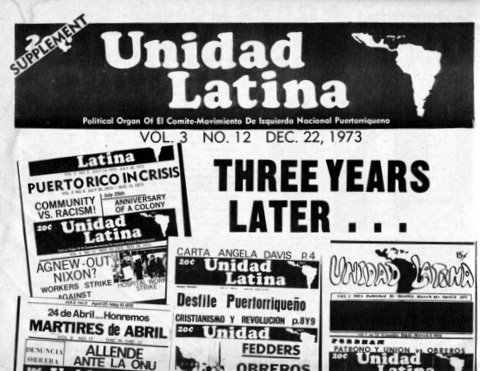

First Published: Unidad Latina, Vol. 3, No. 12, December 22, 1973.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

On March 10, 1971 we published the first edition of Unidad Latina. Today, almost three years later we’ve decided to temporarily suspend its publication, the political reasons for this decision are explained in the accompanying statement as drawn by our Central Committee and approved by El Comite. We urge all of our readers and friends to closely read and study the statement as it raises some questions that we think are fundamental to us, to the Puerto Rican people living in the United States.

The temporary suspension of our political-propaganda organ does not mean that our organizational work will stop, on the contrary, our workers and community sectors, along with F.E.P. (Frente Estudiantil Puertorriqueno), the student front, will now increase their work as well as consolidating their, organizational tasks. These decisions respond to discussions within El Comite, discussions and analysis which were postponed as a result of our involvement during the planning of the March on Washington of October 30, an activity which we felt was one of urgency and priority.

As a newspaper UNIDAD LATINA has been self-sufficient, from its first edition we stated we would not accept any paid advertisements and its production would be the collective work of the members of the organization. The nature of both the paper and the organization facilitated this task. Responding to the direction given by the work of the organization UNIDAD LATINA attempted to bring out the many problems affecting the Puerto Rican/Latin community in New York. As an organization, El Comite was a direct result of one of these problems or rather El Comite came into existence as a result of the spontaneous reaction of our people to these problems. We were basically a community organization, UNIDAD LATINA would be a community newspaper.

Living in communities populated by Puerto Ricans as well as other Latin-American we were to develop great interests and preoccupations about Latin America and its relationship to Puerto Rico. The name chosen for the newspaper reflected these preoccupations. In our first issue we wrote: “Not only are they exploiting our countries but here in the U.S. they exploit all Latinos and the rest of the Third World. We suffer the same conditions... we are forced to live in the worst slums of the city. Proportionately we pay more per room than any other group in the U.S.A. And when we happen to have the money we can’t just live wherever we want, the racists discriminate against us. We work in the factories, in the “sweat shops”. We receive the lowest wages. Schools teach our children that our people are lazy, that our countries are poor, that Latinos are inferior, that the American-way of life is superior, that our history, is either shameful or insignificant, that Spanish should be forgotten and only english should be spoken”.

In content and form UNIDAD LATINA was to be simple, it would be the mechanism by which we would denounce the existing oppressive conditions in our communities. The content presented very little in terms of alternatives or analysis of why things were the way they were.

As the organization, El Comite, expanded its work beyond the “community” limits, UNIDAD LATINA began to reflect these changes.

Our relationships with political organizations, such as the Young Lords and MPI, had its effects on the organization, a political character was developed. We became involved in issues not typical of a community organization such as defense of our political prisoners, rallies, strike support, etc... a process of transformation began but still our main focus remained localized on community work. This phase is explained in the accompanying political statement of our organization.

In September of 1972 we published our first theoretical document which brought about serious discussions within the organization and sectors of the Puerto Rican movement. We began to seriously study and apply Marxism-Leninism to our work. In March of 1973 during the commemoration of the Ponce Massacre we stated our intentions of setting the base for the organizational transformation to the Movimiento de Izquierda Nacional Puertorriqueno (National Left Movement of Puerto Rico).

With these stated objectives we still maintained our old methods of work, an obstacle which was further complicated by the tasks assumed by our organization in other areas, such as the mobilization to Washington. This internal contradiction have led to confusions as well as a marked gap between the newspaper, UNIDAD LATINA, and the organization, El Comite. We failed to realize that the political organ is very much part of our over all transformation, we also failed to realize that the whole process of transformation demanded a change within the internal structure of the organization. This we will accomplish. Our organization and its political organ must have an, even development otherwise we would become that which we have so often criticized, paper sellers, distributing an organ of propaganda but not an organizational tool.

* * *

UNIDAD LATINA has suspended its publication for an indefinite period of time. We hope this temporary suspension of publication will be a brief one. The decision based on two aspects, one being the difficulties we encountered in its development and the other, and most important, is the political situation that as an organization we are confronting.

In its beginnings UNIDAD LATINA was based on the same philosophy that gave guidance to El Comite. The newspaper served its function within the context of community work. The paper attempted to deal with the daily problems affecting “the people” of our community, describing their reality, discussing their problems and serving the people. The objective of serving the people ”Underlined the need of organizing at the community level, promoting community solidarity and assuming control over it and its destiny. Articles in the newspaper, both in content and presentation, reflected the various levels and forms of oppression existing within our community.

At the same time that the articles indicated similar conditions in other places, their analysis was based on the relationships between rich-poor, oppressor-oppressed, whites and the Third World.

In order to publish the newspaper it was necessary to have a staff of people in direct contact with the community and an editorial staff that would organize the information received. In short, the publication of the paper demanded very little specialized resources. In a way, this was and still is the case and experiences of a number of community newspapers that appeared in N.Y. and other cities during the years 1968-1972.

The idea was to publish a newspaper for “the people”, one that could be understood and of interest to Mrs. Lopez, a newspaper that would reflect her everyday problems. These publications were geared to the “non-political” masses (read non-rhetorical); it confronted their “real” problems, therefore truly political. Almost always this resulted in an undetermined emphasis in the “real” as the “concrete” and immediate; the items that “interested the people” became a formidable obstacle to any serious theoretical-ideological analysis. These discussions were included, as last resort/in the final pages.

We thought “the people” understood the causes and consequences of the situation, that having experienced oppression was worth more than any political education and that the problem was to unite “the people” and once they were united they would deal with the rest. The base for this unity was exclusively a common community, nation and/or race, on this point we can seriously speak of the existence of a cult of spontaneity.

The extensive and impressive surge of this type of publication throughout the Northamerican nation during the last decade, reflected in one hand the growth of spontaneous mass struggle a phenomena that took place in all levels and on the other hand it showed the lack of political and organizational experiences of its leaders.

Nevertheless, once the newspaper was established, its development was not parallel to the organization. From its very beginnings the organization had as its goal the liberation of Puerto Rico. This anti-imperialist position, intensively nationalist, would give direction to the newspaper. It was committed to all manifestations of anti-imperialism, in particular events in the Caribbean and Latin America. Forced to discuss situations of oppressions and injustices in other parts of the United States the newspaper had to go beyond the limits of community work and this led to the newspaper going ahead of the organization in its political conceptions. Even so, the limits of the newspaper were established by the level of development, the organizational and political experience of the organization.

It is not this article’s intention to discuss the dialectical relationship between newspaper and organization. It is sufficient to state that we arrived at the point in which the discrepancies between, methods of work and political positions led to crisis; if we did not overcome the narrow horizons of our local work and if the organizational apparatus was not transformed we would not be able to survive the collapse. The vacillations of UNIDAD LATINA clearly showed the contradictions of attempting to advance our political development without having the correct and in depth organizational structure.

In a similar situation, Lenin made a statement that our experience proved correct: “It is positively beyond the strength of a separate local organization to maintain stability of principles in its newspaper and raise it to the level of a political organ. It is beyond its strength to collect and utilize sufficient material to cast light on the whole of our political life.” (What Is To Be Done, P. 178). The Watergate and energy crisis, the political developments in Puerto Rico, the problem of building a truly communist party in the U.S., the present situation of the economy... all of these are important issues to our struggle and they made evident our limitations. We felt that the “independentistas” or patriotic Puerto Rican organizations were committing a criminal act by remaining silent; by ignoring Watergate and by allowing this critical political juncture to go by without giving directions to our people. Yet, at the same time we were not in a position to remediate and we didn’t have the resources to do it. It’s no longer possible to justify the continuing state of things.

The second aspect of the situation that precipitated the suspension of our publication was what has become known as “the national question”, which is nothing more than taking a position in respect to the role of the Puerto Ricans in the proletariat revolution of the United States, and the existing relationship between this and the national liberation struggle of Puerto Rico, the building of the socialist republic, and lastly, the creation of the revolutionary instrument of struggle, the party, an essential factor to achieve these objectives. In the transition from a community group to a political organization these discussions and decisions, in so far as objectives, strategy and organization become factors of primary importance.

The discussions in respect to the objectives are based on the fundamental premises of historical materialism, the eventual disappearance of capitalism, and the development of socialism as the predominant and fundamental method of production. But this transformation will not be gradual or purely economist. It demands conscious and organized action under the leadership of the working class, action which culminates with the implementation of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Assuming that we are in agreement in so far as the objectives, and considering that the consequences are in discussion, we still are confronted with two problems: first being the strategy of the proletarian revolution in the U.S. and the relationship between the national liberation struggles of the colonies and semi-colonies and the U.S. socialist revolution. Up to now we’ve ignored the studies of the historical development of the U.S. and till recently our level of work didn’t require such knowledge. There was no need for a national analysis (U.S.), rather the need was local or from the perspective of our nationality.

In relations to the second problem, we maintain, as we’ve previously expressed, that the struggles for national liberation presently being waged by the colonial and semi-colonial world are the principal struggles. We maintain that these colonies constitute the strength and reserves of the bourgeoisie in the imperialist nation further, that part of the wealth extracted out of our nations are used in “blackmailing” sectors of the northamerican working class. This implies that the development of the socialist revolution in the colonial and semi-colonial nations is of vital importance to the strategy toward-the revolution in the United States.

This link demands a vigorous analysis on our part in light of our experiences as a people living in the United States. What is the role of the Puerto Ricans in the U.S. in respect to Puerto Rico’s struggle for national liberation, the building of socialism and how should this be related to the socialist revolution in the U.S.? This is the central question that being discussed within our organization as part of our work.

We know that it is crucial to our objectives as a people that there be in the U.S. a revolutionary organization that fights for Puerto Rico’s national liberation and its people rights to self-determination. This is the duty of all revolutionary organizations in the U.S. not just the Puerto Ricans. In this sense the ideal is confronted by reality. With few exceptions this duty has been betrayed. If there are so many political organizations of a national form it is precisely because of this.

The third aspect to consider is the development of the organizational instrument necessary to achieve the set objectives. Should our most urgent task be to create a true Marxist-Leninist party in the U.S.? What is the role of the Puerto Ricans in the formation and development of such a party? And once again, what is the relationship of the struggle for national liberation and socialism in Puerto Rico? Present conditions demand these discussions.

The suspension of our publication, UNIDAD LATINA will be temporary. At this time we feel it is necessary to give our attention and resources to these questions which we think are fundamental.