MIA > Archive > P. Foot > Why you should be a socialist

|

‘We’re in the ditch, we’re in the ditch – |

|

Employers and television commentators have a word for the chaos into which we are being plunged. They call it ‘crisis’. ‘Britain is in a crisis’, they say. ‘This is the worst crisis since the 1930s.’

They talk of the crisis as though it were a feature of the weather; as though it had blown up suddenly over a calm sea. Politicians, economists and businessmen often use the language of meteorology to describe the crisis. For instance, Michael Foot, then Minister for Employment, told the 1975 Labour Party conference:

‘We are caught up in an economic typhoon’.

In the House of Commons in October 1976, Mr James Callaghan, Prime Minister and a former petty officer said: ‘We shall weather the storm and bring the ship home to port’.

These people tell us that the only answer is sacrifice. If we all make sacrifices, grin and bear it in the spirit of Dunkirk, then one day, perhaps, the typhoon will go away and the sun will come out once again.

Working people have been quick to respond to this call for sacrifice.

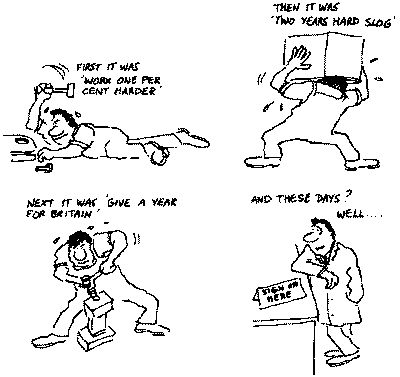

They have agreed to wage limits for 1975, 1976 and 1977 which have cut their standard of living for the first time since 1950. Pensioners and the poor have made sacrifices. Public service workers have in many places agreed to the run-down of their services and the loss of jobs. There were less strikes in 1976 than any other year since 1953. But now, after the first year of sacrifice, the crisis doesn’t seem to be going away at all. It’s intensifying, And as it intensifies, people who shouted for sacrifice last year call for more sacrifice this year. In 1964, the Tory Prime Minister Sir Alec Douglas Home called on British workers ‘to work one per cent harder’. They did – and it didn’t make any difference. In 1968, the Chancellor of the Exchequer Roy Jenkins called on British workers for ‘two years hard slog’. They gave it, and found themselves with a Tory government demanding more sacrifices in terms of legally-imposed wage limits.

In the summer of 1975, Prime Minister Harold Wilson called on British workers to ‘give a year for Britain’. They did, and now, with rising food prices, more unemployment and worse public services, they are asked to make sacrifices once again.

|

The first remarkable feature about these calls for sacrifice is that they scrupulously ignore the people who can most afford to make sacrifices. Consider, first, the people who make money out of interest – that is who make money out of having money in the first place.

In October 1976, the government raised the bank lending rate to 15 per cent. The newspapers howled about the misery this will undoubtedly bring to tens of thousands of people who are trying to buy the house they live in. But the newspapers didn’t point out so loudly that the decision meant a 20 per cent increase in the fortunes of moneylenders. Anyone who lends money benefited hugely from the wretchedness of the people who have to borrow money. The more money they had in banks or securities or local authorities, the more they reaped it in.

In 1975, three and a half thousand millions pounds was paid out to depositors in banks and building societies.

Another four and half thousand million pounds went in interest payments on money borrowed by other bodies, like local authorities. Denis Healey, Chancellor of the Exchequer, admitted in March 1976 that increased interest payments on government-borrowed money would account for almost all the £3,000 million which he was hoping to ‘save’ in public spending cuts. Yet, no one says to the moneylenders:

This is sacrifice year. This year we will not be paying out interest on money lent to the government or local authorities.

Or dividends: which is money made by having shares in companies. Last year one and a half thousand million pounds was paid in dividends on ordinary shares. In 1976, more than 70 per cent of all dividend payments rose. But no one says, ‘I’m sorry but the country is in a mess. There’ll be do dividends this year. We will take the money to save the school meals service, or keep the hospitals open.’ Not at all.

The dividends must be paid in full. Corporation tax which used to take a slice of company profits for the public purse has effectively been abolished over the past two years. Another two thousand million pounds have been ‘saved’ by companies in unpaid corporation tax.

Between 1971-2 and 1975-6, the taxable surplus of British companies rose from £11,124 million to £21,500 million. Yet the tax taken from these companies rose only by £487 million – from £1,500 million to £1,987 million. If tax had been collected at the 1971 rate, the government could have had an extra £2000 million to play around with. But, in times of sacrifice, they handed it back to the corporations.

In 1976, spending on advertising – that is on lies on television and in newspapers about the relative value of cereals, soap powders and so on – went up for the first time in history to more than a thousand million pounds. No one said: ‘We really must cut down on public lying, this year. We are in a crisis’.

Rich people seem able to afford just as much if not more of what they’ve been accustomed to. There’s an increase in waiting lists and in enrolment in private education – available because of high fees to only about three per cent of the population. In 1971, there were 408,394 children in public schools – by 1975 there were 421,658. British Airways report a sharp increase in the number of people who can afford a first class fare (a neat way of making up for high salary freezes). Lady Beaverbrook the wife of a newspaper proprietor can afford to charter an aeroplane to fly to Canada with her puppies. Yet there is no wealth tax, no freeze on luxury expenditure.

The truth is that we are not ‘all in it together’. We live in a society which is divided into classes. It is split from top to bottom between those who have property and wealth on the one hand yet produce none; and those who have none, yet produce it all.

The bare statistics of inequality in our society are almost incredible. The richest one per cent of our population, half a million people, own a quarter of all the personal wealth: yes a quarter of all the land, the factories, the houses, flats, offices, shares, securities, insurance policies, building society deposits, national savings certificates, household goods, furniture, kitchen utensils, fridges, washing machines, cars – a quarter of all personal wealth is owned by one per cent of the population. The top five per cent of the country own half the wealth, while the bottom eighty per cent, the mass of the population, own a mere 14 per cent. Everyone says that these figures are ‘getting better’. In fact, over the last year or two, they are not getting better. Between 1974 and 1975 there was a slight increase in the percentage of wealth owned by the very rich.

In Scotland, the figures are even worse. 0.1 per cent of the population, that’s 3,000 people, own a tenth of the entire country’s wealth, an average fortune per person of £270,000 a year. The ‘bottom’ eighty per cent of the people of Scotland own only five per cent of all the wealth! In 1959, they owned nearly fifteen per cent. That’s the ‘march of progress’.

The huge majority of the wealthy minority do not make their wealth through inventions, ideas or productive work of any kind. Many of them have their wealth through the strenuous business of being the sons and daughters of their fathers. Most of the others have made their wealth through interest or dividend or rent – all wealth which arises from work done by someone else.

Only three per cent of the people of this country get any money from dividends; less than a tenth get any income from interest.

The people who run the Stock Exchange and the banks are pretending ‘we are all shareholders now’. They point out that a great many shares are held by insurance companies and pension funds, and that the people who buy the insurance policies and who contribute to the pension funds are workers.

This is perhaps the most cynical of all the arguments used by the wealthy. Of course millions of workers do contribute to their firm’s pension funds, or buy insurance policies. But in doing so, they hand over their money to a small group of fund managers over whom they have no control, and who then proceed to gamble with their money on the Stock Exchange.

Civil service pensions, which are paid straight out of taxes, are larger for the pensioner and cheaper to run than pensions which come out of private pension funds. If the contributions were paid as extra tax, and the pensions paid out of tax, the pensions would be bigger and the contributions smaller.

The same goes for insurance policies. If there was one national insurance scheme which would safeguard people’s lives and personal belongings, millions would be saved in extravagant advertising, unnecessary competition or repetition. The private insurance companies do not increase people’s security. The pay-outs would be just as great, and the contributions less, in a single national scheme.

In other words, the argument that pension funds and insurance companies have ‘democratised’ the Stock Exchange is the opposite of the truth. The funds and insurance companies don’t spread economic power. They concentrate it.

They hand the control over enormous sums of workers’ money to unelected and unaccountable bureaucracies. They increase the inequality of society by taking funds from the less well off to make it easier to make money for nothing for the wealthy.

But the argument doesn’t stop at inequality. It’s not just that there are a handful of very rich people who make money for nothing living alongside poor and hungry people.

The point is that the rich parasites control society. They decide what’s produced, when it’s produced, how it’s produced. They decide what services are run. They decide who works where and for what rewards. They decide how many houses are built. They decide all these things according to whether or not they make a profit: that is whether or not they expand the wealth, privilege and power of the minority who already have it.

Look back at some of the examples in the last chapter about poverty and squalor in the middle of plenty and abundance. The explanation for all of them lies in profit.

Why do farmers sell their beef into cold storage rather than feed the hungry? Because the store pays higher prices, which the hungry can’t afford. Why do American farmers destroy food rather than ship it to Bangla Desh? Because they have to keep the price up to make a profit, and the price can be kept up by creating scarcity. Better a profit from a small sale than a loss from masses of hungry people eating. As John Pilger demonstrated in a television programme in September 1976, they are spending more in America on the promotion of a new moist lavatory paper than is needed to provide every peasant in the whole of South American with the money he needs to produce the food for the hungry round about him. Why? Because selling moist lavatory paper in America renders more profit than expanding agricultural production in the underdeveloped world.

How was Centre Point, a 29-storey office block in London, built and left empty for more than ten years, while there are 100,000 homeless in the same city? Because building houses for the poor is not profitable; but office values rise so fast that you can always make a profit from selling an office block, even if it’s always been empty!

Why do drug companies spend more on promotion than they spend on research? Why do the government plan to rip up 2000 miles of rail track and build 1,000 miles of motorway? Why is there tax relief on company cars to the tune of £600 million a year? Why are half the hotel bedrooms in London empty? Why did the taxpayers pay for the Concorde when never more than 0.5 per cent of taxpayers will ever be able to fly in it?

Because of profit, profit, profit. Because the privileges and unearned income of a minority are more important than the lives of the majority.

Go down to a Tory Party conference or listen in to a BBC Current Affairs programme any week and you will hear the argument for the profit system.

It is that there are only a few people in our society with initiative and enterprise. Most of these lucky people have initiative and enterprise because their fathers had it. Others demonstrate their initiative and enterprise by successfully competing in the business world. Unless we allow these people to have the maximum ‘incentive’, they won’t use their initiative and enterprise. Unless they are allowed to own all the factories, machinery, land and buildings, they won’t be able to use those machines and buildings in the most dynamic, enterprising way. Society will stagnate. We will go back to being a ‘banana republic’.

We must have more profits, continue the wealthy, because without profit there won’t be any investment and without investment there won’t be any jobs. And we, the wealthy, are the only people qualified to decide whether there should be any investment and what it should be.

We can test that argument by experience over the last four years. In 1973, there was a Tory Government and a boom. The government held wages down and allowed all forms of profit to rise. Enormous increases in rent, interest and profit were recorded. According to the capitalist arguments, those profits should have been converted into industrial investment and jobs. What happened?

Here’s the Investors Chronicle of 11 September, 1974.

‘In the summer of 1973, the government was allowing the amount of money for use in the country to expand rapidly in the hope that industry would use it to invest in new plant to produce more goods and earn more foreign exchange by exporting.

‘It did not work out that way, because industry was not confident that it could sell enough goods profitable enough to cover the money for new plant. So the extra money being pumped into the economy found other uses.

‘At first, some of it found its way into buying shares where it helped to force prices up. More important, vast amounts of money were being lent by the banking system to buy property. Since property is in limited supply, the main effect was to force prices sky-high’.

So much for the dynamoes, the men of initiative and enterprise! They turned out to be fringe bankers and property speculators. They stole the surplus of wealth from the workers and rolled around with it in the gutter of society.

In the end, of course, many of the banks and property companies which flourished in the great ‘free enterprise’ boom went bust. The heroes of the city editors suddenly became the ‘bad boys’. Jim Slater, the founder and former chairman of Slater Walker Securities, turned out to be what the socialists had called him all along: a share-dealer and asset-stripper who produced nothing whatever.

Indeed, his chief profitable venture was buying productive industry, sacking workers and selling off the assets. Yet this arch-marauder advised Prime Minister Heath. He was feted by all the capitalists in Europe. City editors wrote of Slater as the miraculous vindication of the argument of ‘freedom of movement’ for wealthy and powerful men.

Now he has been humbled and exposed, his former flatterers try to pretend that Slater was a ‘rotten apple in the barrel’. Like Sir Denys Lowson a former Lord Mayor of London who cheated other investors of £6 million; or the directors of Lonrho who amassed fortunes for themselves in tax havens; or lived rent-free in country mansions; or Prince Bernhard of Holland who stuffed himself with £1 million of bribes from the men of enterprise in the Lockheed Corporation; or Sir Hugh Fraser of Harrods and the Scottish National Party who saved himself a cool million by selling his own shares before the bad news about their real value emerged – these, all these, and many, many more, whine the spokesmen for capitalism, are ‘exceptions’.

They are not exceptions. They followed the central rule of the system: go for the biggest profit available. There was more profit in selling off the assets of one company to the other than there were in building new assets. Slater saw that and capitalised on it. He was, as he was acclaimed to be, a rulebook capitalist.

What happened in 1973 is being repeated even more catastrophically today. The entire economy is bent and twisted to provide more profit for the class who have the wealth. All the exhortations and policies of government are directed towards this aim. As a result, profits are expected to be £12,000 million – four thousand million more than last year. But investment in industry and service will go up at most by £800 million. Where will the other £3000 million go? The Financial Times gives a clue when it says that much of the rest is going in ‘speculative investment overseas’. Even more will simply be lent to the government at huge rates of interest. We can look forward to another round of property speculation or commodity speculation, or financial dealings. No doubt in two years, as we count the cost of another fruitless boom, there will be ‘inquiries’ into companies which today are being recommended as ‘good investments’.

The damage has been done however and will go on being done as long as freedom to use the resources of society is handed over to a handful of wealthy men with no social responsibility and over whom there is no social control.

The ‘men of initiative and dynamism’ waste the surplus wealth which they seize as though it were ‘theirs’. But their central crime is far worse than that.

They cause the economic crisis.

The employer, always wants to keep wages as low as possible. The lower the wages, the higher the profits. But low wages brings another set of problems to the employers. If wages are low, who is going to buy the goods which come out of the factory?

That’s the central problem for the capitalist. He can let wages rise as long as they don’t seriously interfere with his profits. But when wages do interfere with his profits, he prefers to close down his factory or sack large numbers of workers.

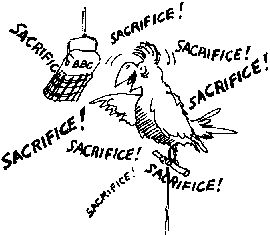

As a result, there’s even less wages around to buy goods from factories, so the slump careers on downwards. When wages have been forced down low enough, the capitalist starts investing again, and the wretched cycle starts again. But as investment and technology becomes more expensive, and each machine employs less men for more production, so each boom gets shallower and each slump deeper.

|

For a long time after the war, it looked as though the profit system had found a way out of its difficulties. For twenty-five years there was never as many as a million unemployed; and there was a gradual growth in production and the standard of living.

How did they do it? The answer is that ‘they’ didn’t ‘do’ anything. The enormous government spending on arms and military hardware ensured that millions of workers were being paid money for making goods which they didn’t have to buy.

The economist Keynes once argued that the only way to solve the central problem of the profit system was to pay large numbers of workers wages for digging holes in the ground and filling them in again. The trouble is that the people who control society will never agree to pay taxes for that. But they do agree to pay taxes for guns and tanks and bombs to fight off any other group or class which might want to come and take their wealth from them.

War spending, amounting to seven per cent of everything produced, was forced on the British ruling class after the war. It had never been anything like as high before in peacetime. And it helped to stabilise the economy and pay out money in wages for goods which workers were not buying.

But the same old devil re-emerged. Arms became more and more expensive. The state had to pay out increasingly huge sums to ‘maintain defences’, but less and less of this money went in wages, more and more of it in missile technology. So the pumping out of large sums into munitions workers’ pockets slackened, and, as it slackened, the old boom/slump cycle re-emerged.

At the bottom of each slump, unemployment was always higher than before – 700,000 in 1967, a million in 1972; a million and a half in 1976 – and who knows how many next time – or how soon next time will be?

During the ‘good old days’ of the 1950s and 1960s, the people with property were very confident. They allowed the growth of spending on social services. Similarly, they promoted ‘liberals’ into their political party: the Tory party. They believed it when they said they wanted a ‘free and easy society’. As long as it was easy to make profits, they liked things to be easy for everyone.

But when the profits became more difficult to make and when the society fell into crisis, the mask slipped. The liberals were packed off to the universities. Cuts were demanded in every form of public spending which did not produce instant profits. The unemployed were hounded as ‘scroungers’.

In the old days, when capitalism was made up of a number of small firms, all competing with one another, slump and crisis brought lower prices. But now prices are going up as fast as unemployment. The reason for this is the increasing power of a handful of mighty monopolies.

In 1910, the top hundred firms in Britain controlled only 15 percent of British manufacturing industry. By 1950, this had risen to only 20 per cent. Now they control half. By 1985 they will control two thirds.

By 1990, three quarters of all non-nationalised British industry will be controlled by 21 firms.

These firms have incalculable power. They produce different products and have interests all over the world. They can shift currency and machinery from different factories and plants to ‘fit in’ with strikes or government policy.

These giants are so strong and their control is so widespread, that they are not forced to cut prices in recession. They have given birth to a new monster, called STAGFLATION: stagnation in the economy, high unemployment – and prices rising at the same time.

The crisis, then, is their crisis. It is caused by the wealthy class which has the economic power. But that power does not stop at economics. It extends into every area of society.

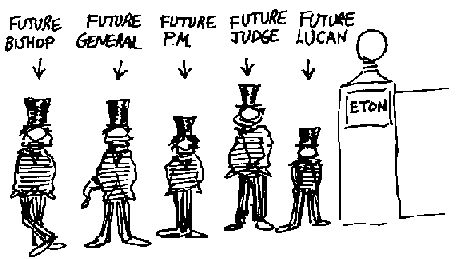

The armed forces are controlled by generals and officers who are never elected by anyone. They are selected for their breeding. Sir John Slessor, a former chief of the air staff, has proclaimed:

‘If we believe in the public school system, if we continue to claim its privileges, let us have the courage to admit that it does, and I believe always will, produce the great majority of the best leaders of men in Britain’.

More than three quarters of the top armed forces commanders in Britain were bred at public schools, and those that weren’t spent most of their time trying to prove that they were. The structure of power in the armed forces is strictly hierarchical. Warrant officers, petty officers, non-commissioned officers are appointed from above. All their responsibility is to the people above them.

It follows that obedience without question is the watchword of the armed forces. All discussion, especially political discussion, is frowned upon. Drill and ‘bull’, endless hours spent in prancing and polishing, are promoted in order, as one regimental sergeant major once put it, ‘to inspire a healthy respect for discipline’.

If the armed forces were a handful of infantry battalions and a few old battleships, this would not matter very much. But the armed forces have built themselves into a hugely powerful killing machine. After reading through the Pentagon papers, which were leaked from the American war machine and which told of the build-up to the American war in Vietnam, a New York Times reporter, Neil Sheehan, wrote:

‘The war machine, is a centralised state, for whom the enemy is not simply Communists but everything else, its own press, its own judiciary, its own congress, foreign and friendly governments – all these are potentially antagonistic ... It does not function necessarily for the benefit of the Republic but for the fulfilment of its own ends, its own perpetuation’.

Like Dr Frankenstein, capitalism has built a monster in its own image: a monster which no one can control.

The police are also controlled by members of the wealthy class, or by people who would like to be members of it. The first loyalty of police chiefs is a class loyalty. The Police force, like the army, is founded on the most ruthless hierarchy and discipline.

Alongside the police are various government intelligence agencies, which include the secret police. They, like the police, are a law unto themselves. Under cover of ‘the security of the state’ these men are entitled to open people’s letters and tap their telephones. Their chief activity is directed against all those who threaten class privilege and power. The section of the British Special Branch which deals with left-wing organisations is bigger than the fraud squad. The Special Patrol Group, which was set up mainly to counter demonstrations and other forms of left-wing activism, is stronger than many police units whose job is to put down crime.

The civil service, that is, the people who carry out the decisions of government, is controlled exclusively by wealthy men and women whose main loyalty is to their class. Leading civil servants are the same people as leading businessmen. Sir Edward Playfair, a top intelligence man in the civil service and Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Defence is 1961, left to become chairman of International Computers and Tabulators. Lord Allen, formerly permanent secretary at the Treasury, and head of the civil service, became chairman of the Midland Bank. Dame Evelyn Sharp, Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Housing, left for the boardroom of Bovis, a house building firm. There is a constant interchange between senior civil servants in the Post Office and the big telecommunications firms.

Secrets from this highly secretive bunch sometimes got out. In November 1976 it was revealed by Mr Fred Hirsch, a former official of the International Monetary Fund, that the IMF did not put conditions on loans to member countries.

The conditions were placed by the Treasuries of the borrowing countries. When Britain wanted to borrow, British Treasury officials always suggest a series of ‘conditions’ which they should attach to the loan. These usually include cuts in public spending, wage control – anything which would extract ‘sacrifice’ from a class of people which do not include senior civil servants.

No one can be a judge who hasn’t been a barrister. And no one can be a barrister without some form of ‘independent means’ and an initiation into a curious, spooky world of ‘dinners’, ‘inns of court’ and cranky uniforms. Eighty-six per cent of judges were educated at public school.

The ‘law’ which flows from these gentlemen is a law for the rich, made up by the rich.

There is no way of electing a judge, or of removing one once he has been appointed. Yet these rich gentlemen have the power to lay down the ‘common law’, and to interpret laws made by Parliament. The only appeal is to other judges, equally unaccountable and unrepresentative.

The class priorities of these gentlemen are not only obvious from their statements in court and their sentences, but by all the workings of the law.

There is a vast and powerful drug squad which spends most of its time tracking down people who are in possession of cannabis, a relatively harmless drug. Yet when a big drinks and drugs company, Distillers, marketed a sedative called thalidomide which led to the birth of hundreds of deformed babies, there was no prosecution.

Every conceivable effort is made to ensure that people on social security payments don’t claim too much money. Thousands of spies are hired every year to track down these culprits. In 1975 social security ‘frauds’ amounted to a loss to the government of £2 million. There were 15,350 prosecutions. In the same year, tax evasion was estimated to have lost the government £1000 million. There were 126 prosecutions for tax evasion.

‘The law must be enforced’ is a familiar slogan used by judges and their ilk. Yet an enormous body of law, passed to deal with recalcitrant employers, is either ignored or is enforced so slackly as to make the laws worthless.

There are laws which insist that employers preserve reasonable safety standards. But even after dreadful tragedies as at Aberfan, where more than 100 children died because of Coal Board incompetence, or at Flixborough where 30 workers died because of a big company’s negligence, there were no prosecutions. Even where there are prosecutions, the fines are derisory. When, in 1973, Marples Ridgway were found guilty of negligence which killed two bridge workers, they were fined £150.

A government campaign against low pay in the autumn of 1976 discovered 350 employers who were breaking the law by not paying the statutory minimum wage. Only three of these were prosecuted!

It is estimated that almost half office employers are breaking the Offices Shops and Railway Premises Bill, but almost none of them are prosecuted. There’s one law for the rich, and another for the rest of us.

When the Labour Government, after the war, nationalised a number of industries, people felt that control in those industries would shift towards the working people in them. That hope was very quickly dashed. Control of the nationalised industries was vested in boards which were appointed, not elected. Very quickly these boards turned the nationalised (industries into cheap suppliers and extravagant customers for private industries. Men like Lord Robens, who chaired the Coal Board from 1960 to 1970, behaved like business tycoons. By late 1976, several heads of nationalised industries, like former Shell boss Lord McFadzean (chairman of British Airways) and the chairman of the Central Electricity Generating Board, Sir Arthur Hawkins, were making speeches attacking the whole idea of ‘state interference in industry’. They want to run their state industries not for the state, but in the interests of their own class.

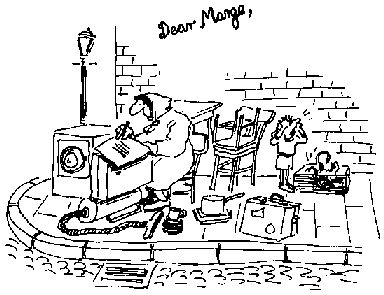

Ninety per cent of all national newspapers read in Britain are controlled by six companies, all of which have substantial interests in other parts of industry and finance. The newspapers, like commercial television, are kept in business solely through the advertising of big companies.

All editors and programme controllers in newspapers and television are appointed by their proprietor or company. The editors then appoint their own deputies, and heads of department. The result is a crawling hierarchy which ensures the maximum subservience to the proprietorial line. Local newspaper proprietors are, without exception, obsequious spokesmen for local private enterprise, friends and partners of local industrialists, bankers, Rotary Club chairmen. So the ‘news’ like the ‘law’ is not, as is pretended, neutral. It is ‘committed’ from top to bottom – on the side of the people with property and against the people without it.

In September 1976 a book was published called Bad News, which exposed the deep bias of both BBC and Independent Television News. As an example of what they found, the investigators quoted the dustmen’s strike in Glasgow in the winter of 1974/5. They monitored 14 news items on BBC about the strike, none of which gave a minute to the point of view of the strikers. On the day the book came out, the BBC News devoted nine minutes out of 26 to a report of a pending seamen’s strike. 15 seconds went to the seamen’s case. These are not exceptions. They are typical of a constant, unrelieved bias, even in so-called ‘objective’ programmes like The News, of a media which is controlled and martialled by a propertied class.

What are the fundamental ideas of the wealthy, which they pursue with such vigour in their newspapers, their television and their publishing houses?

They don’t of course argue anywhere that it’s right and proper that a few should own all the means of production and exploit the many. They arrive at that conclusion, of course, but by mythologies which sound much more attractive.

|

One of the most persistent of these mythologies is the notion of ‘the country’. How many times have you heard some gonk on television commending something ‘for the good of the country’ or ‘in the interests of the nation as a whole’.

The country of course never did anything; it has no ‘interests’. Somebody once said, My Country Right or Wrong, but no one ever pointed out that the country can’t be right or wrong. The country is a piece of territory.

If someone says, will you do this for poor people or oppressed people, will you do this because it’s fair or humane or decent – then that could make sense. But when they say, will you do this ‘for the country’, it makes no sense at all. It is drivel.

Usually television commentators urge us to do this or that (tighten our belts, usually) to defeat our competitors abroad. They say: ‘Britain has got to be competitive’ and they urge working people to make sacrifices to that end.

The same thing goes on in France and Germany and Japan and America. People are told to make sacrifices to make their country competitive so that they can beat their competitors abroad.

Supposing all the workers in the world responded to this amazing appeal. Suppose they all cut their wages, agreed to cuts in public spending, and tightened their belts. The result would be catastrophic: a world slump in production and an immediate drop in living standards for everyone as they tried to beat each other at the belt-tightening game.

Examples like that show what this ‘country’ business is all about. It’s a colourful substitute for ‘the wealthy class’.

They are the people who benefit from belt-tightening, from wars and from all the other nonsense which is urged on us in the name of patriotism.

Another idea which is consistently peddled is the disgusting notion that white men are superior to black men. This idea was enshrined by the men who went out from Britain in the last two centuries to rob and plunder countries overseas. These were the people, for instance, who wrecked the flourishing agriculture of Bengal in order to plant opium and sell it in China; the people who bought slaves from Africa and shipped them in conditions of indescribable cruelty to the West Indies to work the sugar and banana plantations. These upright English ‘gentlemen’ justified their own barbarism by explaining that black people in these countries were barbarians, and were extremely lucky to be employed, whipped and brutalised by the agents of white Christian civilisation.

The idea of white superiority was quietly suppressed by businessmen and their Tory government in the ‘good old days’ of the 1950s and 1960s.

Workers were needed to take the foulest jobs in Britain, because there was full employment and plenty of vacancies. Black workers were encouraged to come to Britain from India, Pakistan and the West Indies to take those jobs, and racialists who shouted ‘Keep Out the Blacks’ were discouraged. But as the crisis deepened, and as full employment vanished, so the racialists were let out of their cages. Led by a peculiarly neurotic hooligan called Enoch Powell, they started the chant: Stop The Blacks Coming, and Send the Blacks Home. Racialists of every persuasion were given space in newspapers and time on television to repeat the myths that Britain’s jobs shortage and housing shortage and hospital shortage would be improved if only the blacks went home.

It is all nonsense of course. There were many more unemployed in the 1930s when there were no black people, and almost no immigrants in Britain. The highest unemployment in the United Kingdom is in Derry and Strabane in Northern Ireland, where there has been no immigration for three centuries! If black people were sent home, so the taxes and rates they pay would be lost to the government. So there would be more sackings, less hospitals and less schools.

Black people in other words are workers like white people. They produce things, just as they consume them. They came because there was work for them – and if there is no work now, it is certainly no fault of theirs.

Racialism is not just nonsense. It is dangerous and pernicious poison. For black people in Britain today it means persecution by immigration officers, policemen and by racialist gangs. It means weaker trade union organisation as racial divisions are drawn into the geography of the factories.

We know what the end result of all racialism can be. We know what a Fascist government, brought to power by racialist anti-Jewish hysteria can mean. It means mass murder. It means the slaughter and torture of trade union activists and socialists of every description. That’s what happened in Germany, Austria, Italy and Spain in the 1930s. That was the high peak of capitalist crisis when the class with property found themselves with their backs to the wall. Then they used their ugliest weapon – racialism – to its extreme. Then the big industrialists and bankers paid Hitler to form a Fascist government.

The profit system and racial tyranny go happily hand in hand. In South Africa, where a brutal tyranny suppresses eighteen million blacks to maintain luxury and privileges for three million whites, the entire economy is subsidised and maintained by the same businessmen who prattle about freedom and democracy in Britain and America.

Racialism has one basic purpose: to identify a scapegoat for the economic and political crisis caused by the profit system.

That’s why, after twenty-five years in which British Fascists have been ignored and despised, they are now tolerated and in many cases encouraged by local newspapers and businessmen to come out of their cages and preach their ghastly creed.

Just as blacks are ‘better off’ in their own country, so women, according to the ideology of a bankrupt system, are ‘better off’ in the home.

The natural role for women, it is argued, is to complement men’s work by ‘looking after the home’ and ‘bringing up the children’. Cooking, cleaning, washing, tending to the needs of young children – all these are. assumed to be almost the sole prerogative of women.

It follows that women have neither the inclination nor the intelligence to ‘bother their little heads’ about a man’s world. The public affairs of men in particular, politics, trade unions, or whatever, are out of bounds. Instead, from the youngest age women are encouraged to live their lives through their menfolk.

Tens of millions of women’s magazines and women’s pages in daily newspapers are inspired by this remarkable proposition. The Lonelyhearts columnists rush to the assistance of their women correspondents who are usually desperate about this or that ‘problem’ which arises in their relationship. These columnists often provide comfort in some sad household. But their starting point is that women’s personal relationships are the single dominating influence of their lives.

There is a model to which every family is urged to aspire: the man working hard and without complaint; the woman cheerfully busying herself about the home; the children ‘brought up’ in decent subservience to the Queen and the master of the household. The model is presented in terms of ‘love’ and ‘happiness’. But the attempts of millions of people to aspire to the model tend to lead them in the opposite direction. The separation of the man’s life ‘in the outside world’ from the woman’s life in the home leads to a collapse of respect and common interest – and inevitably a collapse of love. When love for children is restricted to love of your own children, then the love soon degenerates into irritation, unfulfilled aspirations and jealousy. The whole model leads to a vast reservoir of frustration and humiliation.

The ideas behind the model, of course, are so much rubbish. Women are plainly not more suited to cooking, cleaning, washing and ironing than are men. Women are not necessarily more suited or more expert at looking after young children than are men. Women plainly are just as, if not more, interested or capable of being interested in what goes on in the world as are men. Women are just as competent, efficient, practical, conscientious workers as men. Women get bored by isolation as much as men. Love and happiness between men and women do not grow from separating their functions into outside worker and domestic slave. Affection and respect between adults and children do not grow by shutting families off from one another in little boxes, so that everyone else’s child becomes an object of jealousy and one’s own becomes a mass of unfulfilled aspirations.

A class which depends for its existence on discipline, order and hierarchy needs to ensure that these things are installed in every corner of society. The ‘natural law’ which promotes big potentates in the factory or office, also promotes little potentates in the home. If women can be made to live through the aspirations of others, they will never have any independent aspirations themselves. They will stop thinking for themselves and acting for themselves.

And so we return to the basic message: the central idea of the profit system which supports all the others.

It is that only a few are blessed with the qualities necessary for leadership and for making decisions.

The majority, the masses, by the same token, are incapable of making decisions. They are still, as the old Tory orator Burke once described them, ‘the swinish multitude’. Their best course is to do what they are told and accept what they are given (or what is taken away from them) without complaint. Obsequiousness and acquiescence are the paramount virtues of working class people in a capitalist dreamland.

Like all the other damnable doctrines circulated as ‘orthodox’ in our society, this view has only one purpose: to preserve wealth, luxury and privilege in the hands of a minority. The entrepreneurs and the men with ‘dynamism and initiative’ are far less capable of taking decisions than any shop stewards’ committee, or for that matter any council of unemployed black workers in Brixton.

The wealthy class have brought society again and again to the rim of hell. They have fought monstrous wars against each other, in which millions of workers have perished. They have developed production only to satisfy their seemingly endless lust for wealth and power; they have squandered the surplus which they have appropriated in such a way as to ensure catastrophic economic crisis – and now they have the nerve to insist on more sacrifice from the multitude whom they exploit.

They are the garbage of society and the stink will continue until they are cleared away.

|

Last updated on 7.1.2005