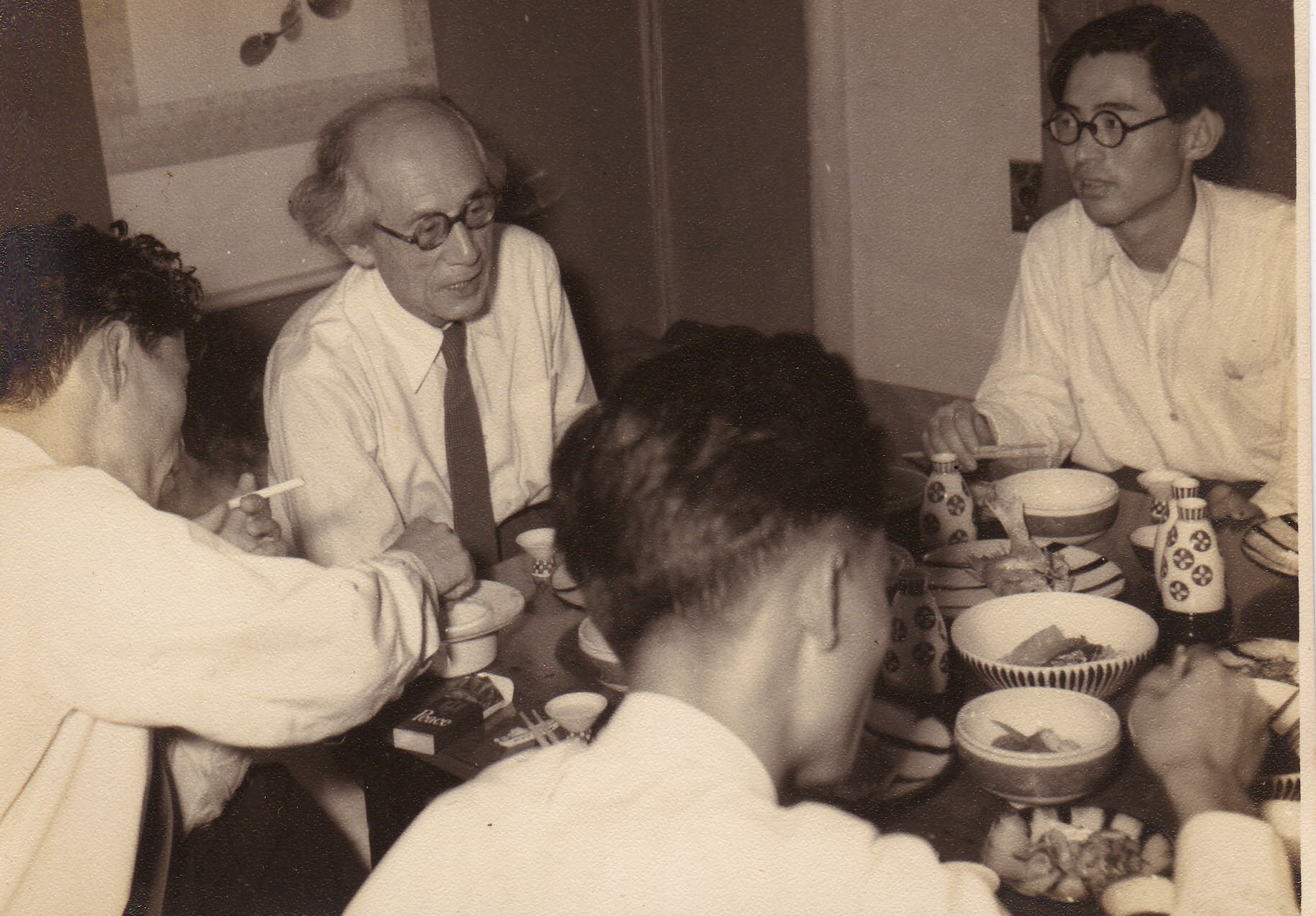

Samezō Kuruma (1957)

A quick look at Part 1 of Capital reveals that Chapter 1 is divided into four sections: “The Two Factors of the Commodity: Use-Value and Value (Substance of Value, Magnitude of Value”; “The Twofold Character of the Labor Represented in Commodities”; “The Value-Form, or Exchange-Value”; and “The Fetish-Character of the Commodity and its Secret.” This is followed by Chapter 2 and Chapter 3, respectively entitled “The Exchange Process” and “Money, or the Circulation of Commodities.” In looking at this structure, a number of questions arise.

First of all, the term “money” only first appears in a heading in Chapter 3, where Marx presents his theory of money, but even prior to that chapter money is analyzed. The term is first discussed in the theory of the value-form, appears again in the theory of fetish-character of the commodity, and is dealt with a third time in the theory of the exchange process. What is the exact relation between those three analyses of money and the theory of money presented in Chapter 3? That sort of question naturally arises, I think. It may seem obvious that Chapter 3 presents the fundamental theory of money, whereas Marx’s earlier analyses are an introduction of some sort to that theory, but we still need clarify the essential distinction between the two.

Second, assuming that the analyses of money prior to Chapter 3 are indeed introductory, what is the significance of each of the three theories just mentioned? A sense of frustration would be unavoidable, I think, unless we can elucidate this question.

A third point to consider is that, of the three theories thought to play an introductory role, the theory of the value-form and the theory of fetish-character are positioned as sections within Chapter 1 on the commodity, whereas the theory of the exchange process is positioned as the separate Chapter 2 placed parallel to the entire theory of the commodity. Moreover, that second chapter is placed on such equal footing despite being shorter than either of those two sections. We need to consider why this is the case.

These are the sorts of questions that will certainly arise if a person sets out to thoroughly understand the structure of Part 1 – or at least it was so in my case. In particular, the relation between the theory of the value-form and the theory of the exchange process is an issue that I struggled with over a very long period of time, starting shortly after reading Capital for the first time about thirty-five years ago. In each of those theories, the analysis seems to revolve around how money is generated; but the manner in which Marx carries out his analysis is completely different. Elucidating the essential difference between the two is actually quite difficult. Related to the difficulty is the fact that the theory of the value-form is one section within the chapter on the commodity, whereas the theory of the exchange process constitutes an independent chapter. Considering why this is the case was at the source of questions that I long struggled with.

When I first began studying Capital no detailed explanations were available in Japanese. Later I read Shihon-ron chukai (Commentary on Capital) by [the Soviet scholar] D.I. Rozenberg and Shihon-ron nyumon (An Introduction to Capital) by Hajime Kawakami, when those books were published; but neither provided what I felt were fully convincing arguments regarding the relation between the theory of the value-form and theory of the exchange process. After giving the matter considerable thought on my own, I eventually arrived at a view that seemed fundamentally correct. It was around that time, in 1947, that I participated in a series of monthly study meetings on Capital sponsored by the journal Hyōron, during which the question of the difference between the two theories was raised. The person leading that particular discussion explained the difference on the basis of the idea that the theory of the exchange process takes into consideration the role played by the commodity owner as a desiring agent (or the role played by the want of the commodity owner), whereas that role is abstracted from in the theory of the value-form. The discussion thus centered on whether it is possible to understand the value-form if the want of the commodity owner is abstracted from. The majority of the participants, myself included, sided with the view of that presenter, insisting that it is indeed possible. On the other side stood Kōzō Uno, who steadfastly maintained that the value-form cannot be understood if the want of commodity owner is set aside. Various arguments were raised by each side, but neither backed down. Ultimately the discussion broke down because of this disagreement, leaving us with no definitive answer regarding the essential difference between those two theories in Capital.

A transcript of the study meetings was published in the pages of Hyōron and later as a book. Carefully reading that transcript helped me to clarify my own ideas and thus arrive at a position that seemed fairly secure. I first presented my ideas in a series of articles entitled, “Theory of the Value-Form & the Theory of Exchange Process,” published in the journal Keizai shirin. The first article appeared in the January 1950 issue, followed by two others. I was in the process of writing a fourth article when I fell ill and that article was not completed.

Here I want to take up this topic again, drawing on the incomplete fourth article. I should note that the first three articles, which are grouped together in Part 2, respond to the three basic theoretical grounds of Uno’s view that the value-form cannot be understood if the want of the commodity owner is set aside. What remained to be done was to present my own positive views on the various questions that I raised earlier, particularly the distinction between the theory of the value-form and the theory of the exchange process. The three earlier articles, in responding to the theoretical basis of Uno’s argument, already naturally touched on the theory of the value-form because the issue of whether it is correct to abstract from the want of the commodity owner essentially concerns a methodological question determined according to the theoretical task of that theory. However, it is necessary to touch on the matter further here, as it is crucial to an understanding of the difference between the theory of the value-form and the theory of the exchange process.

In the theory of the value-form, Marx sets out to unravel the riddle of a commodity’s price (i.e., the riddle of the money-form), while at the same time untangling the riddle of money. The riddle of the money-form concerns the fact that the value of a commodity is generally expressed in the form of a certain quantity of a particular use-value: gold. The riddle of money concerns how, in that case, gold’s use-value – which is the element in opposition to its value – has general validity in its given state as value. Not only had no one prior to Marx solved those riddles, there was not even an awareness that they are in fact riddles. Marx became the first to thoroughly clarify these problems by raising the theoretical question in Capital pertaining to the value-form. Marx perceived, first of all, that the money-form is the developed value-form. This means that the riddle of the money-form is nothing more than an extension of the fundamental riddle of the value-form. By tracing the money-form to its source, thereby reducing it to its elemental form, which is the simple value-form, Marx locates the core of the riddle of the money-form and of money: the fact that a commodity expresses its own value in the use-value of another commodity that it equates to itself, thereby making the use-value of that other commodity the form of its own value. This is precisely the riddle of the value-form, which is the basis of the riddle of the money-form and the riddle of money. Without unraveling the first riddle, it is quite impossible to unravel the latter two; whereas those riddles are easily unraveled once the former has been elucidated.

The problem does not appear in such a simple shape, however, if the money-form is directly observed. This is because in the money-form the values of all commodities are only expressed in one particular commodity, gold, so that the riddle pushed to the forefront concerns the distinctive and mysterious character of gold based upon its privileged position. It is through the examination of the simple value-form that it first becomes apparent that the value of a commodity is expressed in the use-value of another commodity that is equated to it, and thus the fundamental problem regarding how this is possible comes to be posed in a pure form. Here we have the central question that Marx considers when analyzing the simple form of value. This is the reason he does not ponder why the coat, rather than some other commodity, is posited as the equivalent form of the linen. Granted, it is the action of the linen owner that posits the coat in the equivalent form, and this occurs because the owner wants a coat. But analyzing that factor is of no use when seeking to elucidate the question just posed. In fact, concentrating on it actually hinders the discovery of the answer by raising an unrelated question that blurs the problem at hand. This point becomes clear if we consider the fact that for the coat to be the value-form of the linen it must be equal to the linen, whereas for the owner of the linen to want the coat it must be different from the linen – the former is a relation of equality, the latter a relation of inequality. It is simply not possible to elucidate the how of a relation of equality by considering the why of positing different things. The question particular to the value-form is one that remains even after the role played by the individual want of the commodity owner has been clarified. It can only be posed as an independent problem by taking the value-equation, which is created by the commodity owner on the basis of his want, as a given. Naturally, a problem can only be thoroughly solved once it has been posed in a pure, independent form. Marx, in his theory of the value-form, analyzes the equation 20 yards of linen = 1 coat, without concerning himself with why the coat (rather than some other commodity) has been posited as the equivalent vis-a-vis the linen. He does this in order to pose the question of how the natural form of one commodity, a coat, becomes the form of value for the linen so that the value of linen can be expressed using the natural form of the coat. Marx thus uncovers the “detour” that constitutes the secret of value-expression, and upon that basis he became the first to thoroughly unravel the riddle of the money-form and the riddle of money.

In addition to the overview just provided regarding the theoretical task and method of the theory of the value-form (also discussed in Part 2), I want to offer an additional explanation for those who might find the overview too sketchy or difficult to understand or who may be unfamiliar with the “detour” of value-expression explained in detail in the first article of Part 2.

Generally speaking, the value of a commodity is always expressed using the use-value of another commodity that is posited as equal to it. In other words, it is expressed in the form of a thing. Developed further we arrive at the money-form, which is the form of price that is actually visible to us, where the values of all commodities are expressed in the form of a certain quantity of gold. The values of all commodities are expressed as gold of such-and-such yen. The term “yen” itself was originally the unit-name for the weight of a certain amount of gold qua money; under the Coinage Law in Japan it was the name given to 2 fun (.750g) of gold money. In other words, the term “yen” (in terms of gold of such-and-such yen) is nothing more than a quantity of gold expressed in a unit of weight that is solely used for money, replacing the usual weight unit names such as fun (.375g) or momme (3.75g) that were formerly used in Japan. It is through this quantity of gold that the value of a commodity – its value-character and its magnitude of value – is expressed in reality. Here we have the riddle of money. We see that the value of a commodity is expressed by a quantity of gold qua thing. But what makes this possible?

That is the question that Marx was the first to raise. And he goes on to brilliantly solve it. Marx perceives, first of all, that the expression of value in money (20 yards of linen = gold of '2; or 20 yards of linen = gold of such-and-such yen) is nothing more than the developed version of the simple value-form (20 yards of linen = 1 coat). Thus, the fundamental mystery of value-expression can be traced to that simple form of value. It is through his analysis of the simple value-form that Marx discovers the “detour” that constitutes the fundamental secret of value-expression. The detour concerns how, in the case of the equation “20 yards of linen = 1 coat,” in order for the value of linen to be expressed in the form of a coat, the coat itself must be the embodiment of value, which is to say the value-body [Wertkorper].[1] Otherwise, the quantity of the coat as a thing would not be able to express a magnitude of value. Because the coat is equated to the linen, its natural form in that given state is able to become something that expresses value. It becomes the embodiment of value. The coat thus attains the competence just mentioned, which is a definite economic form, thus coming to bear a social relation of production. The labor that makes the coat, of course, is itself specific concrete labor, not abstract labor. When the coat is equated to the linen, the tailoring labor that makes the coat is equated to the weaving labor that makes the linen, so that the coat-making labor is reduced to abstract human labor, which both types of labor have in common. Meanwhile, the coat is the embodiment of this abstract human labor. It takes on significance as the value-body, or embodiment of value, acquiring that formal determination. The linen, by positing the coat with that formal determination, expresses its own value in the body of the coat qua value-thing. Marx says that it is from this perspective that the riddle of value-expression can be unraveled for the first time. Here we need to pay special attention to the fact that the linen, in the value-expression 20 yards of linen = 1 coat, does not immediately turn itself into the form of value by saying that it is equal to the coat. Rather, the linen posits the coat as the form of value by saying that the coat is equal to itself, so that the natural form of the coat, in its given state, expresses value. The value of linen is thus expressed for the first time (in distinction from its use-value) in the natural form of a coat. This is what Marx calls the “detour” of value-expression. It is generally thought, and Marx himself concurred, that the theory of the value-form is the most difficult part of Capital. When Marx explains the detour of value-expression in the first German edition of Capital, he describes it as “the point where all the difficulties originate which hinder an understanding of the value-form” (Marx, 1976b, p. 21). Not only is the issue itself quite difficult to grasp, there has been a general lack of understanding regarding why it is necessary to ponder this issue at all (despite the explanations offered by Marx). The fact is, however, that the issue is at the core of the secret of value-expression. Without understanding the detour of value-expression, it is impossible to unravel the riddle of the money-form and the riddle of money; whereas those riddles can be easily grasped once the detour has been properly understood. The riddle of the money-form, as noted already, deals with the strangeness of a commodity’s value being generally expressed in the form of a certain quantity of gold. The riddle of money, meanwhile, involves the peculiarity in this case of the natural form of gold – its given bodily form – having general validity as value. This is the problem of the value-form posed in Capital, and it was by clarifying the detour of value-expression that Marx became the first to thoroughly solve it.

Next, I want to look at the theory of the exchange process in contrast to the theory of the value-form. I will begin by considering the characteristics of the theory of the exchange process in comparison to the entirety of Chapter 1 on the commodity. My reason for doing so is that the theory of the exchange process also constitutes an entire chapter and because I think it will be an easy-to-understand approach. We can find clues regarding those different chapters in passages from A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy) [hereafter: Contribution] and the first German edition of Capital. Those passages, which appear in both of Marx’s books prior to the analysis of the exchange process,[2] can be referred to as his “transition definition.” Marx offers one clue in the following passage from Contribution:

So far, the two aspects of the commodity – use-value and exchange-value – have been examined, but each time one-sidedly. The commodity as commodity however is the unity of use-value and exchange-value immediately; and at the same time it is a commodity only in relation to other commodities. The actual relation between commodities is their exchange process. (Marx, 1987, pp. 282-283)

Marx offers a similar description at the end of the analysis of the commodity in the first German edition of Capital, prior to examining the exchange process:

The commodity is an immediate unity of use-value and exchange-value, i.e., of two opposite moments. It is therefore an immediate contradiction. This contradiction must develop itself as soon as the commodity is not, as it has been so far, analytically considered (at one time from the viewpoint of use-value and at another from the viewpoint of exchange-value), but rather placed as a totality into an actual relation with other commodities. The actual relation of commodities with each other, however, is their exchange process. (Marx, 1976b, p. 40)

These descriptions make it clear that Marx – at least in Contribution and the first German edition of Capital – felt the theory of the exchange process differs essentially from the preceding analysis, with different observational dimensions.[3] Prior to that theory, the commodity is only examined analytically (and thus in a one-dimensional fashion); i.e., at times solely from the perspective of use-value and at other times solely from the perspective of exchange-value. That is not the case, however, in the theory of the exchange process, where a variety of commodities that are each the unity of use-value and value appear and are able as such to enter an actual relationship with each other in that process. I want to consider this point further, as it has significant bearing on the problem we are addressing.

Few would likely disagree that the commodity is considered analytically in Capital prior to the analysis of the exchange process (both in Section 1 and Section 2); and that the same can be said of the corresponding parts in the first German edition or Contribution which are not divided into those sections. But what about Section 3 where Marx analyzes the value-form? Can that section really be described as analytical? Or should it be said that both value and use-value play an indispensable role in the expression of value? Such questions seem likely but from my perspective they are based on a clear misunderstanding.

What is certain to begin with is that the theory of the value-form, not surprisingly, centers on the commodity’s form of value. The commodity, which is a unity of use-value and value, appears exclusively as value in the case of the value-form, which is a form distinct from the commodity’s direct existence as a use-value. It is natural in the theory of the value-form, therefore, to set aside the use-value of the commodity whose value-expression is being considered (i.e., the commodity in the relative form of value). Certainly, the commodity in its direct natural appearance, by nature, has the form of use-value. And then, in addition to that form, it comes to have the form of value, thereby acquiring the twofold form in which a commodity is actually manifested. The value-form of the commodity, therefore, is at the same time the “commodity-form of the product,” so that the elucidation of the value-form of the commodity is simultaneously the elucidation of the commodity-form of the product. Still, this does not by any means negate the analytical and one-dimensional nature of the theory of the value-form. That theory solely concerns the commodity’s form of value: the form in which a commodity expresses its value in distinction from its direct existence as use-value. The task particular to the theory of the value-form is to elucidate this value-form. The fact that the value-form of the commodity is also the commodity-form of the product (so that the elucidation of the value-form is the elucidation of the commodity-form of the product) means that the form of use-value is posited from the outset within the natural form of the commodity, and is therefore premised as such when the value-form is considered. This, to borrow Marx’s words, means:

The labor-product in its natural form brings the form of a use-value along with itself into the world. Thus there is only a need for the value-form in addition in order for it to possess the commodity-form. (Marx, 1976b, p. 61)

The theory of the value-form clarifies how a product, in order to appear as a commodity, obtains the form of value that it must have in addition to its inherent form as a use-value. If use-value can be said to play an indispensable role in the value-expression of a commodity, it is only the use-value of the commodity in the equivalent form, not the commodity in the relative form of value. A commodity’s value is clearly expressed using the use-value of another commodity that it is equivalent to it. Use-value, in its given state, thus becomes the form of value. This is precisely the relation that the theory of the value-form seeks to elucidate, its fundamental task; but that does not negate that the theory of the value-form is analytical and one-dimensional.

First of all, the use-value of the commodity in the equivalent form is not the use-value of the commodity whose value-expression is at issue, and is therefore not the use-value that is the oppositional factor to the value being expressed. In our familiar example, it is the linen’s value that is expressed, with the use-value of the coat playing a role in that expression of value. Even if it can be said that both value and use-value are being considered at the same time, it is the value of the linen and the use-value of the coat, not two oppositional factors within the same commodity. Thus, the commodity is not being analyzed as a totality consisting of both use-value and value. The issue revolves around the expression of the linen’s value and the perspective is solely that of value. The use-value of the coat is only manifested as the material for the value-expression of the linen. Moreover, as long as the coat is manifested as such, its use-value plays a role solely as the embodiment of abstract human labor, not in terms of its natural quality as a useful article of clothing.[4]

In the theory of the value-form, therefore, Marx solely considers the commodity from the perspective of value, setting aside its use-value. That is not the case in the theory of the exchange process. There, the process of exchange that is examined is first and foremost a process whereby commodities pass from the hands of the person for whom they are not use-values into the hands of the person for whom they are. This is the material content of the exchange process, and the process is unthinkable apart from this content. Marx thus describes the exchange process as, first of all, a process for the realization of the commodity as use-value. It should be noted, however, that the “realization of a commodity as use-value” is different from the “realization of use-value.” The “realization of use-value” concerns the attribute of being useful in satisfying a certain want, and thus involves actually putting a thing to use so as to realize its potential. This realization takes place within the process of consumption. In contrast, the “realization of a commodity as use-value” pertains to the exchange process. In the case of the latter, the use-value of the commodity is not merely use-value as such but a use-value with a certain social determinacy. It is not a use-value for the person who possesses it, but rather for another person. The commodity must therefore pass into the hands of that other person, and by so doing it first becomes truly useful as a use-value. This is what Marx is referring to by the “realization of a commodity as use-value” – which occurs in the exchange process rather than in the consumption process.

However, the exchange process of commodities is not limited to the process of realizing a commodity as use-value: it must at the same time be a process for realizing it as value. There are some, though, who have failed to understand what “realization as value” means, confusing it with “realization of value,” thus turning Marx’s theory of the exchange process into a complete muddle. The realization of value refers to the transformation of the value of a commodity – which had only existed in what might be called a “latent” state – into real value. In other words, the transformation of value into the shape of objectively valid value: money. This is something that clearly takes place in the process of selling. However, in the theory of the exchange process, where the question centers on the realization of the commodity as value, money has yet to be formed and the process of exchange has not yet been divided into the two processes of sale and purchase. From this point alone, it should be clear that the “realization of a commodity as value” differs from the “realization of a commodity’s value.” Regarding the former, Marx notes:

He [the commodity owner] desires to realize his commodity, as a value, in any other commodity of equal value that suits him, regardless of whether his own commodity has any use-value for the owner of the other commodity or not. (Marx, 1976a, p. 180)

As is clear from this passage, the realization of a commodity as value signifies that a commodity counts as something that actually has value, realizing its potential as value. As use-values, commodities come in an infinite variety, and for this reason they can be exchanged for each other; but as value (i.e., as the objectification of abstract human labor) commodities are indistinguishable and should be able to be replaced with any other commodity, at a given proportion. In order for a commodity owner’s product to be useful in that latter way, he produces commodities that are not use-values for himself. The owner, as the bearer of one part of the social division of labor, engages in the production of a particular commodity. But in order to do so the particular commodity produced must be exchangeable for a variety of commodities that are necessary to satisfy the owner’s various wants. As a simple use-value there is the likelihood that the commodity of a given owner will not be an object desired by the owners of the commodities that the owner himself wants. This would mean that exchange could not be carried out and that commodity owners would be unable to engage in the production of their own particular commodities without anxiety. This in turn would mean that commodity production itself would not be possible as one mode of the social division of labor. In order for commodity production to exist as a mode of the social division of labor, commodity producers must produce objects that are somehow socially desired. And to the extent that a commodity owner produces a socially desired object, he must at the same time be able to procure other commodities through exchange that are the product of the same amount of labor, regardless of whether his own commodity is an object desired by the owners of the particular commodities he wants or not. This is the original requirement of the commodity as value; which is to say, the requirement of the commodity as the objectification of labor that is indiscriminate, uniform and (in that form) social. And this is a requirement that must be realized in the process of exchange. The requirement of the commodity as value is naturally reflected in the consciousness of the commodity owner. As Marx notes in the passage just quoted, the commodity owner “desires to realize his commodity, as a value, in any other commodity of equal value that suits him, regardless of whether his own commodity has any use-value for the owner of the other commodity or not.”

The exchange process must thus be a process for the realization of the commodity as use-value, and at the same time a process for its realization as value. Yet the two realizations mutually presuppose and mutually exclude each other. Here a problem arises that is particular to the exchange process. The realization of a commodity as use-value occurs when it is handed over to another person, but the handing over of the commodity clearly presupposes the realization of the commodity as value. Meanwhile, the realization of the commodity as value is premised on its realization as use-value. If the commodity is not a use-value for the other person, it is not a value. However, the commodity is only first demonstrated to be a use-value for the other person when it is handed over as a use-value in the exchange process. This means that the commodity cannot provide itself with validity as value from the outset when it is exchanged. Not only is the realization of a commodity as use-value and as value a vicious circle of mutually presupposition, it is also a contradictory relation of mutual exclusion:

They [commodities] can be exchanged as use-values only in connection with particular wants. They are, however, exchangeable only as equivalents, and they are equivalents only as equal quantities of materialized labor-time, when their physical properties as use-values, and hence the relations of these commodities to specific wants, are entirely disregarded. A commodity functions as an exchange-value if it can freely take the place of a definite quantity of any other commodity, irrespective of whether or not it constitutes a use-value for the owner of the other commodity. But for the owner of the other commodity it becomes a commodity only in so far as it constitutes a use-value for him, and for the owner in whose hands it is it becomes an exchange-value only in so far as it is a commodity for the other owner. One and the same relation must therefore be simultaneously a relation of essentially equal commodities which differ only in magnitude, i.e., a relation which expresses their equality as materializations of universal labor-time, and at the same time it must be their relation as qualitatively different things, as distinct use-values for distinct wants, in short a relation which differentiates them as actual use-values. But equality and inequality thus posited are mutually exclusive. The result is not simply a vicious circle of problems, where the solution of one problem presupposes the solution of the other, but a whole complex of contradictory premises, since the fulfillment of one condition depends directly upon the fulfillment of its opposite. (Marx, 1987a, pp. 284-285)

The contradiction specific to the exchange process is manifested also as the collision between the various original wants of the commodity owner. That is, there is the want of the commodity owner to realize his commodity as value, which is the need to exchange it for a commodity of the same value regardless of whether his own product is a use-value for the owner of that particular commodity or not. At the same time, if the commodity owner is unable to exchange his own commodity for the other commodity that is a use-value for himself, he is also unable to hand over his own commodity. In other words, the owner wants his own commodity to count as value, but the other person might not recognize it as such. This situation is not limited to the owner of one particular commodity: every commodity owner is in this same position. As long as this is the case, exchange is blocked; and if the exchange process is at a standstill, commodity production also cannot be generally carried out.

This contradiction must somehow be mediated in order for commodity production to be generalized. What mediates it, needless to say, is money. With the appearance of money, exchange is carried out via the two processes of sale and purchase. The commodity owner no longer has to immediately seek to exchange his own commodity for the other commodities he wants. Instead, he can first exchange his commodity for money. This is the sale. In this process the commodity owner, instead of immediately seeking for his commodity to count as use-value, first hands it over as a use-value to transform it into money. By so doing, the labor expended on the production of the commodity is demonstrated to be socially useful labor. The commodity thus becomes the socially current form of value that is accepted throughout the commodity world; i.e., the commodity becomes money. When this happens, the commodity owner is able in the subsequent purchasing process to make this money count as value, exchanging it for the other commodity (or commodities) that he wants. This is objectively possible because his own commodity has become money. That was not the case prior to the appearance of money. Let us suppose that the owner’s commodity is linen, which he wants to exchange for a Bible. It would be very fortunate for him if there happened to be an owner of a Bible who is willing to exchange it for linen. But if the person who wants linen is the owner of wheat, while the Bible’s owner craves a bottle of whiskey, exchange could not be carried out. In that particular case, the owner of the linen has produced a commodity that is desired by the owner of wheat. This means that it is socially desired and that the labor objectified in the linen, which constitutes its value, is a certain quantity of human labor expended in a socially useful form. Despite this, if the linen cannot be exchanged for the commodity its owner is seeking (a Bible in this case), the linen cannot be realized as value. This contradiction is only mediated, in the manner noted earlier, with the appearance of money.

The exchange process constitutes a particular object of study as the place where the contradiction of the commodity as the immediate unity of use-value and value unfolds, and therefore as the place where the genesis of money becomes necessary to mediate that contradiction. This is precisely why Marx posits the theory of the exchange process as an independent chapter in Capital, placing it on the same level as Chapter 1. Yet some have argued that the contradiction of the exchange process is nothing more than the externalization of the contradiction inherent to the commodity between use-value and value at the stage of the value-form, so that it cannot be said that the contradiction first appears in the exchange process. I must say, however, that this view adheres to identity at the expense of distinction. Certainly, the analysis of the commodity is carried out through the analysis of the form in which the product appears as a commodity; but as long as the analysis of the form itself is at issue the commodity is not yet in a process of motion. We are not yet dealing, at this stage, with the process whereby the commodity as use-value passes into the hands of the commodity owner who wants it, nor are we considering the process whereby the commodity as value is actually transformed into another commodity. The realization of the commodity, as use-value or as value, has yet to be considered; therefore, the contradictory relationship between its realizations as that twofold entity has also not yet been examined. Moreover, the need for money to mediate this contradiction has not yet been raised at that point. The genesis of money is examined in the theory of the value-form, but the question revolves around how money is generated (not “through what”). In other words, the question centers on how gold, as a particular commodity, becomes the general equivalent, so that its natural form comes to count as value throughout the commodity world. It does not center on what makes this necessary or through what such a thing is formed. Not only is it possible to draw a distinction between these issues, it is only by actually setting them apart that we can thoroughly elucidate each as a distinct problem.

I do not mean to suggest, however, that the theory of the value-form and the theory of the exchange process are totally distinct from each other. There is in fact an extremely close organic relationship between the two, which I will consider. But we need to be aware of the significant difference between Capital and Contribution on this point. In Capital, prior to presenting his theory of the exchange process, Marx develops the theory of the value-form. In the theory of the exchange process, therefore, after Marx has traced the development of the contradiction of the commodity in that process and clarified the necessity for its mediation, when the question becomes what mediates the contradiction he can state that it was already clarified in the theory of the value-form. Marx pursues the issue further in Capital, after his examination of the relation of mutual presupposition and exclusion between the realization of the commodity as use-value and its realization as value, by posing the following problem:

Let us take a closer look. The owner of a commodity considers every other commodity as the particular equivalent of his own commodity, which makes his own commodity the general equivalent for all the others. But since every owner does the same thing, none of the commodities is general equivalent, and the commodities do not possess a general relative form of value in order to equate each other as values and compare the magnitudes of their values. Therefore they do not even confront each other as commodities, but as products or use-values. (Marx, 1976a, p. 180)

Marx is saying that as long as all of the commodity owners want their own commodities to count as value immediately, not only does this requirement confront the contradiction that unfolded at the previous stage, but also the formation of the general equivalent to mediate the contradiction becomes impossible. Thus, taking his argument one step further, Marx writes:

In their dilemma our commodity owners think like Faust: “In the beginning was the deed.” They have therefore already acted before thinking. The laws of the commodity nature [Warennatur] come to fruition in the natural instinct of the commodities owners. They can only relate their commodities to each other as values, and therefore as commodities, if they place them in a polar relationship with a third commodity that serves as the general equivalent. We concluded this from our analysis of the commodity. But only a social deed can turn a specific commodity into the general equivalent. The social action of all other commodities, therefore, excludes one specific commodity, in which all others represent their values. The natural form of this commodity thereby becomes the socially recognized equivalent form. Through the agency of the social process it becomes the specific social function of the excluded commodity to be the general equivalent. It thus becomes: money. (Marx, 1976a, pp. 180-181)

This passage clearly shows both the distinction and relation between the theory of the value-form and the theory of the exchange process. When Marx says that the commodity owners “can only relate their commodities to each other as values, and therefore as commodities, if they place them in a polar relationship with a third commodity that serves as the general equivalent,” and that we “concluded this from our analysis of the commodity,” he is clearly referring to the theory of the value-form or, more precisely, the examination of the general value-form. In Capital, as we have seen, prior to the theory of the exchange process the theory of the value-form is developed, where Marx elucidates how the general equivalent is formed and how the relation between commodities as value (and therefore as commodities) is mediated. Thus, in the theory of the exchange process, when Marx – having traced back the unfolding of the contradiction of the commodity within that process – arrives at the conclusion that, as long as the commodity owners immediately seek for their commodities to have count as value, ultimately no commodity can count as such, making it impossible for them to come into a relationship as commodities, he is then able to say that the path towards breaking through the deadlock was already elucidated in the theory of the value-form. However, even though that was clarified, it is the joint action (or “social deed”) of the commodity world that actually sets apart a particular commodity that becomes the general equivalent in reality. This joint action is made necessary by the deadlock of the unmediated exchange process and the contradictions that arise from that process which necessitate some sort of mediation. The task particular to the theory of the exchange process, along with tracing back the contradictions, is to analyze the necessity of the general equivalent for mediating the exchange process – i.e., the discussion of the necessity of the genesis of money – which is a task that falls outside of the realm of the theory of the value-form.

Incidentally, in the passage just quoted, Marx, in the literary style of expression he was fond of, writes:

In their dilemma our commodity owners think like Faust: “In the beginning was the deed.” They have therefore already acted before thinking. The laws of the commodity nature [Warennatur] come to fruition in the natural instinct of the commodities owners. (Marx, 1976a, p. 180)

Some have suggested that Marx in this passage is saying that the action of the commodity owners solves a problem that is theoretically unsolvable. On the basis of that view a unique explanation regarding the relationship between the theory of the value-form and the theory of the exchange process has been offered, which is then used to criticize Marx’s supposed theoretical bankruptcy. However, if we read a bit further on from the passage in question, it becomes clear that he is not arguing that an unsolvable theoretical problem is resolved through praxis. In fact, quite to the contrary, Marx notes that commodity owners act precisely in the manner elucidated by theory:

The laws of the commodity nature [Warennatur] come to fruition in the natural instinct of the commodities owners. They can only relate their commodities to each other as values, and therefore as commodities, if they place them in a polar relationship with a third commodity that serves as the general equivalent. We concluded this from our analysis of the commodity. (Marx, 1976a, p. 180)

Why, then, does Marx say that the commodity owners are somehow perplexed? Prior to the appearance of money the contradiction we have looked at must be confronted. But the commodity owners act in accordance with what theory has demarcated. In this way, they generate money, which is indispensable to the meditation of the contradiction. Marx describes the owners as having “already acted before thinking.” This is a wittier way, I think, of saying that money – like all other relations of commodity production – is something spontaneously generated, not the product of examination or some “discovery” as bourgeois economists often claim. There would be little point in using any witty turn of phrase if one ends up being misconstrued in the manner that Marx has. If he is to be blamed, it is not for leaving to praxis what his theory could not explain (and thus exposing his own theoretical impotence), but for not anticipating that he might be misconstrued in such a way.

My comments, however, pertain to Capital, because the matter is not presented in the same way in Contribution. In that earlier book, the theory of the value-form does not yet exist as an independent section or in terms of content (at least not as we find it in Capital). The same sorts of forms appear in Contribution (simple value-form, developed value-form, and general value-form), and they are developed in the same order. But when Marx analyzes the simple value-form in Capital he poses and elucidates the fundamental question of the value-form, whereas no such analysis exists in the earlier book. In Contribution, Marx simply writes:

The exchange-value of a commodity is not expressed in its own use-value. But as materialization [Vergegenstandlichung] of universal social labor-time, the use-value of one commodity is brought into relation with the use-values of other commodities. The exchange-value of one commodity thus manifests itself in the use-values of other commodities. (Marx, 1987a, p. 279)

In Contribution, crucial matters to be elucidated in the theory of the value-form are not dealt with at all, including the oppositional relationship between the relative value-form and the equivalent form, the detour of value-expression, and the particularities of the equivalent form. Without solving such fundamental problems, Marx discusses a development of form that is similar to the discussion in Capital in appearance only. Marx then examines what in Capital is called the “quantitative determinacy of the relative form of value,” followed by his analysis of the exchange process, where – upon sequentially unfolding the contradictions of that process – he poses the ultimate question that the issue comes down to:

It is through the alienation of its use-value, that is of its original form of existence, that every commodity has to acquire its corresponding existence as exchange-value. The commodity must therefore assume a double existence in the exchange process. On the other hand, its second existence as exchange-value itself can only be another commodity, because it is only commodities which confront one another in the exchange process. How does one represent a particular commodity directly as materialized universal labor-time, or – which amounts to the same thing – how does one give the individual labor-time materialized in a particular commodity directly a general character? (Marx, 1987a, pp. 286-287)

When the problem concerning the exchange process is ultimately posed by reducing it to the form above, Marx can respond in Capital by saying that the solution was already provided in the theory of the value-form. That is not possible in Contribution, however. In that earlier book, something similar to the theory of the value-form is developed prior to the analysis of the exchange process, but it does not answer the problem that is posed in the passage quoted above. After posing that problem in Contribution, and then introducing a series of equations for the developed value-form of linen, Marx offers the following response:

This is a theoretical statement since the commodity is merely regarded as a definite quantity of materialized universal labor-time. A particular commodity as a general equivalent is transformed from a pure abstraction into a social result of the exchange process, if one simply reverses the above series of equations. (Marx, 1987a, p. 287)

This can be said to occur by reversing the equations because the linen, which had been in the relative form, comes to be posited in the equivalent form. As for why this occurs when linen is placed in the equivalent form, that is a problem pertaining to the equivalent form in general, and therefore to the value-form in general, preceding not only the reversal of the equation but the developed value-form as well. It is thus a problem that must be solved when analyzing the simple form of value. In Contribution, however, there is no such examination. There is the passage above, where Marx explains the effect of the reversal of the equation, but that is merely confirmed as a fact and the theoretical elucidation is far less thorough than in Capital.

Further light can be shed on this issue by consulting letters Marx exchanged with Engels after sending him the revised proofs for the first German edition of Capital to solicit his opinions. Engels responded to Marx’s request in a letter dated June 16, 1867, noting his impressions regarding the analysis of the value-form. In that letter, after saying that divisions and headings should be added, Engels offers the following comment:

Compared with your earlier presentation [Contribution], the dialectic of the argument has been greatly sharpened, but with regard to the actual exposition there are a number of things I like better in the first version. (Marx, 1987b, p. 382)

Marx responded in a June 22 letter:

With regard to the development of the form of value, I have both followed and not followed your advice, thus striking a dialectical attitude in this matter, too. That is to say, (1) I have written an appendix in which I set out the same subject again as simply and as much in the manner of a school textbook as possible, and (2) I have divided each successive proposition into paragraphs etc., each with its own heading, as you advised. In the preface I then tell the “non-dialectical” reader to skip page x-y and instead read the appendix. It is not only the philistines that I have in mind here, but young people, etc., who are thirsting for knowledge. Anyway, the issue is crucial for the whole book. These gentry, the economists, have hitherto overlooked the extremely simple point that the form 20 yards of linen = 1 coat is but the undeveloped basis form of 20 yards of linen = gold of '2, and thus that the simplest form of a commodity, in which its value is not yet expressed as its relation to all other commodities but only as something differentiated from its own natural form, contains the whole secret of the money-form and thereby, in nuce, of all bourgeois forms of the product of labor. In my first presentation [Contribution], I avoided the difficulty of the development by providing an actual analysis of the expression of value only when it appears already developed and expressed in money. (Marx, 1987b, pp. 384-385)

Marx points out that in his earlier work he did “not actually analyz[e] the way value is expressed until it appears as its developed form, as expressed in money.” And we have noted that even this analysis of value-expression is certainly not carried out to a full extent in that book. In Capital, Marx does thoroughly examine this problem in a pure form, separate from the theory of the exchange process, as an independent problem that intrinsically belongs to the analysis of the commodity (along with the other theories that constitute Chapter 1).

My interpretation presented thus far regarding the relationship between the theory of the value-form and the theory of the exchange process is one that I arrived at after a long struggle, and I think that it grasps some fundamental points. However, one question I noted at the outset remains: Why was the “transition definition” that Marx placed between the theory of the value-form and the theory of the exchange process in the first German edition of Capital (and in Contribution) removed from the second edition of Capital? I am not so confident that I have the definitive answer to that question, however, because it is not something that can be answered on a purely theoretical basis. Moreover, Marx leaves us no comment anywhere related to this matter. What I can provide, then, is only conjecture.

One possibility is related to the changes Marx made to the theory of the value-form. Already we have looked at the nature of the theory of the value-form in Contribution, but in the main text of the first German edition of Capital as well the development of the value-form comes to an end with the rather peculiar form IV[5] instead of progressing to the money-form. In the case of form IV, what can be said of linen can also be said of any one of a multitude of commodities. Marx lists a number of equations expressing the developed value-form that include commodities such as coffee, tea, etc., in addition to linen, from which he deduces that “each of these equations read backwards gives coat, coffee, tea, etc. as general equivalent, therefore the expression of their value in coat, coffee, tea, etc. as the general relative form of value of all other commodities” (Marx, 1976b, p. 33). Marx also notes:

The general equivalent form always falls only on one commodity as opposed to all other commodities, but it falls on each commodity as opposed to all other commodities. If therefore each commodity opposes its own natural form to all other commodities as the general equivalent form, all commodities exclude all others from the general equivalent form, and therefore exclude themselves from the socially valid representation of their magnitudes of value. (Marx, 1976b, p. 33)

This is Marx’s examination of form IV and questions directly related to it in the main body of the first German edition of Capital. At first glance, though, it may seem that he is suggesting that the formation of a general equivalent is not possible; and since the formation of the general equivalent was already explained in form III, it may be difficult to see why such an analysis needs to be pursued. That is a view that has been advanced at times to criticize Marx, but from my perspective it is founded upon a clear misunderstanding. Marx is certainly not arguing that the formation of a general equivalent is impossible. Rather, he is indicating, from a more concrete perspective, the boundary between the earlier theory of the value-form and the theory of the exchange process, by means of reflecting on the outcome of the theory of the value-form developed up to that point and clarifying the limitations of an understanding based on abstraction from that earlier perspective. In the theory of the value-form, taking linen as his example, Marx clarifies how that commodity becomes the general equivalent through the process of a development of form. If linen has become the general equivalent, it must be thought to have passed through that process. However, as long as Marx is using the method of demonstrating the genesis of the general equivalent, any other commodity could pass through the same process (not just the linen); and to that extent any commodity could become the general equivalent. At the same time, however, no two commodities can become the general equivalent at the same time. If every single commodity simultaneously became the general equivalent, and developed into the specific relative value-form qua general equivalent, then “all commodities [would] exclude all others from the general equivalent form.” In short, the general equivalent must be limited to a specific commodity. Yet for this to occur, the operation of another factor – not mentioned in the analysis up to that point – is necessary for the general equivalent to adhere to one specific commodity. What is that factor? This is an issue that does not belong within Marx’s analysis of the commodity (which includes the theory of the value-form as one of its parts). This, at any rate, is my understanding of the gist of what Marx is saying in that passage quoted from the first German edition of Capital.[6]

The following passage from the theory of the exchange process (quoted earlier with regard to the difference and relation between the theory of the value-form and the exchange process) corresponds exactly to the passage above:

They [commodity owners] can only relate their commodities to each other as values, and therefore as commodities, if they place them in a polar relationship with a third commodity that serves as the general equivalent. We concluded this from our analysis of the commodity. But only a social deed can turn a specific commodity into the general equivalent. The social action of all other commodities, therefore, excludes one specific commodity, in which all others represent their values. The natural form of this commodity thereby becomes the socially recognized equivalent form. Through the agency of the social process it becomes the specific social function of the excluded commodity to be the general equivalent. It thus becomes: money. (Marx, 1976a, pp. 180-181)

We have already seen that Marx subsequently altered the content of form IV completely, inserting the money-form in its place. He also eliminated the description appended to form IV indicating the nature of abstraction in the theory of the value-form. I want to consider why Marx made such changes.

It seems likely that the money-form was inserted because the value-form reaches completion with the money-form and because it is the money-form that is posited in front of our eyes. It would have thus been insufficient had the value-form not advanced up to the money-form.[7] It also seems likely that Marx removed form IV and the description added to it because he thought that the previous limitations of the theory of the value-form had been superceded through the introduction of the money-form, rendering invalid the earlier reflection on the abstract character of the theory, because the advance from the general value-form to the money-form solely concerns the fact that “the form of direct and general exchangeability, in other words the general equivalent form, has now by social custom irrevocably become entwined with the specific bodily form of the commodity gold” (Marx. 1976b, p. 69).

The same situation may account for why Marx removed the “transition definition” from the second edition of Capital. If the advance from the general value-form to the money-form is simply a matter of the fact that “the form of direct and general exchangeability, in other words the general equivalent form, has now by social custom irrevocably become entwined once with the specific bodily form of the commodity gold” – and if it is true that “form D [the money-form] does not differ at all from form C [the general value-form] except that now instead of linen gold has assumed the general equivalent form” (Marx. 1976a, p. 162) – then the distinction between the two forms is not a difference in form, but rather concerns the real attributes of the general value-form. Hence, the question cannot be posed merely as an analysis of form. It can only posed for the first time on the premise of the real process that posits a specific commodity with the attribute of being the general value-form. This means that the transition definition, which includes the determination of the abstract character of the standpoint in Chapter 1, is no longer relevant. It is from this basic perspective that we can deduce why Marx removed the transition definition; or at least I can think of no other convincing explanation. Still, I do not necessarily think that introducing the money-form made it necessary for Marx to remove that passage. It is true that the issue regarding what specific commodity comes to acquire the attribute of the general equivalent form is quite different from the question of how the general equivalent itself is formed, as the latter can be examined abstractly (unlike the former). For the moment, though, we can set aside the conditions and reasons for the general equivalent form ultimately being affixed to gold[8] and instead treat the adhesion to gold as a fact, in order to examine the value-form solely from the aspect of form. This is indeed what Marx does in analyzing the money-form in the theory of the value-form.[9] Thus, even if the money-form is added, it is not necessarily imperative to also eliminate the transition definition. This is my reason for saying earlier that I am not convinced that I have arrived at the definitive answer.

The preceding has covered all of the points that I had planned to address with regard to the topic indicated in the title. However, there is still the issue noted at the outset regarding the fact that money is dealt with even prior to the theory of money proper in Chapter 3, not only in the theory of the value-form and the theory of the exchange process but also in the theory of the fetish-character in Section 4 of Chapter 1. Here I want to comment briefly on Section 4, beginning with the question of why the theory of the fetish-character is included in Chapter 1 on the commodity (along with Section 3 on the value-form) and how Section 4 differs from the other sections in that chapter (particularly Section 3).

We have seen that Marx examines the commodity in Chapter 1, which naturally involves an analysis of the commodity-form in which products appear. He elucidates, first of all, that the commodity is a twofold entity: both a use-value and an exchange-value. After noting this fact, however, Marx sets aside use-value because it does not express any social relation, despite being the “bearer” of social relations of production. Marx’s subsequent analysis focuses on exchange-value, whose simplest form is: x quantity of commodity A = y quantity of commodity B. Marx advances his analysis of that form by noting that the commodities on both sides of the equation have something in common even though they differ as use-values. He then elucidates what that thing in common is and what determines its magnitude. This is his inquiry in Section 1, which is entitled “The Two Factors of the Commodity”: Use-Value and Value (Substance of Value, Magnitude of Value). That first section already clarifies the distinction between the two elements (use-value and value) that make up the commodity, as well as the abstract character of the labor that forms value. In Section 2 (“The Twofold Character of the Labor Represented in Commodities”), Marx then clarifies the twofold character of the labor that produces a commodity, in terms of being an oppositional relationship between the labor that forms use-value and the labor that forms value. In this sense, Section 2 basically deepens the analysis from Section 1. The same equation is again analyzed in Section 3 (“The Value-Form, or Exchange-Value”), but from a different perspective. Whereas earlier he had examined the equation from the perspective of both commodities having something in common of the same magnitude, and then clarified what that is, in Section 3 Marx concentrates on how the commodity on each side of the equation plays a different role. He analyzes the fact that the commodity on the left has its value expressed in the use-value of the commodity on the right, clarifying how the value of a commodity is expressed in the use-value of another commodity and how value is ultimately expressed in a certain quantity of the money-commodity.

Marx also analyzes the equation in the theory of the fetish-character in Section 4 (or more specifically: “The Fetish-Character of the Commodity and its Secret”), but from a perspective that again differs. Having already pondered what is expressed in the equation in Section 1 and 2, and how it is expressed in Section 3, Marx turns his attention in Section 4 to the question of why:

Political Economy has indeed, however incompletely, analyzed value and its magnitude, and has uncovered the content concealed within these forms. But it has never once asked why this content takes that form, that is to say, why labor is expressed in value, and why the measurement of labor by its duration is expressed in the magnitude of the value of the product. (Marx, 1976a, p. 174)

Marx is raising a theoretical question not posed before. The question involves examining why the value of a commodity appears in the form of a quantity of another commodity that is equated to it (and ultimately in a quantity of the money-commodity gold that we encounter as “such-and-such” yen), rather than being directly expressed as a certain quantity of labor-time. In relation to money in particular, the theory of the fetish-character analyzes the why of money, whereas the theory of the value-form looks at the how of money.

In contrast to Section 4, the characteristics of the theory of the exchange process should be clear if we recall the difference between the theory of the value-form and the theory of the exchange process. Simply put, the investigation in Chapter 1 concerns the analysis of the commodity. This analysis is naturally carried out by examining the form in which products appear as commodities. However, as long as the problem is approached in this manner, the commodity has yet to enter a process of motion. The commodity is not in a process of motion as use-value, in terms of passing into the hands of another commodity owner who wants it; nor is it in a process of motion as value, in terms of being actually transformed into the commodity its owner wants. Marx has yet to examine the realization of the commodity as use-value or as value. Therefore, he has not yet analyzed the real contradiction that exists between the realizations qua those two elements; nor has he examined money as the mediator of that contradiction. All of those issues are first raised in the analysis of the exchange process. The genesis of money is discussed in the theory of the value-form, but the problem centers on “how” money is generated, not “through what.” In other words: How does a particular commodity (gold) become the general equivalent so as to count as value in its given natural form? The question does not concern through what money is made necessary and generated. These points have already basically been dealt with, but I want to add a further explanation here.

Marx analyzes the how of money in the theory of the value-form and the why of money in the theory of the fetish-character, whereas in the theory of the exchange process he examines the question of through what. Near the end of Chapter 2, as the final consideration of money prior to Chapter 3 (where he presents the theory of money proper), Marx writes: “The difficulty lies, not in comprehending that money is a commodity, but in discovering how, why, and through what [wie, warum, wodurch] a commodity is money” (Marx, 1976a, p. 186). Marx’s indication of these three difficulties clearly suggests that he managed to brilliantly overcome them, but no hint is provided regarding where this is carried out. My view is that Marx answered the questions how, why, and through what in Section 3 and 4 of Chapter 1 and in Chapter 2, respectively. In other words, the three problems are listed in the order that he solves them in Capital.

I should note, incidentally, that Marx does not pose the three problems as a sort of logical schema or in some frivolous manner. They are realistic problems. Without solving each one an adequate understanding of money is not possible. Indeed, earlier political economy slipped into a variety of errors by failing to solve these problems. One must begin with the realistic problem to be solved. Then the issue becomes how to solve the problem, in terms of where and how it should be examined. Therefore, it would be a waste of time, like casting pearls before swine, to present the solution to someone who has not yet grasped the problem. Yet some imagine that Marx is engaging in a frivolous discussion by posing those three questions, while others focus their attention on his statement as the penetration of some sort of Hegelian process of logic. Given the existence of such views, I think we can relish the following observations Marx made in a letter to Engels regarding the ideas of Ferdinand Lassalle:

Heraclitus, the Dark Philosopher, is quoted as saying in an attempt to elucidate the transformation of all things into their opposite: “Thus gold changeth into all things, and all things change into gold.” Here, Lassalle says, gold means money (c’est juste) and money is value. Thus the Ideal, Universality, the One (value), and things, the Real, Particularity, the Many. He makes use of this surprising insight to give, in a lengthy note, an earnest of his discoveries in the science of political economy. Every other word a howler, but set forth with remarkable pretentiousness. It is plain to me from this one note that, in his second grand opus, the fellow intends to expound political economy in the manner of Hegel. He will discover to his cost that it is one thing for a critique to take a science to the point at which it admits of a dialectical presentation, and quite another to apply an abstract, ready-made system of logic to vague presentiments of just such a system. (Marx, 1983a, pp. 260-261)

Finally, I want to touch very simply on the relationship between the three theories in Capital examined thus far and Chapter 3 (“Money, or the Circulation of Commodities”). Even if it is natural to view Chapter 3 as the fundamental theory of money, compared to the preceding introductory ideas, there is still the question of where to draw the essential distinction between the two. That particular question falls outside the framework of the present work, but I would like to simply note my view that money only first appears as the subject carrying out certain functions in Chapter 3. In contrast, the subject in the first two chapters is not money but the commodity. In those two chapters, money only appears as something necessary that the commodity brings forth to mediate its own contradiction; whereas in Chapter 3 the money thus created now appears as the subject that performs a number of functions. Here I think we have the essential difference, in very simple terms, between Chapter 3 and the first two chapters.

1. [Here and elsewhere Kuruma originally used the term “value-thing” (kachi-butsu; Wertding) rather than “value-body” (kachi-tai; Wertkorper); however, in his 1979 conversation with Teinosuke Otani, published as Part 1 of Kuruma’s book Kahei-ron (Theory of Money), he recognized that it “was an oversight” on his part to use the term “value-thing” in this case to refer to what should be called the “value-body” or “a thing that counts as a value-thing” (Kuruma, 1979, pp. 99-100). (That part of their conversation is not included in Part Two of this book.) In line with Kuruma’s comment, I have replaced “value-thing” with “value-body” when it is used inappropriately. – EMS]

2. In Contribution, those parts corresponding to Chapter 1 on the commodity and Chapter 2 on the exchange process in Capital are all included within Chapter 1, without any separating headings; but if we look at the actual content it is obvious which part in Contribution corresponds to the theory of the exchange process in Capital.

3. The passage just quoted does not appear in the subsequent editions of Capital; and later I will speculate as to why it was removed.

4. This is a point I make in the first article of Part 2 in relation to the question of abstracting from the want of the linen owner.

5. [I have used roman numerals (I, II, III and IV) to indicate the four forms of value in the first German edition of Capital and capital letters (A, B, C and D) to refer to the forms that appear in the second edition of Capital. – EMS]

6. After that passage, Marx goes on, in addressing the same fundamental point, to write:

“As one sees, the analysis of the commodity yields all essential determinations of the form of value. It yields the form of value itself, in its opposite moments, the general relative form of value, the general equivalent form, finally the never-ending series of simple relative value expressions, which first constitute a transitional phase in the development of the form of value, in order to eventually turn into the specific relative form of value of the general equivalent. However, the analysis of the commodity yielded these forms as forms of the commodity in general, which can therefore be taken on by every commodity – although in a polar manner, so that when commodity A finds itself in one form determination, then commodities B, C, etc. assume the other in relation to it.” (Marx, 1976b, pp. 33-34)

If it is the case that the discussion of form IV itself and issues related to it are a reflection on form III and that, in relation to the determination of the general equivalent posited there, the abstract character of the theory of the value-form is elucidated and the limitations of such cognition suggested, then I think it could be said that the passage above looks back on the entirety of the value-form developed up to that point and more generally clarifies its abstract character, while suggesting the limitations of that level of cognition.

7. Marx writes in the second edition of Capital:

“Every one knows, if he knows nothing else, that commodities have a value-form common to them all which presents a marked contrast to the varied bodily forms of the use-values – i.e., their money-form. Here, however, a task is set to us, which bourgeois economics never even tried to accomplish; namely, to trace the genesis of this money-form, i.e., to pursue the development of the expression of value contained in the value-relation of commodities, from its simplest, almost imperceptible shape, to the blinding money-form. When this is done, the riddle of money will also disappear at the same time.” (Marx, 1976a, p. 139)

As a matter of course, no description of this sort can be found in the first edition of Capital.

8. In the theory of the exchange process this issue is discussed in the following way:

“In the direct exchange of products, each commodity is a direct means of exchange to its owner, and an equivalent to those who do not possess it, although only in so far as it has use-value for them. At this stage, therefore, the articles exchanged do not acquire a value-form independent of their own use-value, or of the individual wants of the exchangers. The need for this form first develops with the increase in the number and variety of the commodities entering into the process of exchange. The problem and the means for its solution arise simultaneously. Commercial intercourse, in which the owners of commodities exchange and compare their own articles with various other articles, never takes place unless different kinds of commodities belonging to different owners are exchanged for, and equated as values with, one single further kind of commodity. This further commodity, by becoming the equivalent of various other commodities, directly acquires the form of a general or social equivalent, if only within narrow limits. The general equivalent form comes and goes with the momentary social contacts which call it into existence. It is transiently attached to this or that commodity in alternation. But with the development of exchange it fixes itself firmly and exclusively onto particular kinds of commodity, i.e., it crystallizes out into the money-form. The particular kind of commodity to which it sticks is at first a matter of accident. Nevertheless there are two circumstances which are by and large decisive. The money-form comes to be attached either to the most important articles of exchange from outside, which are in fact the primitive and spontaneous forms of manifestation of the exchange-value of local products, or to the object of utility which forms the chief element of indigenous alienable wealth, for example cattle. ... In the same proportion as exchange bursts its local bonds, and the value of commodities accordingly expands more and more into the material embodiment of human labor as such, in that proportion does the money-form become transferred to commodities which are by nature fitted to perform the social function of a general equivalent. Those commodities are the precious metals. The truth of the statement that ‘although gold and silver are not by nature money, money is by nature gold and silver,’ is shown by the congruence between the natural properties of gold and silver and the functions of money. ... Only a material whose every sample possesses the same uniform quality can be an adequate form of appearance of value, that is a material embodiment of abstract and therefore equal human labor. On the other hand, since the difference between the magnitudes of value is purely quantitative, the money commodity must be capable of purely quantitative differentiation, it must therefore be divisible at will, and it must also be possible to assemble it again from its component parts. Gold and silver possess these properties by nature.” (Marx, 1976a, pp. 182-184)

9. In carrying out his analysis, Marx notes:

“The specific kind of commodity with whose natural form the equivalent form is socially interwoven now becomes the money commodity, or serves as money. It becomes its specific social function, and consequently its social monopoly, to play the part of universal equivalent within the commodity world. Among the commodities which in form B figure as particular equivalents of the linen, and in form C express in common their relative values in linen, there is one in particular which has historically conquered this advantageous position: gold. If, then, in form C, we replace the linen with gold, we get ... “ (Marx, 1976a, p. 162)

At that point, Marx shows us form D (money-form), featuring an equation with an infinite number of commodities on the left-hand side and gold placed on the right, and then writes:

“Fundamental changes have taken place in the course of the transition from form A to form B, and from form B to form C. As against this, form D differs not at all from form C, except that gold instead of linen, gold has now assumed the general equivalent form. Gold is in form D what linen was in form C: the general equivalent. The advance consists only in that the form of direct and general exchangeability, in other words the general equivalent form, has now by social custom irrevocably become entwined with the specific bodily form of the commodity gold.” (Marx, 1976a, p. 162)

But the money-form does not stop at this alone. Immediately following the passage above, Marx adds:

“The simple relative expression of the value of some commodity, such as linen, in the commodity which already functions as the money commodity, such as gold, is the price form. The ‘price form’ of the linen is therefore: 20 yards of linen = 2 ounces of gold, or, if 2 ounces of gold when coined are £2, 20 yards of linen = £2.” (Marx, 1976a, p. 163)

Marx explains this point in greater detail in his discussion of the function of money as the measure of value in the Section 1 of Chapter 3: