labour history. Genial and impressive, he was adulated by his followers until, after two years, he was suspected of being a police informer.[21] Born in Bohemia, Peukert was an interior decorator by trade, a self-educated man of considerable learning. During his years of travel he came in contact with Anarchist groups in Switzerland and France. After being expelled from France in 1880 he arrived in England, where he established close relations with Most.

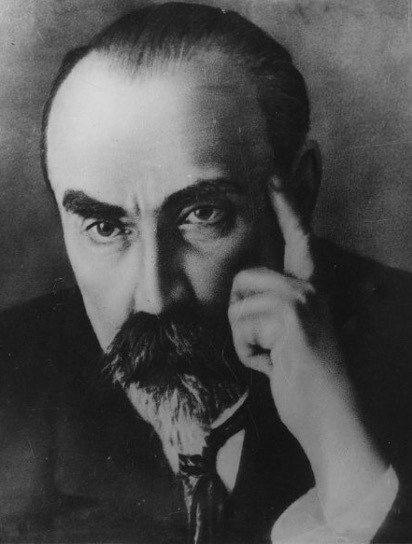

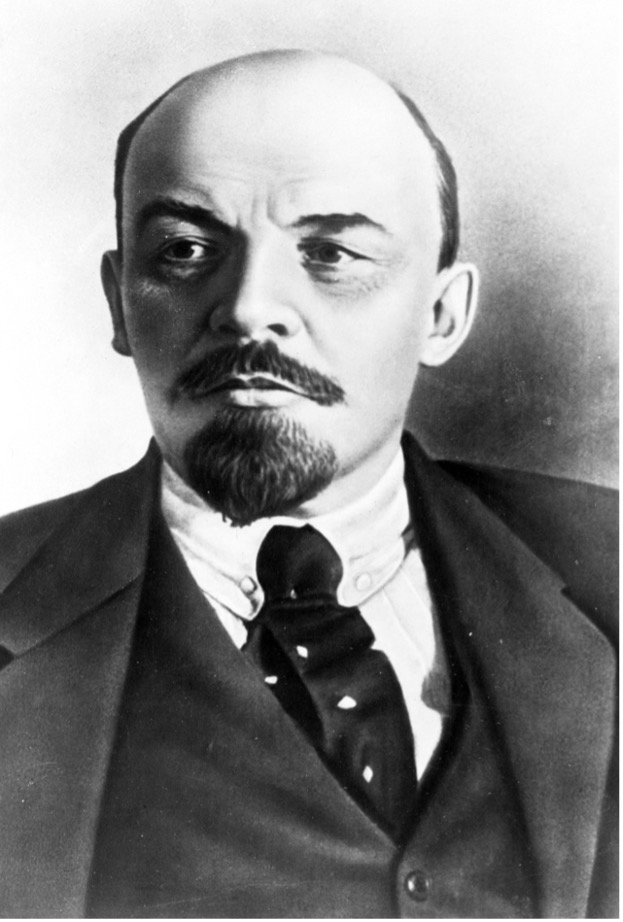

Johann Most (1846–1907) was among the leaders of the Austrian Labour movement who were tried for high treason in July 1870, Most being sentenced to five years' hard labour. After a few months, following on a change of government, he and his comrades were released and Most was deported to his native Germany. He had been born in Augsburg, the son of a poor subaltern, and after returning to Germany played a leading part in the Socialist movement for the next seven years. Elected to the German parliament in 1874 and 1877, Most was sentenced to eighteen months' imprisonment in 1874 for a speech in defence of the Paris Commune. After his release, huge public meetings were held in his honour, and he became editor-in-chief of the Social Democratic paper, Berliner Freie Presse. He came to enjoy, according to his friend Eduard Bernstein, 'an immense popularity with the mass of the people'. As soon as the Socialist Laws had been passed, he was expelled from Berlin and settled in London. There he founded, along with a number of members of the old German Communist Workers' Educational Society, the weekly paper, Die Freiheit, intended for illegal distribution in Germany.

An exceptionally talented journalist and an impressive public speaker, Most was aptly described by Bernstein as an 'undisciplined genius', impelled mainly by a revolutionary temperament and a messianic conviction that he was destined to be the 'saviour of the revolutionary spirit in Germany'. In this spirit, he used his paper to organize an opposition against the party leadership and the policy of cautious discretion imposed on it by the Socialist Law. In his conflict with the party leaders he gradually moved closer to Anarchism. He even glorified the stupid attempt to assassinate the ageing Kaiser Wilhelm I, which served Bismarck as a welcome pretext for his anti-Socialist legislation. A party conference in 1880, meeting secretly in Weyden, Switzerland, on account of the Socialist Law, expelled Most, and Die Freiheit, originally a foreign organ of the party's radical wing, now passed under the control of the Anarchists.[22]

Most was also sentenced to eighteen months' imprisonment by a London court for an article in Die Freiheit, justifying the attempt on the life of Tsar Alexander II in 1881, and recommending similar treatment for all heads of state 'between St Petersburg and Washington'. After his release he was deported from England and emigrated to America. He had a tumultuous welcome as a 'victim of bourgeois justice' at a specially convened meeting in New York in December 1882, and his propaganda tour, which took him to the main cities of the United States by the beginning of 1883, resembled a triumphal procession. The Anarchists, who had broken away from the Socialist Labour party of America, rallied to Most, and to Die Freiheit, which he again began to publish. There followed the tragedy of Chicago in May 1886 in which, after a bomb attack on a squadron of police who were trying to disperse a demonstration, four of the Anarchist leaders were hanged. This meant the virtual extinction of the Anarchist movement in the U.S.A. and, with it, the political career of Most.[23]

Of all Most's colleagues in London, Peukert had been the closest, and when he returned to Austria in 1881 he was greeted by the radicals as a 'genuine revolutionary'. Nor did he disappoint them. His pamphlets practically dripped blood. But this 'propaganda by deed' had frightful consequences. In July 1882 his supporters tried to rob a shoe manufacturer. In December 1883 they shot two policemen, and in January 1884 they killed and robbed the proprietor of a money-changing bureau. The culprits were arrested and hanged, numerous workers who had copies of Peukert's pamphlets were given heavy prison sentences, and a state of emergency was proclaimed in Vienna and the industrial areas of Lower Austria. The same night, according to Victor Adler, 'several hundred comrades were dragged from their beds and deported; those deported were deprived of their citizenship for all time'.[24] The night before martial law was proclaimed, however, Josef Peukert had left for America.

The state of emergency lasted for seven years. Juries for those charged with political offences were abolished, 'suspects' were deported after summary trial, many associations were dissolved and meetings were allowed to take place only with police permission and under police supervision. The regime of repression destroyed a movement which, ten years earlier, in 1873, had more than 80,000 members and had spread to every part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[25]

The Habsburg system of government, however, was described by Victor Adler as despotism mitigated by slovenliness; equally incapable, as he explained to the Congress of the International, 'of just rule and unjust repression, the Government alternated between both courses'.[26] It was this 'slovenliness' which enabled the movement to survive the repression and in 1886 it slowly began to recover. But it was still leaderless and crippled by the sterile strife between its 'moderate' and 'radical' wings—respectively Social Democratic and Anarchist.

Repeated attempts were made to bring the dissident factions together. They were all unsuccessful, until Victor Adler took up the task at the end of the 1880s. He was the real founder of modern Austrian Social Democracy, which came to life in Hainfeld on 1 January 1888.

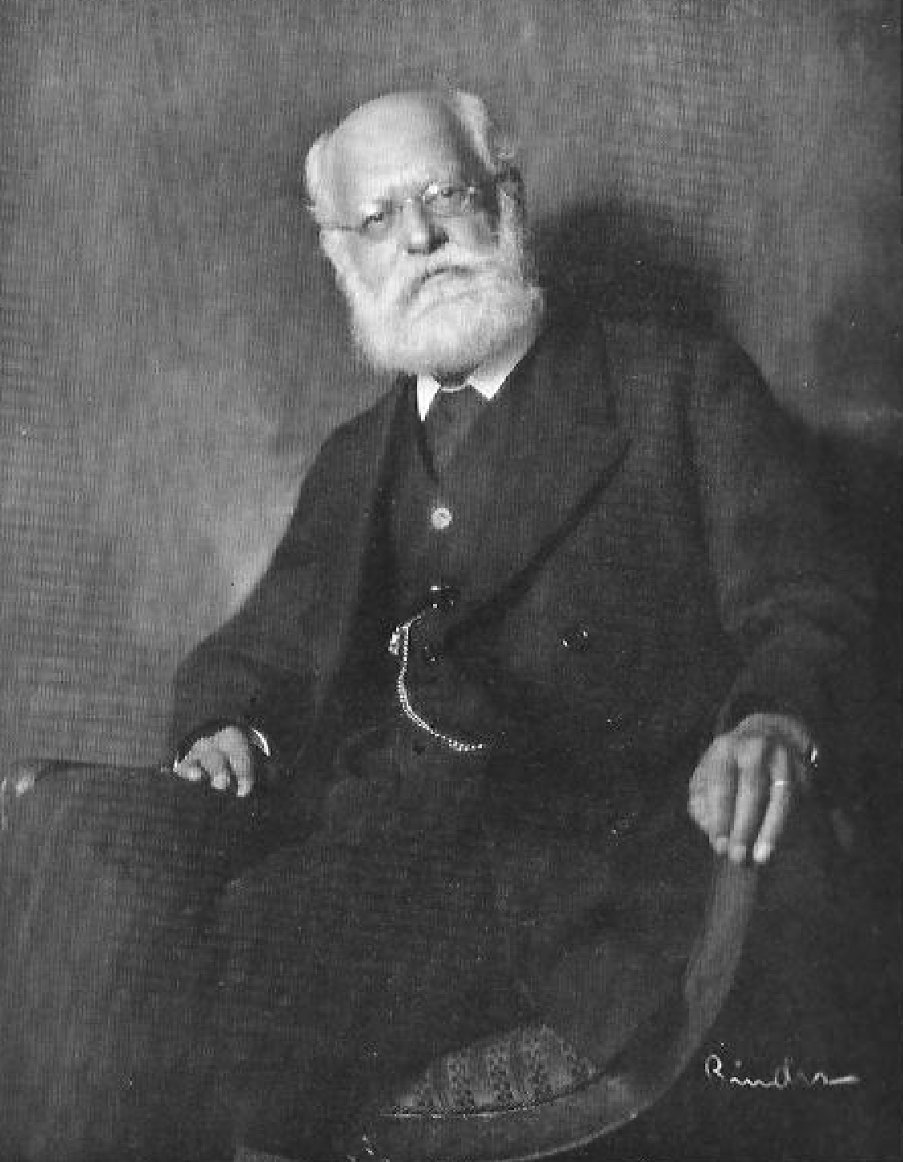

Victor Adler (1852–1918)[27] came from a well-to-do Bohemian Jewish family which had left Prague for Vienna in the 1850s. While still a medical student, he had joined the Democratic German Nationalist movement, which strove to establish a united national state in the spirit of 1848. As a doctor, working among the poor, he was moved by the sheer wretchedness of the poverty he found everywhere, and by the early 1880s his experiences had brought him close to the working-class movement. In the summer of 1883 he came to England to study the system of factory inspection, and after his visit to Friedrich Engels in London the two men formed a lifelong friendship.[28]

In December 1886, Adler used the fortune he had inherited from his father to found the weekly Gleichheit, forerunner of the famous Arbeiter-Zeitung. The paper helped to prepare the ground for a reunited working-class movement. Adler's personality, radiant with wisdom and warmth, won him the confidence of right and left in Austria and in the International. In Austria he enjoyed, right up to his death, a degree of affection and admiration accorded to no other leader of the movement. His prestige in the wider circles of the International was hardly less. Édouard Vaillant, the Blanquist, wrote of him: 'No one else in the International is surrounded with such love and friendship.' Émile Vandervelde, the reformist, testified:

I have known people who were more well-spoken, in the conventional sense of the term, than Victor Adler; others who have had a more profound effect on the development of Socialist thought; others, again, who were more deeply involved in world affairs and so more effective in a wider sphere of politics. But I have never known anyone—I repeat, anyone—who so combined in his own person all those qualities of character and understanding that go to make up the great party leader. He valued ideals without being blind to reality; he had a thorough grasp of doctrine and also of facts, a wonderful balance of mind and heart, a magnetic power which made him capable of moving the people with composure enough to restrain them in the hour of indignation. Above all, he combined an extraordinary capacity for adapting to circumstances with an inflexible pursuit of the central aim.[29]

The statement of principles adopted at the Hainfeld Congress, on which the factions were able to unite, had been drafted by Victor Adler and revised by Karl Kautsky. It expressed the aim of the movement in terms of Marxist concepts. It acknowledged the need for political struggle, which the Anarchists rejected, and of the fight for social reforms—'palliatives', as they were scornfully called by the Anarchists, who rejected them even more vehemently. But Anarchists could applaud its description of parliamentary government as a 'modern form of class rule', while reformists would welcome its demand for universal suffrage as 'one of the main vehicles of agitation and organization'. It resolved the hotly disputed question on methods of conducting the class struggle, on which the party had split, by declaring that in seeking to accomplish its aims, the party 'will use all means which seem appropriate and which conform to the popular conception of natural justice'—a formula which left the way clear for any method of struggle. It was acceptable to radicals as well as moderates, Social Democrats as well as Anarchists, although, in fact, it sealed the doom of Anarchism in Austria.

In Italy, Anarchism had found a different soil, and one more fertile than in Austria. Italy still had many of the characteristic features of early capitalism, in particular vast estates, owned by a landlord aristocracy and cultivated by semi-servile labour, a large, land-hungry rural proletariat, an urban proletariat living in wretched squalor and a large number of de-classed intellectuals. The Anarchist tactic of fighting poverty by direct action leading to insurrection had a natural appeal to the victims of such a social environment who were beginning to seek an end to their poverty. Moreover, the Anarchists in Italy were building on a tradition, brought there by Bakunin, which had gained considerable strength since the Risorgimento had begun the popular movement for freedom and unity. The tradition of conspiracy and secret societies, the armed coup d'état and 'propaganda by deed', was one hallowed by the memories of the patriots who had struggled against Austrian rule, and by the spirit of militant democracy which had been fostered in the underground movements led by Mazzini and Garibaldi. One of the leaders of Italian Anarchism, Errico Malatesta, wrote of the movement that:

The advocacy of violence was inherited by the Anarchists from democracy.…Our Italian Anarchists admired and honoured the armed uprisings of Agesilao Milano, Felice Orsini (both heroes of the Risorgimento) before turning to follow the theories of Bakunin. After affiliating to the International, they learned nothing in this sphere which they had not already learned from Mazzini and Garibaldi.[30]

When the Labour organizations of northern Italy, which had enthusiastically supported the Paris Commune, broke with Mazzini on that issue, they followed the intellectual leadership of Bakunin rather than of Marx. At its Rimini Congress at the beginning of August 1872, the Italian Federation of the International broke off all contact with Marx and the General Council, and refused to send a delegation to The Hague. After that, the Italian Federation became the bulwark of the Anarchist International.

At Rimini one of the most violent advocates of the break with the General Council was the young Andrea Costa (1851–1910) from Imola, whose teacher, Giousè Carducci, was then one of Italy's leading poets. Costa was still studying at the University of Bologna when, swept off his feet by enthusiasm for the Commune, he gave himself completely to the cause of the Socialist revolution. He first helped to build up the Fascio Operaio in Bologna, the organization which, by breaking with the Mazzinist movement and by its subsequent congress in March 1872, had founded the Italian Federation of the International. Costa became secretary of the congress at Rimini and a member of the delegation to the Anarchist Congress at Saint-Imier (September 1872). This was the congress which refused to recognize the General Council elected at The Hague, and which declared itself the only legitimate representative of the International Working Men's Association.[31]

Costa remained in Switzerland for some weeks after the end of the Saint-Imier Congress, planning with Bakunin the future development of the Anarchist International. The Italian Federation was to be transformed into the main instrument of the new International, and the programme which the two men drafted contained a directive which declared: 'Having complete confidence in the instincts of the mass of the people, our revolutionary objective depends on the release of what is usually termed "brutal passions" and the destruction of what the bourgeoisie call "public order".[32]

The subsequent history of the Italian Labour movement under strong Anarchist influence is a story of innumerable attempts to unleash in Italy a social revolution in accordance with the directive. In the years 1873–4 Italy, like Austria and Germany, was in the grip of an acute economic crisis, aggravated by poor harvests. Bread and meat became unobtainable for the continually growing mass of unemployed workers, owing to the rapid rise in prices. A wave of hunger-marches and strikes swept through the country. In the towns of Tuscany, bakeries and grain stores were pillaged, and the government turned troops out against the demonstrators. A 'revolutionary situation' seemed to have arrived.

The leadership of the Italian Federation decided that it was time for action. It set up a secret 'Italian Committee for the Social Revolution', to function as the revolutionary general staff. It was planned to start a rising in Bologna in the middle of August 1874 which would serve as the signal for risings in Tuscany, Romagna and Rome. By the end of July, Bakunin had arrived at Bologna from Locarno in Switzerland to help prepare for revolution.

According to their own figures, the Italian Federation then numbered a membership of 32,450, organized in 151 sections, Bologna being one of the strongest. But instead of the thousands which the general staff were expecting to turn out at zero hour, there were only a few dozen Anarchists available to seize the arsenals and rouse the masses to insurrection in Bologna, Imola, Florence, Leghorn and Rome. It was easy, therefore, for the police, who had had plenty of advance notice about the planned rising, to nip it in the bud. Not a single shot was fired, and the police picked up the handful of would-be revolutionaries who had been unable to escape. Bakunin, who had been waiting in his Bologna hideout for the revolution to start, fled to Switzerland the same morning, disguised as a parish priest.[33]

The pitiful collapse of the rising led to an opposition inside the party, centring around Enrico Bignami and his paper, La Plèbe. It called for the abandonment of Anarchist methods of conspiracy and violence and demanded the formation of a broad-based working-class party to fight for emancipation by legal means. Representatives of this trend came to be known as 'legal socialists'. But before the party could reach any decision, Cafiero and Malatesta organized another armed uprising.

Cafiero and Malatesta, together with Costa, then formed the triumvirate at the head of the Italian Anarchist movement. All three were selfless idealists, completely devoted to their cause. Carlo Cafiero (1846–83) sprang from the old and wealthy landed aristocracy of Apulia. After studying law at the University of Naples he entered the diplomatic service. He soon gave up his prospects of a brilliant career in diplomacy and moved to London, where he became friendly with Marx and Engels. From the latter he took over the task of building sections of the International in Italy, but when the great split came, he joined not Marx but Bakunin. During his short life he went to prison for his ideals, sacrificed the whole of a considerable fortune for the movement, and died quite destitute.[34]

Errico Malatesta (1853–1932) was also of non-working-class origin. Like Cafiero he had attended a Catholic school and then gone on to the University of Naples. Observing the appalling sufferings of the poor in Naples during the harsh winter of 1868, his heart, as he later described it in his memoirs, 'froze to ice'. 'I called to mind,' he added, 'the Gracchi and Spartacus, and I became aware that my soul was that of a tribune and a rebel.'[35]

In the uprising of 1877 Cafiero and Malatesta had discussed with Costa their plan for a renewed uprising. Costa opposed the project and refused to participate, but despite his objections, Cafiero and Malatesta went ahead. On 8 April, in the mountain village of Letino near Naples, an armed band of twenty-six men, bedecked with red and black cockades, and under the leadership of Cafiero and Malatesta, hoisted the red and black flag of Anarchism in the market-place, declared King Victor Emmanuel deposed and, to the delight of the peasants, burned the village archives. They then carried the 'revolution' to the neighbouring village. Meanwhile, infantry and cavalry had surrounded the rebel area and soon arrested all the insurgents.

The government had been fully informed of the conspiracy, the leaders of which had assembled several weeks before the uprising in a house rented by Malatesta in the village of San Lupo. They allowed them to proceed, unmolested, so as to catch them in the act and thus secure a pretext for a powerful assault on the entire working-class movement. Developments went according to plan. The Italian section of the Anarchist International was suppressed. 'Legal Socialists' as well as Anarchists were arrested in large numbers.

The fiasco of the conspiracy of San Lupo widened the gulf between the Anarchists and 'legal' Socialists. Andrea Costa had fled to Switzerland as soon as the police raids started. At the congress of the 'anti-authoritarian International' in Verviers, as also at the Socialist World Congress in Ghent, he continued to defend the insurrectionary policies of the Anarchists and denounced the proposed 'solidarity pact' with the Social Democrats. Nevertheless, his confidence in Anarchist doctrine had been shaken. After the attempt on the life of King Umberto in Naples by Giovanni Passanante, in November 1878, a new wave of exceptionally severe police repression against Anarchists and Socialists began. This forced Costa to the conclusion, as he put it, that 'insurrectionism, when put into practice, leads to nothing except the triumph of reaction, and when insurrectionist propaganda is not followed by action, its preachers fall into disrepute'.[36]

After the Ghent Congress, Costa settled in Paris. But, only a few months after his arrival, he was arrested, charged with being a member of the suppressed International, and sentenced to two and a half years in prison. Amnestied after twelve months he broke with the theory and methods of Anarchism. In July 1879 he wrote an open letter from Lugano to his comrades in Italy, in which he rejected both the tactic of insurrection and Bakunin's theory that the state must be destroyed as a first step, so that subsequently a society without a state could arise out of the ruins. Such a society, Costa now believed, would come neither out of a violent revolution nor through the decrees of a revolutionary government. It would emerge only from 'the natural consequences of a never-ending development of the productive forces, together with a new cultural outlook'. It was therefore relegated to the status of 'an ideal for the future'.

In the course of discussions on the revision of Anarchist doctrine, Costa called for the foundation of a workers' party which would aim at converting the masses to Socialism through a propaganda of social reforms such as a shorter working week, the legal protection of working conditions and restrictions on female and child labour. He also recognized the need to use Parliament, if only as an instrument of Socialist propaganda. He appeared, along with Amilcar Cipriani, as a representative of the Italian Socialists at the founding congress of the Second International in Paris.

At this congress, Cipriani played a major part in re-orienting the views of Italian Anarchists. Amilcar Cipriani (1844–1918) personified the revolutionary tradition of the Risorgimento. He had fought with Garibaldi at Aspromonte against the Piedmontese, in Crete against the Turks and in the Paris Commune against the troops of Versailles. There he was taken prisoner and deported to New Caledonia. Six years in the rigours of a penal settlement, however, failed to break his revolutionary spirit. Almost as soon as he arrived back in Italy, he joined in the 1877 conspiracy. But by 1889 he was in Paris, working with the 'legal Socialists' to re-establish the International.[37]

Before the 'Italian Revolutionary Workers' party' proposed by Costa could be founded, the 'Italian Workers' party' (Partito Operaio) was set up in May 1882, under the leadership of Constantino Lazzzari and Giuseppe Croce. This party rejected all ideology, seeing as its sole purpose the defence of the social and economic interests of the workers. Another ten years were to pass before an effective Italian Socialist party could be established. The way for it was prepared by the periodical, La Critica sociale, edited by Filippo Turati and Anna Kulischov. First appearing at the beginning of 1891, it became the most important organ of Democratic Socialism in Italy. In the same year, Turati founded the Lega Socialisti Milanesi (Milan Socialist League) and in the following year, in August 1892, the two parties agreed at the Genoa Congress to a merger which would exclude the Anarchists. The party founded in Genoa assumed the title of Partito dei Lavoratori Italiano.

The year 1893 saw a serious social unrest in Sicily. The brutally oppressed peasantry of the latifundia rose against their masters and occupied the land; the sulphur miners went on strike and there was street fighting between demonstrators and troops. At the beginning of 1894, Francesco Crispi, who had taken over the government of Italy with the slogan 'Socialism is the enemy', declared martial law. Parliament hurried through anti-Socialist legislation, and the young party, together with trade unions and other working-class organizations, was disbanded and the leaders arrested. But a year later, in January 1895, the party met in Parma for its third congress, assumed the title Partito Socialista Italiano, and at the elections in May 1895, with universal suffrage, almost trebled the earlier vote, increasing from 26,000 to 76,000.

Like Italy, Spain was a stronghold of Anarchism. Her economic structure, social and political instability and the tradition of pro-nunciamientos and conspiracies provided a favourable breeding-ground. A vast proportion of the land was owned by feudal landlords and bishops, industry was undeveloped and, except in Catalonia, was still in the pre-capitalist stage. For the millions oppressed by poverty and, in particular, for the masses of land-hungry peasants and urban workers, the revolutionary ideas of Anarchism seemed the perfect expression of their desperate indignation against intolerable economic and social servitude. Moreover, at the end of the 1860s, Spain had been shaken to its foundations by a series of dynastic and constitutional crises, military coups, proletarian risings and aristocratic counter-revolutions. There seemed to be all the conditions necessary for a social revolution.

The revolution duly arrived. In Cádiz, on 18 September 1868, the fleet and the army rose on a signal from General Prim. The Spanish Revolution of 1868, however, was, like the French Revolution of 1789, essentially a middle-class one. While at the outbreak peasants and workers united with the middle class against the hated Bourbon monarchy, the domination of the nobility and church, and the regime personified by Queen Isabella II, once the monarchy was overthrown and the Queen had fled, revolutionary unity disintegrated. The upper middle class aimed at a constitutional monarchy, free from clerical and feudal restraints; the middle class strove for a republic; and the working class was disorganized and leaderless.

Marx saw in the convulsions of this bourgeois upheaval no sort of preparation for a genuine social revolution. When the revolution broke out, the General Council of the International in London issued an address to the Spanish workers, advising them to organize and then unite with the republican wing of the bourgeoisie in the fight for a democratic republic. Bakunin, on the other hand, was sure that Spain was ripe for a social revolution. In November 1868 he sent Giuseppe Fanelli to Spain, with instructions to organize sections of the International which were to serve as shock troops for the social revolution. The first sections, formed in Madrid and Barcelona in December 1869, provided the basis for the Spanish Federation of the I.W.M.A., which was set up by the Anarchists in the following year, and which remained firmly under Anarchist control.[38]

Marx and Engels tried to destroy Bakunin's influence in the Spanish Federation. To this end, Paul Lafargue, a son-in-law of Marx and a refugee from the Paris Commune, went to Madrid at the end of 1871 and organized a Marxist opposition to the Bakuninist leadership of the Federation. The new group was organized round the journal La Emancipaciòn, edited by José Mesa, but Lafargue and the entire opposition leadership, including Pablo Iglesias, José Mesa and Francisco Mora, the historian of Spanish Socialism, were expelled from the Madrid Section in June 1872. After that they organized the New Madrid Section of the International, from which the Spanish Socialist party subsequently developed.

The Spanish Labour movement was consequently split from the outset both in its political and industrial sections. The Anarchist-led unions were grouped into the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo de España (C.N.T.), and those led by the Marxists into the Unión General de Trabajadores de España (U.G.T.). Most organized workers were in the Anarchist group.

The revolution, after dragging on for nearly five years, reached its peak in 1873. In February, the Cortes declared Spain a republic by an overwhelming majority. At the same time the Legitimists mounted an armed invasion and the workers rose in July, with bloody clashes in Lucar de Barrameda, near Cádiz, and in Alcoy. During the night of 2–3 January 1874, General Pavia, Military Commandant of Madrid, occupied the Parliament buildings, dissolved the Cortes and handed over power to a reactionary government. One of the government's first actions was to re-impose the decree prohibiting the International.

Despite persecution, however, the International was able to continue its activities secretly, and even publicly. When, after an attempt on the king's life in October 1878, the government arrested the Anarchists in droves and installed a regime of terror in Andalusia, the Federation of the International called for terrorist counter-measures. The appeal was followed by bomb attacks and landlords' houses were set on fire.

Pablo Iglesias (1850–1925) and his followers could only look on, as helpless spectators, while successive floods of Anarchism and reaction swept over the political scene. They had established the Spanish Socialist Workers' party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español) at the beginning of 1879. It drew its main support from the Printers Union of Madrid, of which Iglesias, himself a working printer, was a leading member. The party remained underground until, in 1886, it began publishing its official organ, El Socialista, and it did not function openly, as a party, until its congress of 1888. When its representatives appeared at the Paris Congress of the International in 1889, its support was still small and only slowly increasing. Its main strength rested in the General Union of Workers (U.G.T.), which it founded and led.

Meanwhile, the Anarchist Federation had disintegrated and its trade-union federation (the C.N.T.) dissolved. All attempts to re-unite the Labour movement failed. The Anarchists founded a new party, based on individual membership, while the trade unions of Catalonia set up a new, syndicalist, trade-union federation, with no party affiliation.

Anarchism in Spain and Italy had received its inspiration from Switzerland, specifically from Bakunin's Alliance of Social Democracy and from the Jura Federation of the International, which he controlled. But by the time of the Paris Congress, almost all traces of Anarchism had disappeared in Switzerland. Hermann Greulich (1842–1925) had, as a skilled craftsman, left Germany for Switzerland in 1865. He founded the Tagwacht, in Berne, and used it to propagate the idea of trade-union unity. By 1873, he had succeeded in uniting the unions into a centralized organization, the Swiss Workers' Association. But the new association remained completely non-party, concentrating its efforts on campaigns for social legislation.

Greulich, who had formed a Social Democratic party as early as 1870, saw it disintegrate after only two years. He then tried, along with Heinrich Scherrer, to win the Grütli Association, the first centralized working-class organization to appear in Switzerland, for Socialism. The Grütli Association had been founded in 1838 on the initiative of Albert Galeer and Dr Niederer, a friend of Pestalozzi, as a workers' educational and sick-benefit society, which also included radically-minded intellectuals and master craftsmen. In 1878 it adopted a programme with slight Socialist tendencies. It was only in 1888 that the Berne lawyer, Albert Steck, succeeded in merging the Union of German Workers, which had been founded on the inspiration of Wilhelm Weitling, together with various local Socialist organizations into a Social Democratic party of Switzerland. In 1901, this in turn amalgamated with the Grütli Association. By then the party had almost 10,000 members, and three representatives in the National Assembly, which representation it increased to seven at the following elections in 1902.

The party's definitive programme, adopted in 1904 and remaining operative for more than half a century, had been drafted by Otto Lang, a High Court judge from Zurich, and was overtly Marxist in tendency. In mood, however, as well as in political policy, the Swiss party tended towards Reformism, quite contrary to the influences emanating from the lively groups of German, French and Russian refugees who were particularly active in French-speaking Switzerland. Hermann Greulich, the leading figure in the movement, was a follower of Charles Fourier, as was Karl Bürkli (1823–1901), who also helped to establish the exceptionally strong co-operative movement in Switzerland. Another prominent leader of the Swiss party was Leonahard Ragaz (1868–1945), a professor at Zurich University and an influential representative of Christian Socialism in the Swiss Labour movement.[39]

In Holland, on the other hand, a movement akin to Anarchism developed more than ten years after it had disappeared in Switzerland. The first Dutch sections of the International were formed towards the end of the 1860s. They were represented at the Hague Congress, where they supported the opposition to March, without identifying themselves with the views of the Anarchists. In the period of reaction after 1872, the Dutch Federation disintegrated, and began to revive only under the influence of Nieuwenhuis's journal, Recht voor Allen, which first appeared, three times a week, in 1879, and daily from 1889. Under Nieuwenhuis's leadership the movement united into the Socialist League in 1881.