In the first three paragraphs of the preamble to the Rules, Marx had formulated the leading ideas of the International—ideas based on his own conceptions of history, philosophy and politics.

But the overwhelming majority of the International's members were not Marxist. Admittedly the delegates to the Geneva Congress in 1866 had unanimously adopted the Rules in Marx's draft. They accepted therefore the idea that 'the emancipation of the working classes must be won by the working classes themselves', as stated in the very first sentence of the preamble. They accepted, too, Marx's statement that the economic dependence of the workers on the owners of the means of production lay at the root of social misery and political subordination, and they also endorsed the statement in the Rules that 'the economical emancipation of the working classes is therefore the great end to which every political movement ought to be subordinate as a means'. But these ideas could be interpreted in different ways, and each school of thought in the International interpreted them in terms of its own favourite solution to the social problem.

The International included a very large number of schools of thought, with different and diverse aims. There were the representatives of anti-political, co-operative Socialism; representatives of reformist, syndicalist, revolutionary Anarchist and Utopian ideologies; followers of Proudhon, Fourier, Cabet, Blanqui, Bakunin, Marx—a chaos of mutually conflicting ideas. These differences were fought out at successive congresses in debates on the social and political programme. During the early years the debate centred on the differences between Marxism and Proudhonism, and in the subsequent period between Marxism and Anarchism. The history of the International's congresses is mainly a history of this battle of ideas, in which the movement tried to hammer out a common programme covering both the aims of Socialism and the methods of realizing it.

At the foundation meeting in St Martin's Hall it had been decided to hold the first congress of the International in Brussels in September 1865. Marx however was afraid that the chaos of social and political ideas, especially in the French working-class movement, would harm the reputation of the International. He convinced the General Council that it would be better to postpone the congress for another year, holding meanwhile a private conference in London.

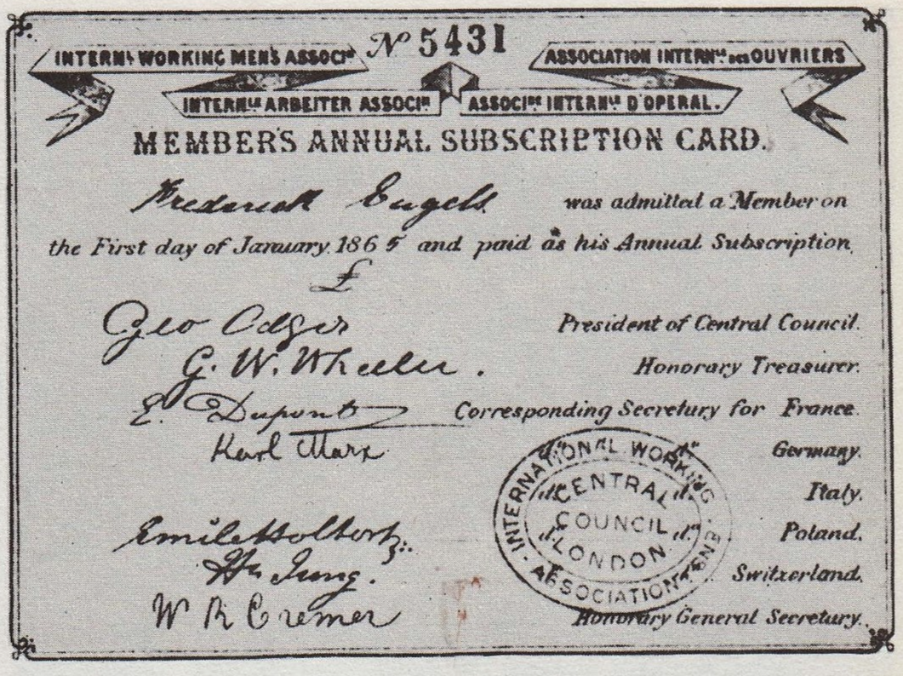

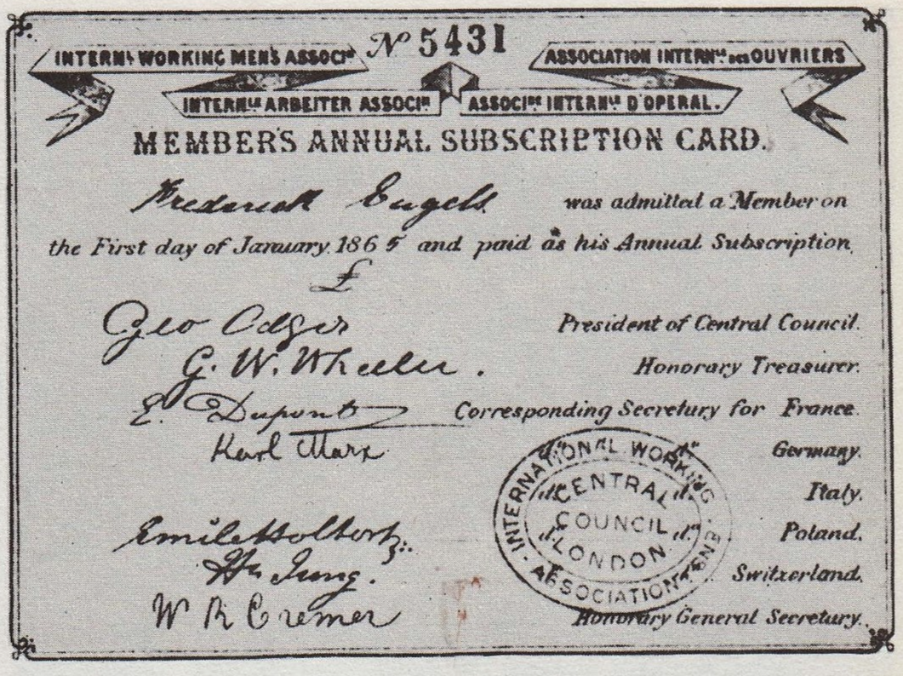

This conference met during the last week of September 1865, exactly a year after the foundation meeting. From the beginning, it revealed the movement's organizational weakness. Only four countries—England, France, Belgium and Switzerland—were represented. France was represented only by delegates from workers' organizations in Paris—Tolain, Varlin, Fribourg and Limousin—and by Eugène Dupont, corresponding secretary for France on the General Council. César de Paepe, the delegate from Belgium, and J. P. Becker and François Dupleix from Switzerland, could report only the first beginnings of a movement in their own countries. Germany was not represented at all. Schweitzer, president of the German General Workers' Association, had indeed published the Inaugural Address in his paper the Sozial-Demokrat, but his organization did not, as we have seen, formally affiliate to the International. The German element was represented at the conference only by Friedrich Lessner and Karl Schapper, delegates from the German Workers' Educational Society in London, by two corresponding secretaries on the General Council—Marx for Germany itself and Hermann Jung for Switzerland—and by Georg Eccarius, vice-president of the General Council. For Poland, Bobczynski represented the Polish National Society in London, and for Italy there was Major Wolff, Mazzini's secretary. By contrast the English delegation consisted of leading trade unionists such as George Odger and George Howell, Secretary and ex-Secretary respectively of the London Trades Council, and W. R. Cremer of the Carpenters, as well as a number of other prominent trade unionists serving on the General Council.

Differences between Marx and the followers of Proudhon were already apparent at this first conference of the International. It was concerned mainly with questions of organization and finance as well as with preparing the agenda for the congress called for the following year. The General Council had put forward a number of social questions for discussion, such as the length of the working day, female and child labour, trade unions and co-operatives. But the proposed agenda also contained a key political question: the role of Russia in Europe.

Marx saw in Tsarist Russia, that 'barbaric power', the main bulwark of European reaction. To weaken Russia by means of wars and national revolutions such as the Polish uprising seemed to him to be an essential part of the strategy of European democracy and proletarian revolution. He supported every political trend and every European power in conflict with Russia, including the despot power of Turkey during the Crimean War. He had singled out Tsarism for denunciation in his Inaugural Address and it seemed to him natural that at its first congress the International should range itself publicly in opposition to Russia.

The General Council had approved Marx's proposal to submit to Congress a resolution declaring that 'in order to stem the growing influence of Russia in Europe, an independent Poland based on democratic and Socialist principles according to the sovereign right belonging to every nation' should be established. The French delegation opposed the resolution, on Proudhonist grounds. Proudhon had been, on principle, against political action by the working class. Moreover he had opposed the movement of Mazzini and Garibaldi for Italian independence and unity and had repeatedly spoken against the restoration of Poland, even against the rising of 1863. His followers therefore rejected the General Council's resolution, but the conference decided by majority vote that it would go on the agenda for the forthcoming congress.

The General Council supported the resolution on Russian imperialism in a memorandum drafted by Marx as a guide to their delegates at the Geneva Congress which met in September 1866. The Polish question, argued the memorandum, was of the greatest importance in the struggle for working-class freedom, because Tsarism, the 'dark Asiatic power', was the last support of aristocratic and bourgeois rule in the face of advancing democracy. The power of Russia, however, could be broken in Europe only by restoring freedom to Poland. The fate of Poland would determine whether Germany would remain an outpost of the Holy Alliance or become an ally of republican France. So long as this great European question remained unsolved, the advance of the working-class movement would be constantly checked and thrown back.

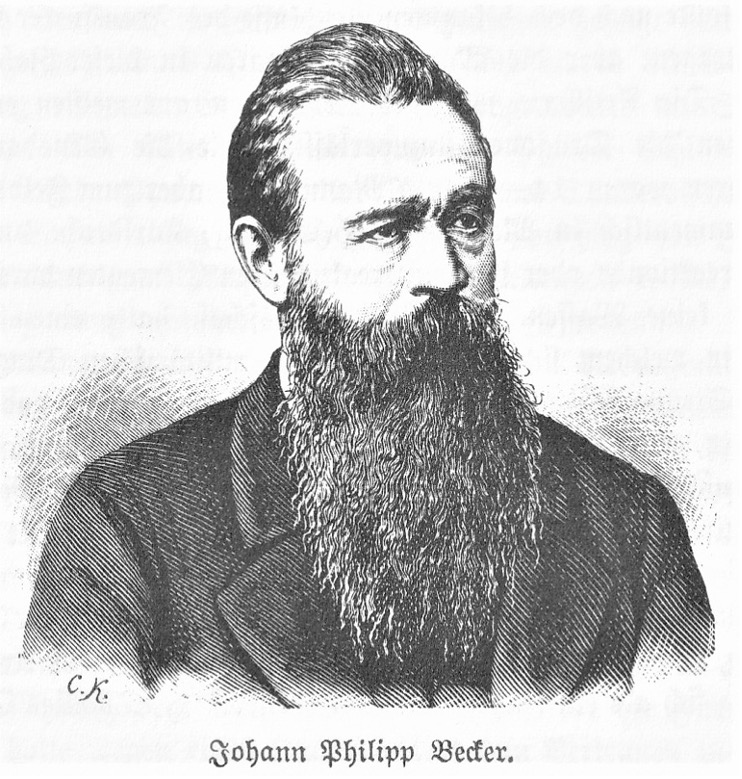

The French delegation at Geneva, supported by the delegates from French-speaking Switzerland, wanted nothing to do with the resolution. E.-E. Fribourg proposed that the congress should not commit itself over this 'complicated question of nationalities', but should confine itself to a general condemnation of despotism. The English delegates had no success in their efforts to persuade the Frenchmen, and an open split seemed likely. To prevent this, Congress finally agreed to a compromise resolution submitted by J. P. Becker. This, while it opened with a denunciation of despotism in general terms, went on to specify Russian imperialism and to call for the restoration of Poland's independence.

The Russo-Polish question was the only political issue debated at Congress. So far as social problems were concerned, Marx had drafted a programme which, as he explained in a letter to Kugelmann, was 'deliberately restricted' to 'those points which allow of immediate agreement and concerted action by the workers, and give direct nourishment and impetus to the requirements of the class struggle and the organization of the workers into a class'.[1]

In drawing up this programme, Marx was compelled to take fully into account the theoretical view of the French section. The alliance of the working-class movements in France and England seemed to him of supreme importance for the fate of the revolution which he believed to be on the way. He expected the rapid overthrow of the French Empire and hoped that, as in 1848, a revolution in France would touch off a revolutionary explosion throughout Europe. In an alliance between the workers of England and France he saw a necessary prerequisite to the triumph of the revolution as a whole. The International moreover provided the sole meeting-ground for representatives of the Labour movements in the two countries. It was the only organization which united them, and Marx was careful not to endanger this unity by allowing unnecessary theoretical disputes. The English trade-union leaders, with their pragmatic approach, did not represent a theoretical trend in the International. The French Labour movement on the other hand was still dominated intellectually by the ideas of Proudhon.

The new order of society for which Proudhon strove was based, as he put it, on the idea of justice. But a society based on justice required in his view the end of centralization in political and social life, since he regarded all authority, especially that wielded by the state, as incompatible with the principles of justice. He therefore saw, as he wrote to Pierre Leroux, 'in the abolition of exploitation of man by man and in the abolition of the government of man by man, one and the same formula'. He did not consider therefore that the principles of justice could possibly be realized in a Communist social order, since Communism was based, as he believed, on the principle of authority. 'Communism and absolutism,' he asserted, 'are the two faces of authority in a reciprocal relationship.'[2] To free the working class from capitalism, he advocated the development of producers' co-operatives; to free the peasants and handicraftsmen from the control of the merchants and bankers, he advocated a system of mutual exchange between small producers on a basis of equality, with free credit supplied by a People's Bank; and to liberate humanity from the authority of the state he proposed a free federation of autonomous communities and societies. It was inevitable that, at some point, the programme submitted by the General Council would arouse the hostility of the French delegation, although Marx hoped to avoid serious conflict by phrasing his programme as innocuously as possible.

The programme did express the main object of the International in the struggle between labour and capital. Its purpose aimed at 'combining and generalizing' the hitherto disconnected struggles of the workers in various countries. Its special task was to 'counteract the intrigues of the capitalists', who tried to play off the workers of foreign countries against their own employees in the event of strikes. 'It is one of the great purposes of the Association,' the programme declared, 'to make the workmen of different countries not only feel but act as brothers and comrades in the army of emancipation.'

The programme went on to deal with the limitation of the working day. This was another prerequisite for the emancipation of labour, not only 'to restore the health and physical energies of the working class' but also 'to secure them the possibility of intellectual development, social intercourse, social and political action'. The programme called for the legal eight-hour day and the limitation of night-work.

Juvenile and child labour, considered in the next section of the programme, was described as a 'progressive, sound and legitimate tendency' stemming from modern industry, although it became 'distorted into an abomination' under capitalism, 'a social system which degrades the working man into a mere instrument for the accumulation of capital, and transforms parents by their necessities into slave-holders, sellers of their own children'. The programme demanded legal measures to save the children of the working class from 'the crushing effects of the present system'. It propounded an educational policy in which mental education would be combined with physical and technological training so as to develop every side of the human personality.

Marx was sure that the Proudhonists would be up in arms against proposals to secure reforms through legal enactments. In their eyes, every law constituted merely another shackle on personal freedom. It was in combating this view that Marx appealed to the delegates to convert 'social reason into social force and, under given circumstances, there exists no other method of doing so than through general laws enforced by the power of the state'. The Proudhonists maintained that even benevolent laws would serve only to enhance the despotic power of the state; but, Marx insisted, 'in enforcing such laws, the working class do not fortify governmental power. On the contrary they transform that power, now used against them, into their own agency. The effect by a general act what they would vainly attempt by a multitude of isolated individual efforts.'

The programme turned next to the role of the unions in the working-class struggle for emancipation. This problem, too, Marx treated as he had treated the other social and political issues in the memorandum drafted for the General Council, as a problem arising out of the existing social system and in relation to his overriding preoccupation—the struggle of the workers against the capitalist system.

Capital, he emphasized at the outset, represented a formidable concentration of social power, whereas the worker, disposing of nothing but his individual power to work, was in a relatively disadvantageous position. The only asset the working class possessed was numbers. 'The force of numbers however is broken by disunion.' Trade unions were necessary therefore to prevent the workers from competing against each other. They were moreover a necessity in the daily conflict between capital and labour, aptly described by Marx as 'guerrilla fights', over decent working conditions, higher wages and shorter hours. But the trade unions had a more far-reaching task, that of serving as 'organized agencies for superseding the very system of wage labour and capital rule'. The unions must learn to 'act deliberately as organizing centres of the working class in the broad interest of its complete emancipation'. They should therefore support every social and political movement which aspired to these aims, and consider themselves 'the champions and representatives of the whole working class', not only of organized labour but also of the great mass of workers who had not yet reached the stage of industrial organization, notably the farm workers. In this way trade unionists would 'convince the world at large that their efforts, far from being narrow and selfish, aim at the emancipation of the downtrodden millions'.

The programme which Marx embodied in his 'Instructions' naturally failed to satisfy the French delegation. They rejected the strike weapons as 'barbarous' and recommended the workers to concentrate rather on developing co-operative associations in which, according to Proudhon's theory, the workers would enjoy 'the product rather than the wages of labour'. They protested in the name of 'freedom of contract' against the proposal for a legally enforceable eight-hour day, on the grounds that it was 'improper' for an international congress to try to 'interfere in the private relations between employer and worker'. With regard to the item on the agenda concerned with female labour, the French delegation had a resolution condemning it 'from the physical, moral and social points of view'. On the subject of trade unions the French proposed an amendment, also embodying the ideas of Proudhon, which stated that 'in the past the workers had experienced slavery, owing to the power of the guilds; in the present they are oppressed by legal obligations, amounting to anarchy; while in the future the worker will be producer, capitalist and consumer at the same time'. And on the General Council's resolution dealing with co-operative societies—based largely on Marx's view, expressed in his Inaugural Address, that co-operation, developed on a national scale and with national resources, could be a means of emancipating the people—the French requested that Proudhon's project of 'free credit' provided by an international People's Bank should be seriously considered.

Before Congress could debate the programme, however, it had first to consider the Provisional Rules endorsed by the General Council. The French delegation had put forward an amendment by which only manual workers would be eligible for membership of the International. This would of course have excluded Marx, though it was not specifically directed against him. It was based on a deep-rooted distrust of intellectuals among the French working class, who considered that they had often been betrayed by middle-class savants. Here the peculiar political conditions in France were particularly relevant. There was a vigorous and active Republican party led by middle-class intellectuals and politicians, as well as a conspiratorial movement aiming at a coup d'état, under the control of the Blanquists. The French delegation at Geneva stood for the development of a working-class movement based on trade unions and co-operatives, and they tried to avoid becoming involved in political questions. If the French section of the International were to take up political issues, they were afraid that the bourgeois Republicans or the Blanquists would take over the leadership of the movement.

The French view was completely unacceptable to the English and Swiss delegations. In their countries the Labour movement had long been accustomed to co-operate from time to time with radical bourgeois groups and middle-class intellectuals. As recently as February 1865 in England the unions had set up the Reform League with middle-class co-operation, to work for a reform of the franchise. They had co-operated with middle-class organizations in a campaign of public meetings which had rallied hundreds of thousands of workers in support, and was soon, in April 1867, to culminate in a major measure of electoral reform. Marx wrote to Engels, at the time, that he considered the foundation of the Reform League to be a 'great victory' for the International. 'The Reform League is our work,' he informed him. 'In the inner committee of twelve (six middle class and six workers), the workers' representatives are all members of the General Council.' He went on to say that 'should this re-invigoration of the political movement of the English working class succeed, our Association has without much ado already achieved more for the European working class than would have been possible in any other way'.[3] This campaign was of the greatest importance to the English trade-union leaders who were members of the General Council. They could not therefore allow their alliance with the middle-class Radicals to be jeopardized. The French proposal was rejected and the Rules proposed by the General Council were accepted with slight amendments.

After the congress had dispersed, Marx told Kugelmann in the letter already quoted that he had at first 'had great fears for the first congress at Geneva. On the whole however it turned out better than I expected.' He had of course heartily disliked the speeches and proposals of the French delegates. 'The Parisian gentlemen had their heads full of the emptiest Proudhonist phrases. They babble about science and know nothing. They scorn all revolutionary action, i.e. action arising out of the class struggle itself, all concentrated social movements, and therefore all those which can be carried through by political means, e.g. the legal limitation of the working day. Under the pretext of freedom and of anti-governmentalism or anti-authoritarian individualism, these gentlemen…actually preach the ordinary bourgeois science, only Proudhonistically idealized! Proudhon has done enormous mischief.'

But in the event the congress had accepted the essence of Marx's programme. It had acknowledged that the fundamental task of the working class was to destroy the wages system and develop a new social order founded on the power of the workers. It had pledged itself to demand the legal eight-hour day and a public system of popular education. It had accepted the need for working-class political action, and the power of the state as an instrument of social reform. Above all it had gone on record against Tsarism. Even George Odger, the president of the General Council, acknowledged in his report that the results of the congress had far exceeded his expectations. He was particularly enthusiastic about the reception of the delegates by the working people of Geneva.

The reception had indeed been magnificent—the delegation being led in solemn procession by a large crowd with colourful flags to the building in which the congress was held. Yet in reality the representation at the congress was not particularly impressive. Only three countries—England, France and Switzerland—had been formally represented. Of the total of sixty delegates, thirty-three had been Swiss and sixteen French (including Tolain, Varlin and, for the first time, Benoit Malon). From England the General Council sent six delegates—Odger, Cremer, James Carter, Eccarius, Jung and Dupont. Marx did not attend the congress, being busy completing the first volume of Das Kapital.

The Geneva Congress confirmed London as the seat of the General Council and re-elected the existing members. A week later, the General Council reassembled to hear a report from Odger on the congress. It then elected him chairman, with Eccarius as deputy chairman, Peter Fox as general secretary and Dell as treasurer.

The congress received a certain amount of notice in the Press, particularly in the growing number of working-class papers which were beginning to appear in France, Switzerland, Belgium and Germany. By the time the International held its first congress it had four official organs: The Workman's Advocate in England; Der Vorbote founded by J. P. Becker in Geneva; La Tribune du people, César de Paepe's paper in Brussels; and the Journal de l' Association internationale des travailleurs in Geneva. Besides these, a number of papers were appearing which were in general sympathy with the ideas of the International and carried reports of its first congress. This group included the Voix de l' Avenir of Dr Pierre Coullery, a delegate to Congress who published his paper in La Chaux-de-Fonds in French Switzerland; Fribourg's Courrier français in Paris; Henri Lefort's Avenir in Paris; J. B. von Schweitzer's Sozial-Demokrat in Berlin; and El Obero in Barcelona. The significance of the congress was also discussed in a number of bourgeois papers. The Journal de Genève praised 'the truly cosmopolitan spirit which inspired the congress'; and the Revue des deux mondes and the Revue contemporaine, both highly respected French periodicals, published, as Marx wrote to Engels, 'two detailed articles about the International, in which it and its congress are treated as one of the most important events of the century; similarly in the Fortnightly Review'.[4]

The International's second congress, which met in Lausanne at the beginning of September 1867, was also reasonably satisfactory from Marx's point of view. Although, in its efforts to bridge the gap, it passed a number of resolutions couched in Proudhonist phraseology and even embodying a few of the chief Proudhonist ideas, it was mainly a Marxist approach which it brought to the problems under discussion.

At Lausanne there were delegations from Germany, Belgium and Italy, as well as from England, France and Switzerland, which had been represented at Geneva. But of the seventy-two delegates attending the congress, more than half—thirty-eight in fact—came once again from Switzerland. The French delegation comprised nineteen members, and included Charles Longuet for the first time. The six delegates from Germany included Ludwig Kugelmann, a friend of Marx; F. A. Lange, the historian of Materialism; and Ludwig Büchner, the author of a widely-read book, Kraft und Stoff (Energy and Matter). Hwoever, the German delegation represented a few small local groups, and neither of the two large associations of German workers sent representatives. England had two delegates; Belgium one—César de Paepe; and Italy two: Gaspare Stampa and Sebastino Tanari. The General Council was represented by Eccarius, Dupont, Lessner and Carter. Marx once again did not attend.

For the second time there was a sharp expression of the two conflicting positions on the attitude of the working class towards the state. It started with a debate on whether the education of youth should be considered a state responsibility. A number of delegates called for state provision of legal, compulsory and secular education. The French delegation strongly opposed the suggestion. Longuet argued that schools under state control must become, like all state institutions, tools of the ruling class and instruments of political power. Tolain denied, as a matter of principle, that the state had a right to influence the education of children, which was the exclusive concern of their parents. The only exception he would admit was in the case of parents too poor to look after their children's education; in which case it became the state's duty to intervene. It happened, however, that working-class parents were usually too poor to provide for their children's schooling, so that the differences seemed largely academic. Congress therefore agreed on a rather ambiguous resolution, which satisfied the Proudhonists in form and the Marxists in content.

There followed a much more vehement debate on a topic which was central to the International and to the development of Socialism—the common ownership of the means of production and hence the economic basis of the future Socialist society.

The resolution before Congress, submitted by the Belgian delegation, dealt with the nationalization of the railways and other branches of the economy under monopoly control. There was naturally no opposition to the proposal that they should be removed from capitalist ownership. But who was to run these industries on behalf of the community? The co-operative societies, split into innumerable, small local groups, were hardly equipped for the task. As to the state, this was the main target of attack from the Proudhonists as a coercive instrument—the arch-enemy of personal freedom. They could not conceivably support a proposal which would actually increase the state's political power through expanding its economic base. The French delegates therefore declared themselves ready to vote for a resolution which called for the transfer of monopolies such as the railways to social ownership, providing that the form of social ownership remained unspecified. At the same time they raised the question of financial monopoly, and demanded that this should be broken by transforming private, capitalist banks into People's Banks operated for the public benefit.

Although the French formulation was accepted by Congress, this by no means ended the discussion on common ownership. De Paepe had called for the question of the public ownership of land to be included in the programme of the International. This was quite unacceptable to the disciples of Proudhon. For them, small landed property was a salutary bulwark of individual freedom, while they considered that agrarian Communism would be, as Coullery put it, 'collective tyranny'. After a vigorous debate, Congress decided to defer a decision until the following year.

The debate on common ownership had of necessity raised the question of the relation between politics and the fight for economic emancipation, and hence the role of the working class in political struggles. For Marx, working-class political action, developing into a struggle for political power, was an inseparable part of the fight against economic exploitation. The Proudhonists, however, saw all political power as necessarily an instrument of tyranny. Their objective was not, as with Marx, the conquest of the state as an organ of concentrated social power, but its complete abolition.

Congress attempted to bridge the gap with two resolutions. The first declared that 'the social emancipation of the workers is inseparable from their political emancipation' and the second that 'the establishment of political freedom is a prime and absolute necessity'. The first resolution could be interpreted à la Marx or à la Proudhon. The term 'political emancipation' could be taken to mean emancipation from the power of the state, for which the Proudhonists were striving, or the emancipation of the workers from political domination by the propertied classes through conquering the political power of the state, as advocated by Marxists. But while the first resolution was ambiguous, the second implied the necessity of political action, since if political freedom were to be recognized as a 'prime and absolute necessity', how, except through political struggle, could it be secured? Yet both parties considered the two resolutions to be of supreme importance as a statement of principles, and Congress accepted a further resolution stating that both declarations should be 'solemnly confirmed' at the beginning of every future congress of the International and that it should be particularly brought to the notice of all members.

Before this, Congress had turned to the role of the co-operative societies in the Labour movement. Supporters of co-operative Socialism hoped that they would become the means of peacefully transforming capitalism into a different economic system, based on co-operative values. But, some argued, might not co-operative societies which grew up inside a capitalist framework become in themselves a source of privilege, giving rise to an aristocracy of the working class which enjoyed higher standards of life through the economies of co-operative production? This was precisely the point made by de Paepe in moving a resolution on this subject which was passed by Congress. This warned against the danger of a 'fourth class' emerging from among the members of co-operative societies while the mass of the workers, constituting a 'fifth class', remained poor. This danger could be avoided only if it were stipulated that the profits of co-operative production should be ploughed back into the societies and not distributed to the members.

Congress considered another question which the General Council had agreed to put on the agenda, as to whether the working class could use for their own purposes the credit which, through the banking system, they made available to capitalists and their governments. The French resolution on this topic called for the establishment of People's Banks run on the basis of 'free credit'. The English delegation, however, proposed that trade unions should be asked to put their surplus funds at the disposal of co-operatives, so that the credit which, via the Banks, was put at the disposal of the ruling class, could be used to facilitate their emancipation as a class. If this were considered impracticable, then at least, the English suggested, they might be asked to deposit their funds in co-operative banks.

Finally, a political question of some delicacy remained on the agenda. A few days after the end of the International's congress at Lausanne, the League of Peace and Freedom was due to begin its own congress in Geneva. The League's Central Committee had invited the International to participate. The League of Peace and Freedom was an international organization of progressive intellectuals such as Victor Hugo and John Stuart Mill and politicians of the Radical middle class like John Bright; but it was also supported by such revolutionaries as Garibaldi and Alexander Herzen and its membership included the Socialists J. P. Becker, Bakunin and Louis Blanc. Bakunin was actually a member of its Central Committee.

The General Council, whihch had received the invitation from the League, had already devoted a good deal of time to considering the relationship between the two international bodies. While Marx insisted that the working class should have its own independent political party, he did not rule out in principle its co-operation with the progressive bourgeoisie for the achievement of political and social reforms. He welcomed the alliance between trade unions and the Radical middle class in the Reform League's campaign for the franchise. But he saw no point in co-operating with the Peace League, which he considered to be 'impotent'.

Most of the delegates to Congress, however, like the majority of the General Council, favoured co-operation between the International and the Peace League. But they demanded that the League should combine its concern for peace with a struggle for a new social order. Congress therefore passed a resolution declaring that the International was prepared to work with all its strength alongside the Peace League, to abolish standing armies and preserve peace, with the object however of freeing the working class from the rule of capital and founding a confederation of free states in Europe.

The resolution was too moderate for the French delegation. From its point of view, all co-operation with Radical middle-class politicians and with intellectuals was thoroughly undesirable. Tolain, supported by de Paepe, proposed the addition of a clause to the resolution which would make it quite unacceptable to a largely middle-class congress. Congress was to declare that, since the existing economic system with its contrasts between rich and poor was the real cause of wars, it was not enough to dissolve standing armies but it was also necessary to establish a new social system based on a just distribution of property. A delegation led by James Guillaume duly appeared at the Geneva Peace Congress, mandated with this resolution. Contrary to Tolain's expectation it was even carried, with 'tumultuous applause', though the Peace Congress then went on with its business as though nothing had happened, and there was no further reference to the International's resolution in the debates.

Of the two congresses, that at Lausanne was much more widely reported in the Press. The International was already regarded as a force to be reckoned with. It was with a note of triumph that Marx wrote to Engels: 'The lousy Star which tried to ignore us completely, said yesterday in its leader that we were more important than the Peace Congress.…Apart from the Courrier français, the Liberté siècle, Mode, Gazette de France, etc., carried reports of our congress.' In a subsequent letter, Marx referred to reports in the London Times. 'Things are on the move,' he added, 'and in the next revolution, which is perhaps nearer than it seems, we (you and I) have this powerful machine in our hands.…We can be well satisfied.'[5] In Marx's view, the second congress also signified an advance in the ideological development of the International. It had committed itself to the need for political action by the working class in its struggle for freedom, and had begun a decisive debate on the economic basis of Socialism.

The resumption of this debate at the third congress, in Brussels in September 1868, gave the congress particular significance in the history of the International. It was also the largest congress numerically, with a hundred delegates in attendance. More than half the delegates—fifty-six—were from the Belgian section; there were eighteen from France and twelve from the General Council and the English section, including the prominent trade unionist Benjamin Lucraft. There were also eight delegates from Switzerland, four from Germany including Moses Hess, and one each from Italy (Saverio Friscia) and Spain (Sarro Magallan). The General Council had invited J. B. von Schweitzer, President of the German General Workers' Association, to attend the congress, but he was then serving a prison sentence for lèse-majesté. Blanqui, however, who had been living in Belgium as a refugee since 1865, attended the Brussels Congress as a visitor.

The great significance of the Brussels Congress lay in its public commitment to the policy of nationalizing the means of production. So far, both in debates on the General Council and in the preparation of congress agendas, Marx had been careful to avoid discussing the issue directly. In all the basic documents which had so far appeared—the Inaugural Address, the Preamble to the Rules and the Instructions to Delegates at the Geneva Congress—there had been no attack on private property. For Marx the main thing was to unite the heterogeneous forces co-existing uneasily in the International, to strengthen the idea of working-class solidarity on a world scale, to stimulate by means of the International the development of working-class organizations and to strengthen them to play their historical role in the coming revolution. What happened at congresses was for him less important than 'the main thing', which was that 'congresses are taking place'[6] as a public demonstration of the unity of the international workers' movement. It was not from Marx, therefore, who was absent from the Brussels Congress, that the initiative came to force a debate on private property, but from César de Paepe, who had first raised the matter at Lausanne in the previous year.

De Paepe's resolution on common ownership was closely argued and had already been thoroughly discussed by the Belgian section. It stated that 'in a well-ordered society' of the kind to which Socialists aspired, the mines, quarries and railways should 'belong to the community, that is, to a new kind of state subject to the law of justice'. These branches of the economy should not be operated directly by the state but by co-operative societies with state assistance. The resolution went on to say that since 'the productive power of the land is the prime source of all wealth…the land and soil should be handed over to societies of agricultural workers' and organized on a co-operative basis. Finally, the resolution demanded that forests and public transport 'must remain the common property of society'. The delegations from France and French Switzerland naturally opposed what they referred to as 'crude Communism' in a debate of exceptional vehemence. The resolution was nevertheless carried with the support of the Belgians, English and Germans.

In a further resolution carried by the Congress the International dealt with the nature of co-operative production, which, under its programme, was to provide the main structure for the new economy. The resolution, which was carried, insisted that co-operative members should derive no privileges from their membership and should get no return in the way of dividend or interest on any capital they may have invested. 'Every society founded on democratic principles,' it stated, 'must reject all claims for a return on invested capital, in the form of rent, interest, profit or any other respect. The worker alone must have the right to the full product of his labour.' By the decisions of the Brussels Congress, the International was committed to the common ownership of land, farms, mines and railways. But these productive forces were to be operated not directly by the state but by co-operative associations of peasants and workers.

The other notable feature of the Brussels Congress was the debate on a question which was to recur throughout the entire history of the International: the attitude of the working class to war. The question was placed on the agenda by the German delegation, in the light of the current threat of war between France and Germany. The resolution stated that such an event would constitute 'a civil war in the interests of Russia'. Workers were asked to resist war by every possible means including, as de Paepe suggested, strikes and refusing to serve. The resolution, drawn up after a discussion between Tolain and Becker and then carried unanimously, called on the workers 'to cease work immediately' in the event of war. The resolution ended with the words: 'Congress counts on the solidarity of the workers in all nations to implement a people's strike against war.'[7]

The middle-class Press treated the Brussels Congress with respect, as representing a force which had now to be reckoned with. Shortly before the congress the London Times wrote about the International: 'One has to go back to the time of the birth of Christianity and the rejuvenation of the ancient world by the Germanic nations, to find anything analogous to this workers' movement which seems to perform, in relation to existing civilization, a service comparable to that which the Nordic barbarians rendered in the ancient world.' The aim of the International, said The Times, was nothing short of the rebirth of humanity, 'surely the most comprehensive aim to which any institution apart from the Christian Church has ever aspired'. The English, French, German, Swiss and particularly the Belgian press gave detailed reports of the congress, and discussed with expressions of alarm, which were to be expected, the resolutions dealing with the nationalization of land and mines.

The Belgian government had made strenuous efforts to prevent the congress from meeting in Brussels. The fact that, despite this, the congress was able to assemble and to carry through its business successfully brought the International a good deal of prestige, some of which was reflected in the newspapers. Several thousand workers had joined the Belgian section after the forcible suppression of a miners' strike in Charleroi by the government. The Belgian government was alarmed by the growth of the International. When it was announced that the congress was to be held in Brussels, Bara, the Minister of Justice, asked for a special Act of Parliament against aliens which would have enabled the government to expel foreign delegates. In his speech to the Chamber of Deputies, the Minister described the International as a conspiracy and a threat to the state. After the Bill was rejected by the Chamber, the Brussels section of the International issued an Open Letter to the Minister which was published in a number of papers, thanking him 'for the great service' he had rendered the International, 'in that you, Mr Minister, made the International the subject of a debate in the Chamber and so enabled us to use the official record of Parliament to propagate our ideas'.[8] It is also worth noting that the Brussels Congress paid special tribute to Das Kapital, which had been published a year earlier. A resolution which was unanimously carried claimed that 'Karl Marx deserves the very great credit of being the first economist to have subjected capital to a scientific analysis'.

At the following year's congress, at Basle in September 1869, the ideological struggle with Proudhonism reached its climax. The General Council had received a protest from the French against the decisions on the common ownership of land which had been reached at the Brussels Congress. There had been no adequate preparation for the debate, the French claimed, and after some discussion on the General Council it was agreed to submit the matter to another congress. The Congress Commission, which prepared the agenda for Basle, divided the subject into two separate resolutions, one declaring that society had the right to establish common ownership of land and the other that it was necessary to do so.

The first resolution was opposed on the grounds that prolonged occupation of land by a family ought to imply some property rights, and that where cultivation had enhanced the value of a farm the increased value belonged by right to the farmer. A majority of the Commission, however, argued that land had originally been common property and had been acquired by private owners only through the ruthless use of political and economic pressure. Society therefore had the right to make good this injustice. Opinions were also divided on the question—apart from the right of society to reassume ownership of the soil—of whether it was necessary. Eventually a resolution was carried by fifty-four against four (with thirteen delegates abstaining), affirming that 'society has the right to abolish private property in land and soil and to transfer it to collective ownership'.

'This left open the question of how the commonly-owned lands should be administered. A majority of the Commission recommended that the farms should be run by elected parish councils. A minority wanted them to be controlled by agrarian co-operative societies. Finally, the General Council, represented by Eccarius, suggested that large-scale, mechanized farms should form the basis of a socialized farming system managed by producers' co-operatives. As there was no agreement in sight, the discussion was adjourned to the following year.

The decisions of the Basle Congress in favour of common ownership was all the more important as it was the most representative congress ever to be held by the International. For the first time Germany was directly represented by one of the two workers' parties—the Social Democratic Workers' Party, founded by Liebknecht and Babel. This was also the first occasion on which delegates from Austria had been allowed to attend. A delegate had been sent by the National Labor Union, still the most important trade-union association in the United States. Finally, and most significant of all, it was the first congress attended by Bakunin and at which the banner of Revolutionary Anarchism was openly displayed.

Altogether, there were righty-seven delegates at Basle. Six represented England and the General Council, including the prominent building worker, Benjamin Lucraft, and Robert Applegarth, Secretary of the Carpenters and Joiners Union, one of the largest unions in Britain. There were twenty-five from France, including, besides Henri-Louis Tolain and Eugène Varlin, who had been released from prison a short time earlier, Michael Bakunin representing the section at Lyon. There were twenty-three delegates from Switzerland, including Hermann Greulich, who later established the Swiss Social Democratic party. Twelve delegates attended from Germany, including Wilhelm Liebknecht as well as Moses Hess, and five from Belgium, led by César de Paepe. Henrich Oberwinder and Ludwig Neumayer were there from Austria: they were soon to face a treason trial at home because of their support for the International. The Spanish section was represented by Gaspar Sentinon and Rafael Farga-Pellicer. The Italian section was represented by Stefano Caporusso, and also by Bakunin, with another mandate. The delegate from the National Labor Union in the United States was Andrew C. Cameron, editor of the Chicago working-class paper, the Working Man's Advocate.

Before his decision to adhere to the International, Bakunin had tried to win over the Peace League to his brand of Revolutionary Anarchism. One of the chief planks in his platform was the abolition of the right of inheritance. After breaking with the League he tried to win the International for this demand. With the support of the French section the question was placed on the agenda at the Basle Congress.

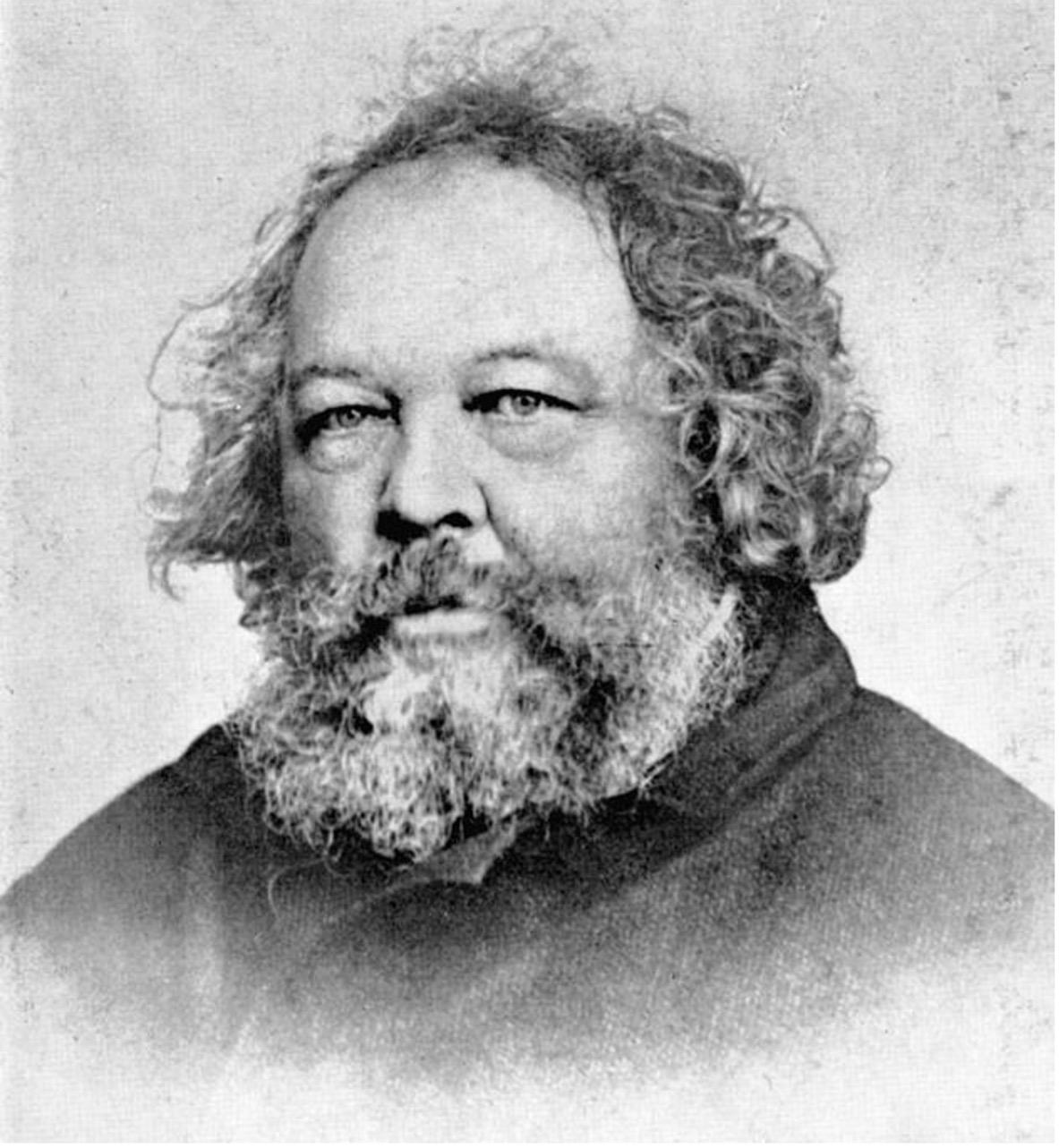

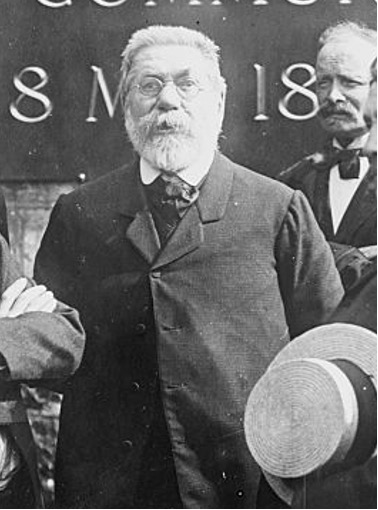

Michael Bakunin (1814–76), son of a Russian aristocratic landowner, became the most powerful exponent of Revolutionary Anarchism. Of enormous stature and with unusual charm of manner, Bakunin combined immense powers of conviction, an explosive temperament, a taste for macabre conspiracy and a certain naïve truculence. He was happy to sacrifice himself in the cause of freedom.[9] Wherever revolution broke out, Bakunin was likely to be on the scene, and he took part in both the Paris rising of February 1848 and the Dresden insurrection of May 1849. After the defeat in Dresden, Bakunin fled and was captured by Prussian troops. He was twice sentenced to death by courts martial, the first time in Prussia in 1850, the second in Austria in 1851. The Prussians handed him in chains to Austria; the Austrians transferred him, still chained, to the Russians. Imprisoned at Olmütz he spent six months with his hands and feet chained to the walls of his cell. The Tsar kept him in solitary confinement for more than seven years, first in the Peter and Paul Fortress, then in the Schlüsselburg. Finally he was banished to Siberia for life. He escaped in 1861, and after about three years of exile in London he resumed his revolutionary agitation in Italy and Switzerland. With all the glamour of legend, Bakunin appeared—the personal incarnation and symbol of revolution—at the Basle Congress.

In a persuasive speech he defended his demand for the abolition of the right of inheritance. This right, he argued, was the basis which supported the institutions of private property and the state. Once the right of inheritance was abolished, the entire social system resting on private property would break down. The abolition of the right of inheritance was therefore one of the 'fundamental conditions' for the abolition of private property itself. It was the prerequisite of social revolution.

Marx, who did not attend the Basle Congress, had drafted a statement for the General Council which was presented by Eccarius as secretary. The right of inheritance, according to Marx, like the laws of commercial contract, was not the cause but the consequence of a society based on private property. The right to inherit slaves had not been the cause of slavery: the institution of slavery was the reason why slaves could be inherited. If the right of inheritance was abolished, this would in no way destroy an economic system based on private ownership of the means of production. On the other hand, if the means of production were transferred to public ownership, this would be tantamount to abolishing the right of inheritance.

Neither side secured an effective majority. The report of the Congress Commission, which took Bakunin's point of view, received thirty-two votes in favour, twenty-three against; there were thirteen abstentions and seven delegates were absent. The General Council's report received nineteen votes in favour, thirty-seven against; there were six abstentions and thirteen absences. Since neither side had a majority among those eligible to vote, the question remained undecided.

The voting however showed the considerable influence which Bakunin had already secured in the International. In Marx's view it was a highly dangerous influence, and he was sure that Bakunin's fantastic aims could only confuse and disorganize the working-class struggle. For Bakunin repudiated all authority and all restrictions on personal liberty. In the omnipotence of the centralized state and its institutions he saw, with Proudhon, the essential denial of freedom. He was convinced that as long as the existing political and social institutions survived there was no possibility of securing economic emancipation for the workers. He therefore preached the destruction of all existing institutions, 'the state, the church, the banking system, the university institutions, the Civil Service, the army, the police—institutions', he claimed, 'which are merely fortresses erected by privilege against the proletariat'. The state itself, he declared, 'be it absolute monarchy, constitutional monarchy or even republic, means domination and exploitation. It means domination of one dynasty, nation or class over another: a manifest denial of Socialism.' However the state may be constituted, however 'embellished with democratic forms, it will always be a prison for the proletariat'. In some ways a democratic republic could be worse than an absolute monarchy. 'Just because of its democratic façade,' he claimed, 'it enables a rich and greedy minority to go on living on the backs of the people in peace and security.' Bakunin's aims, like those of Proudhon which had so strongly influenced him, were 'a free grouping of individuals into communities, of communities into provinces, provinces into nations and, lastly, nations into united states—first of Europe, then of the whole world'.

Bakunin's guiding idea was 'collectivism', in contrast to Marx's 'Communism', which Bakunin called 'State Communism'. 'I am not a Communist,' he explained, 'because Communism, by concentrating all property in the state, necessarily leads to the concentration of all the power of society in the state. I want to abolish the state; my aim is the complete destruction of the very principle of state authority which up to now has meant the enslavement, suppression, exploitation and humiliation of mankind.'

Bakunin rejected all political action by the working class which did not aim directly at social revolution. He opposed participation in parliamentary elections, campaigns for social reforms and all attempts to win influence and power in the state. He condemned all such political activity as a 'betrayal of the revolution', since it gave rise to illusions among the workers that they could be emancipated by means other than revolution. He called on the International to concentrate its efforts entirely on social revolution. His method was the same as Blanqui's: the conquest of power by a coup, a putsch or an uprising. 'Every revolt is useful, however fruitless it may seem,' he maintained. Proudhon's Anarchism rejected the forcible overthrow of social institutions. Bakunin's Anarchism relied on force.

Up to the time of the Basle Congress, the ideological differences in the International had been confined to two tendencies: the federal, Anarchist anti-collectivism of Proudhon and the centralized Communism of Marx. At Basle a third tendency, Bakunin's federal, Anarchist collectivism, had appeared.

We have seen how the influence of Proudhonism grew less at successive congresses. The Basle Congress gave the final blow by including land nationalization in the programme of the International, in flat contradiction to one of the basic principles of Proudhon. Moreover, in France and particularly in Paris, Tolain's leadership was being challenged with growing success by Eugène Varlin, and Varlin, though still a federalist, had abandoned his earlier Proudhonist views. He had become a collectivist, although he never adopted a fully Marxist position. At Basle, Marx's views were supported completely by the English, German and German-Swiss delegates, while on collectivism he had the additional support of the Belgians and Anarchists from the Latin countries. However, the German delegation represented little real strength at Congress, since neither of the two workers' parties in Germany had affiliated to the International, and its strength both in local sections and in individual membership remained modest. More modest still was the individual membership in Austria, where such working-class movement as there was did not yet constitute a party. In German Switzerland, the workers' associations co-operated with progressive bourgeois parties. Bakunin's influence was spreading both in French Switzerland and in the south of France, while his followers had the greatest influence in the Italian and Spanish sections. On most issues, too, the Belgian section led by César de Paepe was closer to Bakunin than to Marx. In the International therefore Marx's position depended only on the support of the English union leaders and the groups of German exiles in London.

Nevertheless, two of Marx's principles had triumphed in the battle of ideas being waged inside the International. Congress had endorsed both the necessity of political action by the working class and the common ownership of the means of production. But the battle of ideas did not end with the adoption of these principles. On the contrary, the future history of the International was to be preoccupied with the clash between Marxism and Anarchism.

During the five years which had passed from the foundation of the International to its Basle Congress, its influence among the workers had spread with unexpected speed. Though its organizational base was feeble it had come to be regarded, by both rulers and ruled, as a power in its own right. Was it, however, really so powerful? And was not its potential being sapped by internal ideological disputes? In the year or so following the Basle Congress, the Franco-German War and the Paris Commune were to subject the International to a crucial test.

1. Karl Marx, Briefe an Kugelmann, p. 31. For the text of the programme submitted to the Geneva Congress under the title 'Instructions for the Delegates of the Provisional General Council: the Different Questions', see Documents of the First International, 1864–6 (London, 1963), pp. 340–51.

2. Max Nettlau, Der Anarchismus von Proudhon bis Kropotkin (Berlin, 1924), p. 6.

3. Marx-Engels Briefwechsel, vol. III, p. 315.

4. Marx-Engels Briefwechsel, vol. III, p. 441.

5. Marx-Engels Briefwechsel, vol. III, p. 500.

6. Marx-Engels Briefwechsel, vol. III, p. 500

7. For a detailed account of the debate on this resolution, see The International on War, ch. 21, Part 3.

8. Meyer, Der Emanzipationskampf des vierten Standes, vol. II, p. 216.

9. There is a short and sympathetic biography in German by Georg Steklov: Michael Bakunin (Stuttgart, 1913); and a more detailed life in English by E. H. Carr: Michael Bakunin (London, 1937). There are a few surviving copies of Max Nettlau's monumental biography, of which one is in the British Museum and another in the International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.